🏰Petra: The Lost Rose City of the Nabateans

🌵The Ancient City Carved from Desert Stone

🏰Petra: The Lost Rose City of the Nabateans

🌵The Ancient City Carved from Desert Stone

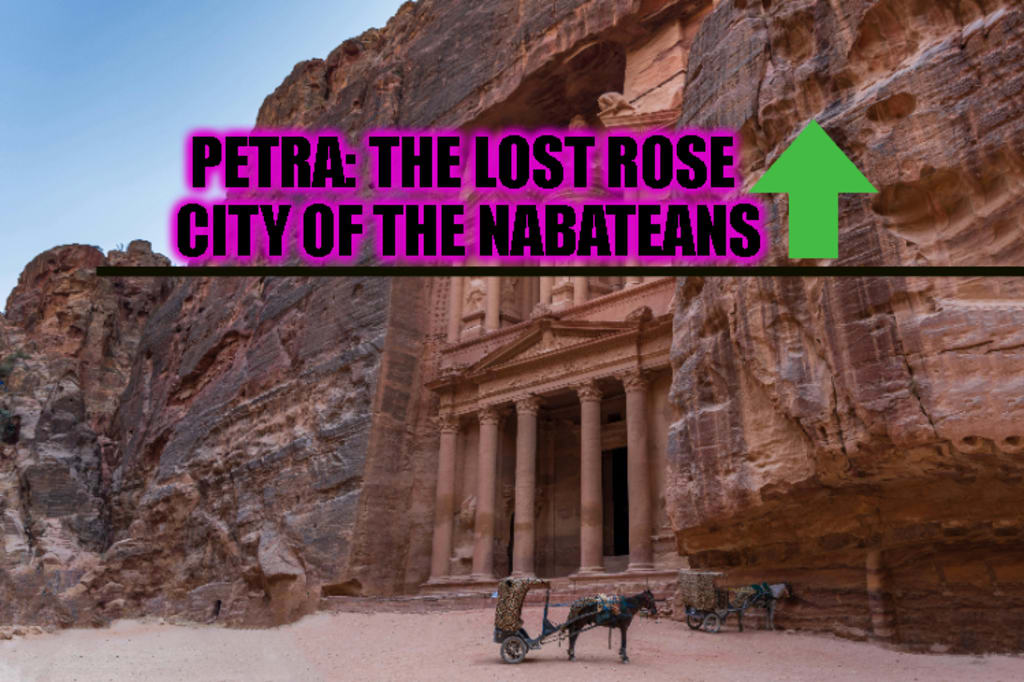

If you ever find yourself in southern Jordan, standing at the mouth of a narrow canyon while the desert wind swirls red dust around your feet, you might have the sense that you’re on the edge of something extraordinary. And you’d be right. Just beyond that winding chasm lies Petra—a city carved straight into the rose-colored cliffs, a place that once bustled with life and now sits in silent, sun-baked grandeur. Petra isn’t just a monument to the past. It’s a labyrinth of stories, secrets, and stone, and its legacy is still unfolding.

Beginnings in the Desert: The Nabateans’ Rise

Petra’s story begins with the Nabateans, a people whose origins are still a bit of a mystery to historians. What we do know is that by the 4th century BCE, the Nabateans were moving into the region that would become their kingdom’s heartland. They weren’t empire-builders in the classical sense—they didn’t conquer huge swathes of land with armies. Instead, they were traders, masters of navigating the harsh Arabian deserts, and experts at finding and guarding water in places where it seemed impossible.

The Nabateans realized early on that Petra’s location was perfect. It sat at the crossroads of several major trade routes connecting Arabia, Egypt, Syria, and the Mediterranean. Frankincense, myrrh, spices, silk, gold, and precious stones all passed through this landscape, and the Nabateans became middlemen for the ancient world. Their merchants grew wealthy, and with that wealth came the ability to build—first simple structures, and eventually the grand, rock-cut city that stuns visitors today.

Water: The Real Treasure of Petra

It’s tempting to think of Petra as a city of gold and stone, but its real secret was water. The Nabateans were obsessed with collecting, storing, and distributing every drop of rain that fell. Without their water engineering, Petra would have been impossible.

The city’s builders carved a clever network of dams, cisterns, reservoirs, and channels into the mountains. Some channels ran for miles, hugging cliff edges and funneling floodwaters to safe storage. The Nabateans even developed ceramic pipes to carry water underground, protecting it from evaporation and contamination. In total, Petra’s water system could supply tens of thousands of people, plus all the camels and livestock that caravans brought with them.

Archaeological digs have uncovered vast underground chambers used as storage tanks, some holding over 200,000 gallons of water. The remains of ancient sluice gates and terracotta pipes are still visible today. This mastery of water meant the Nabateans could turn Petra into an oasis in a place where nature never meant one to exist.

The Architecture: Carving a City from Rock

Petra’s most iconic structures aren’t built from stone blocks—they’re carved into the cliffs themselves. The process was as much art as engineering. Workers would start at the top of the cliff, carving downward to avoid collapse. They used iron chisels, picks, and hammers, likely working from wooden scaffolds that clung to the rock face.

The result is a city where the line between nature and architecture blurs. The most famous building is Al-Khazneh, or “The Treasury.” Its Hellenistic façade is nearly 40 meters tall, with six Corinthian columns, intricate friezes, and a massive urn perched at the top. The name “The Treasury” comes from a local legend that bandits hid their loot in the urn, but in reality, it was probably a royal tomb.

And that’s just the beginning. Petra is home to over 800 registered monuments, including tombs, temples, altars, colonnaded streets, and even a Roman-style amphitheater carved entirely from the rock. The so-called “Royal Tombs” cluster on the eastern cliffs, their façades blending Nabatean, Greek, Egyptian, and Roman influences. This mixture wasn’t just aesthetic—the Nabateans borrowed and adapted styles from the cultures they traded with, making Petra a living museum of the ancient Mediterranean and Middle Eastern worlds.

Underground Chambers and Ritual Spaces

What’s less visible, but just as significant, is what lies beneath the surface. Petra’s cliffs are riddled with secret chambers—some for storage, some for burial, others for religious ceremonies. Archaeologists have found underground rooms with benches carved into the walls, likely used for feasts honoring the dead. Some of these chambers contain niches for statues or offerings, evidence of the Nabateans’ complex religious life.

The Nabateans worshipped a mix of Arabian deities and adopted gods from other cultures. Their chief god was Dushara, often symbolized by a simple, uncarved block of stone (betyl). Temples and open-air altars dot the hills around Petra, where priests would perform animal sacrifices and pour libations to the gods. One of the most impressive is the High Place of Sacrifice, perched above the city and reached by a steep rock-cut staircase.

If you visit Petra, your journey almost certainly begins with the Siq—a winding, narrow gorge nearly a mile long. The Siq is both a natural and human-made marvel. It was formed by tectonic forces splitting the rock, but the Nabateans modified it, carving channels along the walls to carry water and sculpting niches for idols.

Walking through the Siq is an experience in itself. The walls soar up to 80 meters, and sunlight filters down in shifting patterns. You hear your footsteps echo and the occasional call of a bird, but mostly, it’s silent. Then, at the end of the gorge, the Treasury appears suddenly, framed by the canyon’s shadow—a reveal that still leaves visitors speechless.

Petra’s Expansion: From Nabateans to Romans

Petra’s golden age came in the first century BCE and the first century CE, when the city’s population may have reached 30,000 or more. Its wealth attracted the attention of Rome. In 106 CE, the Roman Emperor Trajan annexed the Nabatean Kingdom and made Petra part of the province of Arabia Petraea.

The Romans brought new architecture and civic improvements. They built a grand colonnaded street, public baths, and expanded the theater to seat 8,500 people (more than double the estimated population). Roman-style mosaics can still be found in the remains of Petra’s churches and houses.

But as trade routes shifted—especially with the rise of sea trade controlled by Rome and later Byzantium—Petra’s importance declined. The city was hit by several earthquakes in the 4th and 6th centuries CE, which destroyed many buildings and water systems. By the early Islamic period, Petra was a shadow of its former self, though small communities lingered on for centuries.

Rediscovery: Petra and the Western Imagination

For centuries after the Crusades, Petra disappeared from most Western maps. Nomadic Bedouin tribes knew the ruins well, but kept their location secret, wary of outsiders. That changed in 1812, when the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, traveling in disguise as a Muslim pilgrim, persuaded his guides to take him to the “lost city.” Burckhardt’s reports electrified Europe—suddenly, tales of a forgotten city carved from the desert rock seemed real.

Since then, Petra has become a magnet for explorers, archaeologists, and travelers. Victorian adventurers mapped its tombs and temples, while early 20th-century excavations began to uncover its secrets. Archaeological work continues today, revealing new details about Nabatean daily life, religion, and engineering.

What Archaeology Tells Us: Life in Petra

Digging beneath Petra’s famous façades, archaeologists have found evidence of a vibrant, multicultural city. Pottery shards and inscriptions reveal that people spoke Nabatean Aramaic, Greek, and later Latin. Imported goods from as far away as India and China have been found in the ruins, along with Egyptian glassware and Roman coins.

The city wasn’t just for the elite. Excavations have uncovered modest houses, workshops, and markets. Animal bones show that Petra’s people ate a mix of local and imported food—goat, sheep, camel, fish, dates, wheat, and spices. The remains of olive presses and wine vats hint at industries that kept the city thriving.

One of the most remarkable discoveries is the Petra Church, built in the Byzantine period. Its floor is covered with intricate mosaics depicting animals, plants, and everyday life, showing how the city adapted to Christian rule after the fall of Rome. In the church’s ruins, archaeologists found an archive of hundreds of papyrus scrolls, providing rare insights into land ownership, trade, and law in 6th-century Petra.

The Bedouin: Petra’s Guardians and Inhabitants

While Petra’s ancient inhabitants are long gone, the site was never truly abandoned. Bedouin families lived in and around the ruins for centuries, using the rock-cut rooms as homes and stables. Their knowledge of the site was crucial to early explorers and archaeologists.

Today, the Bedouin still play a vital role in Petra’s story. Many work as guides, sharing their heritage with visitors and helping to protect the monuments. Their oral traditions preserve legends and stories about Petra that you won’t find in any textbook.

Petra isn’t frozen in time—it’s a living, changing place. The same forces that carved it from the rock now threaten its survival. Wind, rain, flash floods, and even the touch of thousands of visitors each day cause the soft sandstone to erode. Some carvings have faded; others have collapsed entirely.

Preserving Petra is a massive challenge. The Jordanian government, with help from UNESCO and international partners, is constantly working to stabilize structures, manage tourism, and prevent looting. New technology, like 3D scanning and drone mapping, helps archaeologists monitor changes and plan conservation efforts.

Petra in the Modern World

Since being named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985, and later one of the New Seven Wonders of the World, Petra has become Jordan’s biggest tourist draw. Over a million people visit each year, trekking through the Siq, snapping photos of the Treasury, and climbing the 800 steps to the Monastery—a massive, less-visited temple overlooking the valleys.

But tourism is a double-edged sword. While it brings jobs and income, it also puts pressure on fragile ruins and the surrounding environment. Jordan faces the challenge of balancing preservation with progress, making sure Petra survives for future generations.

Petra’s haunting beauty has inspired countless writers, artists, and filmmakers. T.E. Lawrence described it as “the most wonderful place in the world.” Agatha Christie set part of her novel “Appointment with Death” among Petra’s tombs. Hollywood, too, has fallen for Petra—the Treasury served as the entrance to the Holy Grail’s resting place in “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade,” and has appeared in other films and documentaries.

But for many visitors, Petra’s magic isn’t just in its appearance. It’s in the sense of time collapsed, the feeling that you’re walking in the footsteps of traders, priests, and kings from two thousand years ago. It’s in the silence of the Siq at dawn, or the way the setting sun turns the cliffs a deep, burning red.

Petra isn’t just a collection of ruins. It’s proof that human ingenuity can flourish in even the harshest conditions. The Nabateans didn’t just survive in the desert—they built a city that became the envy of empires. They mastered water, carved beauty from bare rock, and created a culture that blended east and west.

Archaeology continues to reveal new secrets. Recent discoveries include hidden tombs, ancient gardens, and inscriptions that hint at lost languages. Each find adds a new chapter to Petra’s story.

If you’re lucky enough to visit, take your time. Walk the Siq slowly. Climb up to the High Place of Sacrifice and look out over the valleys. Sit in the shadow of the Treasury and imagine the caravans arriving from distant lands, the merchants haggling in a dozen languages, the priests lighting incense at dawn. Petra is more than a city—it’s a testament to what’s possible when people dare to dream in stone.

About the Creator

Kek Viktor

I like the metal music I like the good food and the history...

Comments (1)

Petra sounds amazing. I've always been fascinated by ancient architecture. It's incredible how the Nabateans made such a city in the desert. Their water engineering must've been top-notch. I wonder how they managed to carve those structures so precisely. And with all that trade passing through, it must've been a hub of activity. What do you think was the most crucial aspect of their success?