🎭Sanxingdui Mask and the Lost Civilization of Shu in Ancient China

The Masks That Time Forgot

🪨 The Earth Opens – A Discovery Beneath Sichuan's Soil

In the summer of 1929, the course of Chinese archaeology was forever altered when a humble farmer named Yan Daocheng, while digging an irrigation trench near the small village of Sanxingdui in Guanghan, Sichuan Province, struck something solid just beneath the surface. What emerged was not stone or wood but smooth, polished jade—an intricately carved object unlike anything local villagers had seen. The discovery passed quietly at first, filed away as a strange curiosity. But it hinted at something enormous and long-buried under the rolling plains of western China.

In the years that followed, more artifacts were occasionally turned up by villagers and construction workers: jade blades, peculiar pottery, fragments of bronze. But it wasn’t until the 1980s that a full archaeological team began serious excavation. In 1986, two sacrificial pits were uncovered that completely redefined the understanding of ancient Chinese history. Inside were thousands of objects—smashed, burned, and buried in layers—among them massive bronze masks, golden ornaments, ceremonial tools, and trees of bronze unlike anything ever seen.

These finds challenged the long-held assumption that Chinese civilization had developed only along the Yellow River. Sanxingdui proved that another advanced and powerful culture had flourished in complete parallel, far from the established Shang Dynasty. Located in the rich Chengdu Plain, Sanxingdui had been a sprawling Bronze Age city whose people left no writing, no known burial sites, and few traces of their everyday lives—but who buried artistic and ritual artifacts on a scale so vast and strange that modern scholars still struggle to explain them.

👁️ Masks of Bronze and Gold – Faces of Another World

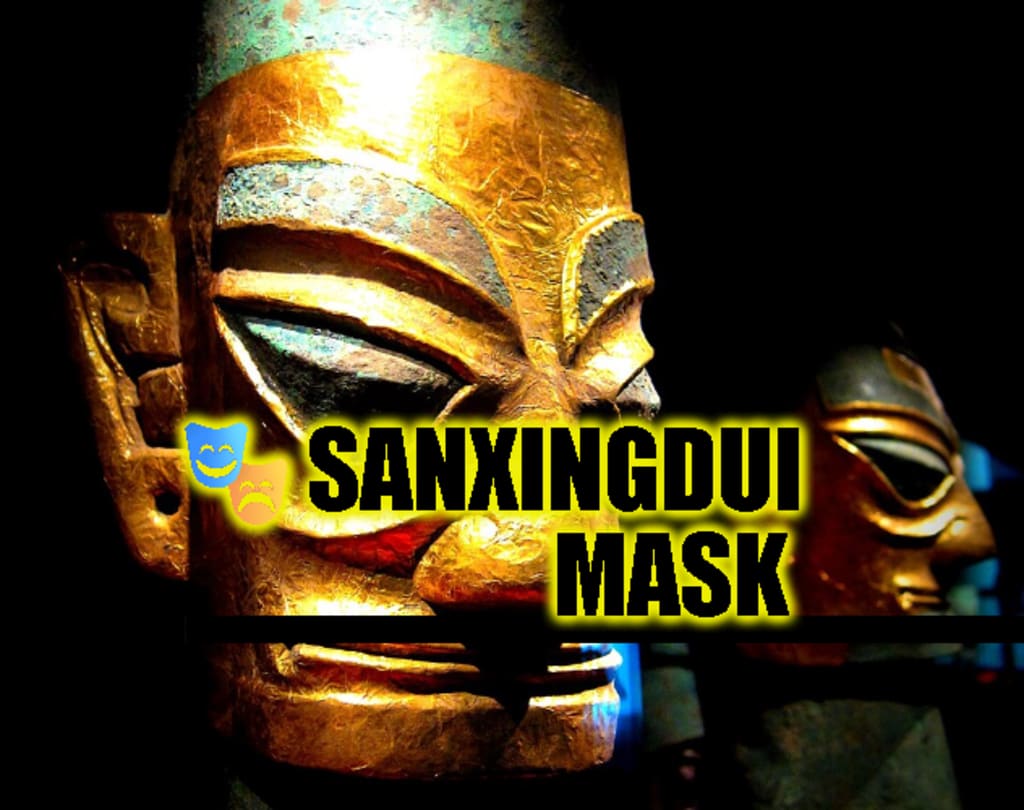

The most visually arresting artifacts uncovered at Sanxingdui are the massive bronze and gold masks, some of which are life-sized while others are larger than any human head. These are not functional masks designed to be worn. Many are over a meter wide, with heavy ornamentation, elongated eyes, and stylized ears that stretch outward like wings. They are rigid, ceremonial objects—designed to be mounted, displayed, or placed in sacred spaces, not worn by human hands.

The faces depicted have exaggerated features: protruding, almond-shaped eyes that sometimes extend like tubes; high-arched eyebrows; sharp, flat noses; and tight, expressionless lips. The style is highly abstract—geometric and symbolic rather than naturalistic. Some of the masks include hints of animal traits: horned foreheads, bulging frog-like eyes, bird beaks, or tusks. These may have represented gods, spirits, shamans, or ancestors who had crossed over into a divine or transformed state.

One of the most famous pieces is a bronze human head with huge protruding eyes and gold foil covering the face, a sculpture that looks distinctly alien to modern observers. Another is a massive bronze mask with spiraling dragon horns and a solemn, almost robotic expression. These are not decorative art—they are deeply spiritual objects designed to command presence, to invoke awe and fear. The scale and craftsmanship suggest they were used in grand rituals, perhaps displayed in temples or mounted on wooden totems towering above crowds.

Some masks are fully covered in hammered gold foil—thin sheets meticulously applied to create a gleaming, divine finish. Despite being buried for over 3,000 years, many of these gold layers remain intact. Others are decorated with painted pigments, including red cinnabar and black mineral paints, indicating vibrant original coloration. The style has no parallel in the art of the Shang Dynasty, which at the time was producing more conservative bronze vessels and ritual tools. The Sanxingdui masks appear to belong to a completely separate symbolic system.

The most significant archaeological features of Sanxingdui are the sacrificial pits—deep, layered shafts filled with shattered artifacts. In 1986, two such pits were excavated, designated Pits 1 and 2. These pits contained thousands of objects—bronze sculptures, ivory tusks, ceremonial jade blades, gold artifacts, and the famous bronze masks. However, what made these finds particularly intriguing was that nearly every object had been deliberately destroyed before being buried.

Broken axes, smashed statues, dismembered bronze trees—everything had been fractured, burned, or deconstructed. Elephant tusks had been snapped in half and blackened with fire. Wooden items had long decayed, but their ash traces remained. This was not careless destruction. It was systematic, ritualistic, and symbolic. These were sacred offerings—deactivated through destruction before being entombed in the earth.

This type of large-scale ritual deposit suggests a highly developed belief system. The pits may have been created to mark important spiritual events: the death of a king, a celestial omen, the founding of a temple, or to appease natural disasters. The presence of so many precious materials—gold, jade, ivory, and bronze—indicates that the sacrifices were made by an elite society with substantial resources and religious organization.

In 2019, further excavations began at the site, using modern techniques like ground-penetrating radar, drone mapping, and 3D scanning. This effort revealed six additional sacrificial pits, designated Pits 3 through 8. Each contained even more elaborate artifacts: bronze altars, dragon-headed scepters, ivory carvings, and fantastical tree-shaped sculptures. Over 10,000 new objects were unearthed in this phase, solidifying Sanxingdui's position as one of the most artifact-rich archaeological sites in China.

🐉 The Enigma of the Shu – A Civilization Without Words

Despite the monumental artistry and advanced metallurgy on display at Sanxingdui, the civilization behind it—often identified as the ancient kingdom of Shu—remains largely anonymous in the historical record. No written documents have been discovered at the site. No script has survived. The Shu left no royal tombs, no palaces, and no named leaders preserved in inscriptions. Everything we know comes from later Chinese texts and the artifacts themselves.

Some of these later texts mention a mythical figure named Cancong, said to be the first king of Shu. He is described as having large, protruding eyes—perhaps a symbolic ancestor represented in the wide-eyed bronze masks. Another legendary figure, King Yufu, was said to have had bird-like features. These descriptions loosely match the artistic motifs seen at Sanxingdui, but they were written centuries after the civilization had vanished.

The artifacts suggest a complex religious system, likely animistic or shamanic in nature. Bronze statues of kneeling figures—lifesize in some cases—appear to represent priests or shamans in ceremonial robes, offering objects to unseen forces. Many of these figures are highly stylized, with bird motifs, sun emblems, and serpentine forms suggesting totemic beliefs. Birds, in particular, dominate the art. Some sculptures show long-beaked birds standing on sacred trees; others show humanoid-bird hybrids in worshipful poses.

Bronze trees discovered at the site are particularly striking. One stands over four meters tall and includes birds, fruit, dragons, and coiled branches. These may represent cosmic trees, serving as a link between heaven and earth—a concept found in many early cultures. Their presence suggests a theology of vertical connection: underworld, earth, and sky united in ritual practice.

⚒️Masters of Bronze and Silk – An Industrial Wonder

The technical skill behind the artifacts at Sanxingdui is extraordinary. The bronzes were not crude castings. They were engineered using complex piece-mold casting techniques, allowing for thin walls, hollow eyes, protruding features, and delicate details. The scale of the largest sculptures—some weighing over 100 kilograms—demonstrates not only artistic ambition but logistical planning, including furnaces, molds, and coordinated teams of craftsmen.

Bronze production was tightly controlled. Artisans used carefully calibrated ratios of copper, tin, and lead to achieve the desired hardness, durability, and color. Some masks were cast in multiple pieces and joined seamlessly. Others included hinges or slots where additional elements—possibly wooden, textile, or leather—could be attached. Though few organic materials survive, traces of silk and lacquer suggest a complex culture of decoration and presentation.

Ivory tusks found in the pits indicate trade networks stretching far beyond the Chengdu Basin, likely involving exchange with Yunnan, Southeast Asia, or even regions further west. The presence of jade objects—many in styles foreign to the Sichuan area—suggests that Sanxingdui was not isolated but participated in a vast Bronze Age world.

These were not primitive metallurgists. They were engineers, artists, spiritual leaders, and traders. And they worked on a monumental scale. The city of Sanxingdui itself was surrounded by massive rammed-earth walls, with residential areas, production centers, and ritual zones spread over several square kilometers. Based on artifact density and infrastructure, archaeologists believe the population may have reached tens of thousands.

🌀Disappearance Without Explanation

By approximately 1150 BCE, all activity at Sanxingdui abruptly ceased. The sacrificial pits were no longer filled. The site’s buildings decayed. The artistic tradition vanished. And there is no record of invasion, war, or gradual decline. The people simply left.

One theory holds that a catastrophic flood changed the course of the nearby Min and Yazi Rivers, which would have disrupted agriculture and rendered the city unsustainable. Another possibility is that the political or religious leadership shifted, and a new capital was established elsewhere. Some believe environmental degradation, seismic activity, or disease may have played a role.

The most compelling evidence suggests that the culture didn’t die—it moved. Just 40 kilometers to the southwest, another site called Jinsha rose to prominence a century later. Many of the same motifs—bird symbols, jade, ivory, and bronze masks—appear at Jinsha, though in a more simplified form. It is possible that Jinsha represents the spiritual successor to Sanxingdui, reestablishing Shu culture in a new location after catastrophe.

Today, Sanxingdui is one of China’s most celebrated archaeological sites, yet it remains a mystery. The culture it reveals was vast, sophisticated, and utterly distinct. It challenges the traditional view of early Chinese civilization as a single river-born lineage. Instead, it shows that the story of ancient China was one of multiple cultures, developing independently, sometimes in parallel, sometimes in silence.

The masks of Sanxingdui—strange, elegant, powerful—remain iconic symbols of this lost civilization. They are not alien, as some have fancifully claimed, but deeply human. They reflect a spiritual imagination, a ritualistic worldview, and an aesthetic sensibility unlike anything else in ancient art.

What remains is a silent language of bronze and gold. Eyes that stare into eternity. Masks that never speak. And a people who once walked the earth with birds on their altars, fire in their furnaces, and gods in their trees.

Their names may be lost. But their faces remain.

About the Creator

Kek Viktor

I like the metal music I like the good food and the history...

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.