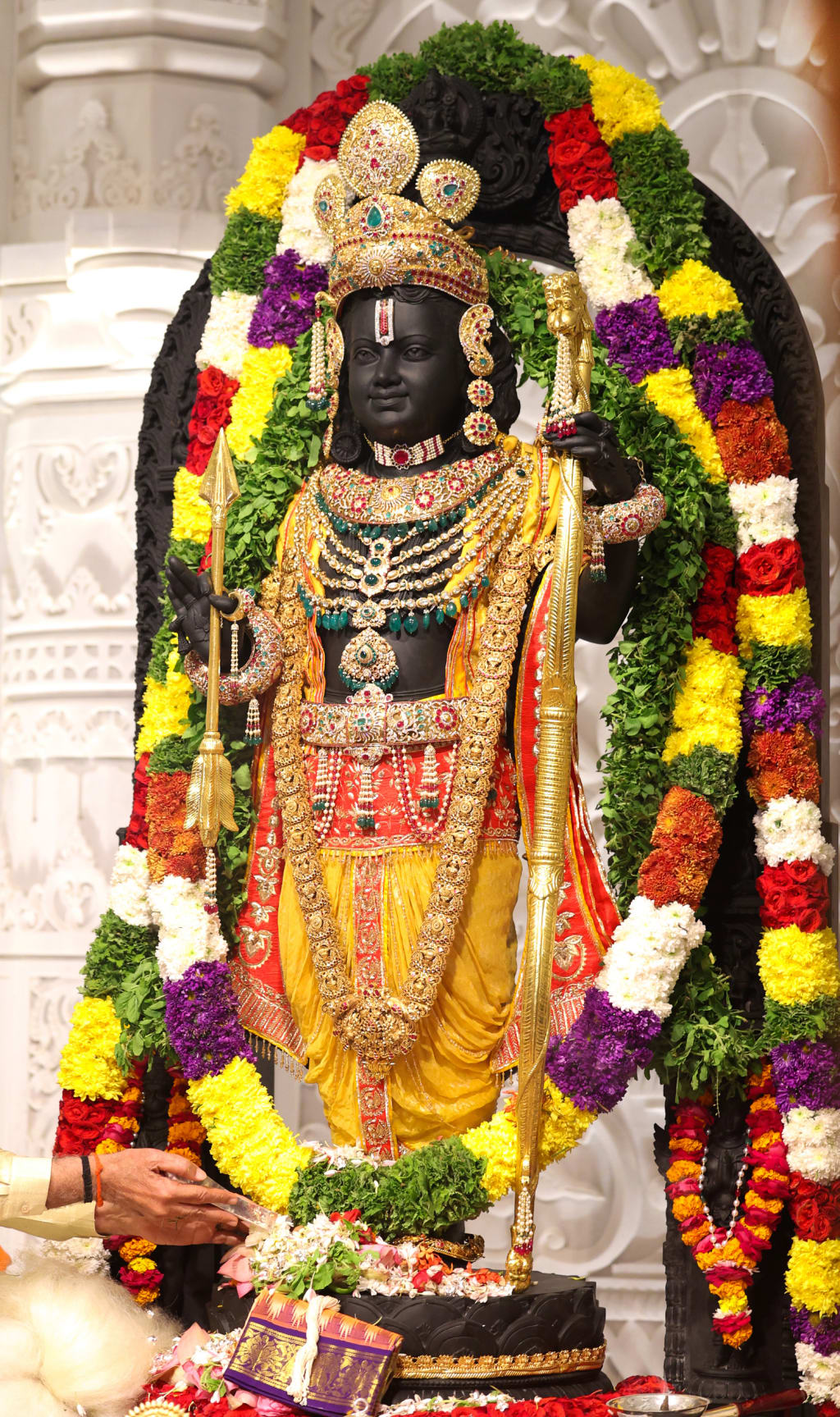

The Ram Mandir Dispute: Unraveling India’s Century-Old Saga of Faith, Politics, and Justice | Part-I

Let us dive into the Historical, Religious, and Legal Journey of India’s Most Controversial Landmark.

The birthplace of Lord Ram has been one of the oldest and most contentious issues in Indian history. Even today, discussing it often evokes strong emotions. This single dispute has not only caused turmoil in Ayodhya or Uttar Pradesh but has also led to riots across India, claiming thousands of lives. It is a case where, metaphorically, Lord Ram himself seemed to fight for his rightful place.

A comprehensive file was created in the Supreme Court to address this matter, culminating in a 1,405-page judgment. This judgment contains intricate details that shed light on why this dispute persisted from the 16th century until the present day. Having read the entire judgment, I aim to present facts directly from the Supreme Court’s findings, government reports, and archaeological surveys, without adding personal bias or speculation. This blog seeks to examine the reasons behind the conflict and understand the Supreme Court’s perspective.

The Disputed Land: A Small Plot with a Big History

In Uttar Pradesh’s Ayodhya district, formerly known as Faizabad, lies a 2.77-acre plot of land, identified as Plot No. 583. This land is at the heart of India’s oldest and most significant land dispute. Today, the Ram Temple is being constructed on this site. The larger area, totaling 67.7 acres, surrounds the disputed land, but the actual contention centers on just 0.313 acres within it.

You may wonder why the temple wasn’t built on the entire 67.7 acres but specifically on this small plot. To understand this, we need to delve into history, step by step.

Ayodhya: From the Kingdom of Kosala to the First Ram Temple

Around 500 BCE, ancient Hindu texts like the Ramayana, Bhavishya Purana, and Lomesh Ramayana mention Ayodhya as the capital of the Kosala kingdom. According to these texts, Lord Ram’s son, Maharaja Kush, constructed the first Ram Temple at his father’s birthplace in Ayodhya. Successive generations of rulers maintained the temple, with 44 kings ruling the region. The last of these kings, Brihadbala, fought in the Mahabharata and was killed by Abhimanyu. After his death, Ayodhya and the temple fell into disrepair.

Reconstruction by Maharaja Vikramaditya

In 57 BC, Ujjain’s King Maharaja Vikramaditya visited Ayodhya during a hunting expedition. Upon learning about its historical and spiritual significance from local saints, he was inspired to restore the Ram Temple and redevelop the city. The Supreme Court’s judgment on page 673 acknowledges this significant contribution. For a time, Ayodhya flourished under Vikramaditya’s patronage.

The Mughal Era and the Construction of Babri Masjid

The year 1526 marked a significant turning point in Indian history with the Battle of Panipat, where Babur defeated Ibrahim Lodhi to establish Mughal rule in India. This victory ushered in a new era, and with it came a common practice of the time, that the rulers who conquered territories often replaced the religious structures of the existing faith with those of their own, as a symbol of dominance and authority.

Two years later, in 1528, Babur’s commander, Mir Baqi, arrived in Ayodhya and oversaw the construction of the Babri Masjid on a 2.77-acre plot located in a village ‘Ramkot’ or ‘Kot Ramchandra’, where Kot translates to a fort or stronghold. Historical records, including Tarikh-i-Avadh by Muhammad Qasim and Akhbar-i-Mas’ud by Abd al-Qadir, indicate that the mosque was built on the site of a pre-existing temple. This act, consistent with the practices of the era, reflected the assertion of Mughal influence in the region.

Local Resistance and Early Documentation

From the time of the mosque’s construction, local villagers quietly voiced their opposition, asserting that the site was the birthplace of Lord Ram. As the Mughal Empire began to weaken, this sentiment grew stronger. By 1857, with the Mughal rule nearing its end, accounts from European travelers like William Finch and Joseph Tiefenthaler documented Hindu worship practices at the site.

These travelers often wrote extensively about Ayodhya, the Ram Temple, and the devotion of the people who prayed there. William Foster, in his book Early Travels in India, also mentioned these practices. Notably, Tiefenthaler created a detailed map of the area, which later played a critical role in the Supreme Court’s judgment, serving as written evidence of the temple’s prior existence. Page 663 of the judgment highlights these records, emphasizing the importance of the travelers’ notes in establishing the historical significance of the site.

Sawai Jai Singh and the Ram Chabutra

As the Mughal empire waned, Sawai Jai Singh of Jaipur took an interest in Ayodhya’s Ram Temple and was very concerned. Unable to reclaim the mosque, he purchased adjacent land and constructed the Ram Chabutra, a raised platform where Hindus could worship from outside the mosque. Devotees began offering prayers at the Chabutra, facing the mosque’s central dome.

British Intervention and the First Recorded Riots

When the British took control of India, they were soon drawn into the conflict. In 1838, British administrator Robert Montgomery Martin conducted a survey and submitted a report stating that a temple had existed on the disputed land. However, he could not confirm whether the mosque was built after demolishing the temple or on vacant land. His findings, detailed on pages 669–71 of the Supreme Court’s judgment, further fueled tensions. These records reinforced the belief among many that the site was the birthplace of Ram Lalla and that the Babri Masjid had been constructed on it.

The tensions surrounding the site continued to escalate, and by 1853, the situation took a violent turn. Just a few yards away from the birthplace of Lord Ram stood Hanuman Garhi, a temple maintained by Bairagi saints belonging to the Nirmohi Akhara. Following Martin’s report about unrest in the area, the saints of Hanuman Garhi alleged that the Babri Masjid had been constructed after demolishing a Ram temple. Seeking to take control of the mosque, they initiated an attempt that led to riots — the first recorded conflict over the site. This marked the beginning of heightened tensions between Hindus and Muslims, with riots continuing for the next two years.

In 1855, a Sunni cleric named Ghulam Hussain claimed that Hanuman Garhi itself was built after demolishing a mosque. He gathered nearly 500 Muslim followers and launched an attack on Hanuman Garhi. However, the Bairagi saints, numbering around 8,000, were prepared and defended the temple. A fierce battle ensued, resulting in significant losses for the Muslim side, with 75 lives lost. These events are detailed in Sarvepalli Gopal’s book Anatomy of a Confrontation and are also mentioned on page 675 of the Supreme Court’s judgment. The riots caused widespread unrest, troubling the British authorities. In an attempt to restore order, the British divided the disputed land between Hindus and Muslims, hoping this measure would ease tensions. However, the division failed to bring lasting peace, as the underlying conflict persisted.

British Divide and Rule

Disturbed by the recurring unrest, the British attempted to divide the disputed land between Hindus and Muslims. However, this measure did little to resolve the underlying tensions. Instead, it set the stage for a protracted legal and communal conflict that would continue for over a century.

In 1857, the British constructed a 6–7 feet tall wall using bricks and grills on the disputed land. This wall, marked as the N, H, O, P, J, K, and L line on the map, divided the area into two sections. Hindus began praying in the outer portion, while Muslims continued offering Namaz in the inner portion. Neither community was content with this arrangement, but under British rule, they had no choice but to comply.

The Mahant Nihang Singh Incident (1858)

On November 28, 1858, Punjab’s Mahant Nihang Singh Fakir, accompanied by 25 Nihang Sikhs, entered the disputed site, believed to be the birthplace of Lord Ram. They performed Havan and prayers inside the mosque, while the Nihang Sikhs surrounded the mosque, inscribing “Ram” on its walls with coal and they even prayed to Guru Nanak Ji. They also increased the height of the Ram Chabutra, placed a picture of Lord Ram, and expanded the prayer area. The mosque’s Muezzin, Sayyed Muhammed Khateeb, filed a written complaint with the local Thanedar, Sheetal Dubey, detailing these actions. Authorities intervened and forced the Nihang Sikhs out, but tensions persisted. The simultaneous calls for Azaan and the playing of the conch shell escalated conflicts, leading to repeated complaints from both sides.

The Temple Construction Dispute (1877–1886)

In 1877, Hindus demanded the opening of Singh Dwar for a second entry point to the disputed site, which was approved by authorities. However, in 1883, Mahant Raghuvar Das, the priest of Ram Chabutra, sought permission to construct a 17x21 feet temple in the outer portion. On January 19, 1885, the Deputy Commissioner denied the request, fearing communal riots. Undeterred, Mahant Raghuvar Das filed a case on January 27, 1885, which was dismissed on March 18, 1886. The court ruled that maintaining the status quo was essential to avoid unrest. A subsequent appeal on November 1, 1886, was also rejected, with the court asserting that the Mahant had no ownership rights.

The 1934 Riots and Mosque Reconstruction

On March 27, 1934, a cow slaughter incident in Shahjahanpur village, Ayodhya, sparked widespread riots. During the unrest, the Babri Masjid was attacked, resulting in significant damage to its walls and dome. The British India Government later undertook the reconstruction of the mosque. A fine was imposed on the Bairagis, the Vaishnavite Hindu priests, and other rioters to cover the cost of the mosque’s repairs.

Following this incident, however, Muslims began avoiding offering Namaz at the mosque. They cited violations of Shariyat, believing it was improper to pray in a place where Hindus also conducted their religious activities. The outer portion of the site, which had been allocated to Hindus, continued to be a place of worship. Bhajans were sung, prayers were conducted, and the area remained an active center for Hindu devotion.

The dual use of the site, with Hindus praying in the outer portion and Muslims refraining from Namaz inside the mosque, further highlighted the growing divide and lingering tensions between the two communities.

Continued in my second article: The post-independence developments and the efforts to reclaim Lord Rama’s birthplace.

***

Thank you for reading! Here are a few more interesting reads that could make a meaningful difference.

If you enjoy my articles or have any suggestions, feel free to share your thoughts and give hearts as a token of appreciation!

About the Creator

Adarsh Kumar Singh

Project Analyst with military training and startup experience. Avid reader, content writer, and passionate about leadership and strategic planning.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.