🪨Derinkuyu: The Ancient Underground City of Cappadocia in Turkey

⛏️A Subterranean World of Survival, Mystery, and Ingenuity"

🪨Derinkuyu: The Ancient Underground City of Cappadocia in Turkey

🌍 Deep beneath the arid plains of central Turkey, in the heart of the Cappadocia region, lies one of the most remarkable feats of ancient engineering ever discovered: the underground city of Derinkuyu. This vast subterranean complex, carved into soft volcanic rock, descends more than 85 meters (approximately 280 feet) below the earth’s surface and contains a network of tunnels, chambers, staircases, wells, and ventilation shafts that once served as a fully functioning city. It could house up to 20,000 people, along with their food, livestock, and belongings. The scale, complexity, and historical significance of Derinkuyu make it one of the most fascinating archaeological discoveries of the modern era.

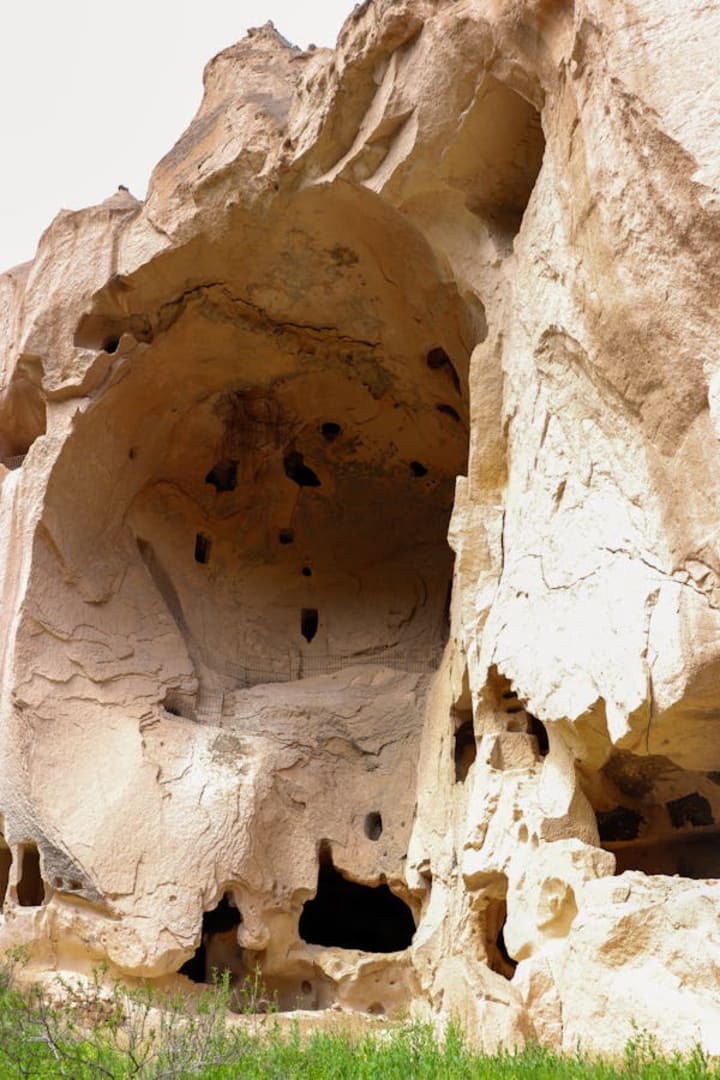

🪨 The geological conditions of Cappadocia were crucial to the construction of Derinkuyu. The region is composed of tuff, a soft and malleable volcanic stone formed from compressed ash following ancient eruptions. This rock is durable once exposed to air but relatively easy to carve, making it ideal for subterranean architecture. Early settlers in the area, likely starting in the 8th or 7th century BCE, began chiseling into the earth to create basic storage rooms and shelters. The Phrygians, an Indo-European people who occupied central Anatolia during this period, are considered the probable originators of the earliest sections of Derinkuyu. Over time, and through the contributions of multiple civilizations, the site evolved into a sophisticated multi-level underground metropolis.

👣 As empires rose and fell, and invasions swept through the Anatolian plateau, Derinkuyu was expanded and refined by successive cultures. The early Christians, particularly during the Byzantine period (approximately 4th–11th centuries CE), made significant additions to the underground city. These communities, facing persecution from pagan Roman authorities and later threats from Arab and Mongol invasions, found in Derinkuyu not only a sanctuary but also a sustainable living space. Evidence suggests that entire populations could retreat underground for weeks or even months during periods of siege or violence. The ability to vanish beneath the earth likely saved countless lives.

🛡 Security was central to the city’s design. Entrances were well-hidden, often concealed within the courtyards or basements of above-ground dwellings. Massive rolling stone doors, some over a meter in diameter and weighing up to 500 kilograms (1,100 lbs), could be rolled into place to seal off passageways between levels or block enemy movement. These doors could only be operated from the inside, ensuring that once a level was secured, intruders had no hope of advancing deeper into the complex. The passageways were intentionally narrow and low-ceilinged—an invader unfamiliar with the layout would be forced to enter single-file and crouching, giving defenders a significant advantage.

🌬 One of the most impressive features of Derinkuyu is its ventilation system. The entire city is pierced by an elaborate network of vertical shafts, some of which descend directly from the surface. These shafts functioned not only to circulate air but also to provide fresh water from underground aquifers. The largest of these shafts—measuring about 55 meters deep—served as a well, supplying both the underground city and surface dwellers. Crucially, this well could be shut off from below, preventing contamination or poisoning during enemy occupation.

🏘 Within Derinkuyu’s labyrinthine corridors are spaces that reflect a fully self-sustaining community. There are residential quarters, sleeping chambers, communal kitchens with blackened soot still coating the walls, and food storage rooms built with natural insulation to preserve grain and perishables. There are also winemaking and oil pressing areas, indicative of both ritual and daily domestic practices. Religious life was also maintained underground: a prominent room on the second level, with a barrel-vaulted ceiling, is believed to have served as a religious school, complete with side chambers that likely functioned as classrooms or monks’ cells. Additionally, archaeologists have identified chapels used for Christian worship, their niches carved into the walls to hold lamps and icons.

🐄 The underground city even had spaces designated for livestock, with ventilation and waste systems in place to manage their presence. This was vital, as in times of siege, communities would need to survive without contact with the surface for extended periods. Other features include communal meeting rooms, burial spaces, and even a missionary corridor—a long, narrow hallway thought to have been used for stealthy movement or communication between groups.

🔍 Historical records, including letters from the 8th-century scholar Alcuin of York, describe the fear and displacement caused by foreign incursions into Byzantine territory. These records, alongside findings from archaeological digs, suggest that Derinkuyu was used multiple times as a refuge during Arab invasions between 780–1180 CE. Later, during the Mongol invasions in the 13th century, Derinkuyu and other underground cities in Cappadocia likely again sheltered Christian populations, particularly those aligned with the Byzantine Empire and later, the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, which controlled the region.

🕌 Although primarily used by Christians, Derinkuyu’s inhabitants spanned centuries of religious and political change. During the Ottoman period, the city likely fell into disuse, but the region remained home to Anatolian Greek communities, who passed down oral traditions about secret underground refuges. In 1923, the Greco-Turkish population exchange led to the departure of Cappadocia’s last significant Christian population, and knowledge of the underground city was almost completely lost.

🛠 That is, until 1963, when a man in the Nevşehir Province demolished a wall in his basement and discovered a hidden chamber. Behind it lay a maze of tunnels and rooms descending into the earth. Archaeologists were soon alerted, and the rediscovery of Derinkuyu stunned the world. What had once been passed off as legend or myth was now revealed as a vast and real underground complex. Further exploration unearthed 18 stories, although only eight levels are currently open to the public due to safety concerns. The city connects with other underground settlements, including Kaymakli, via tunnels stretching over 8 kilometers (5 miles)—a testament to the regional scale of underground life in ancient Cappadocia.

🔬 From an archaeological perspective, Derinkuyu remains a site of continuous fascination. The absence of modern lighting, the acoustic properties of the chambers, and the darkness of the volcanic tuff give the underground complex a timeless atmosphere. Researchers studying airflow, water conservation, and sustainable architecture have marveled at how ancient builders created a habitable, oxygenated space underground without any mechanical systems. Theories about the site’s origin vary, with some suggesting Hittite or even earlier Anatolian roots, though the majority consensus remains that it began with the Phrygians and expanded under Christian Byzantine rule.

🧩 The city has become a subject of many hypotheses and debates. Some fringe theorists have suggested Derinkuyu could have been designed as a shelter from not just war but natural disasters or even extraterrestrial threats—though mainstream scholars firmly reject such claims. Others compare Derinkuyu’s construction to similar subterranean complexes in Iran, China, and Italy, seeing it as part of a broader tradition of ancient underground urbanism that responded to similar pressures: warfare, climate, and religious persecution.

🎒 Today, Derinkuyu is protected by the Turkish government and is part of the Göreme National Park and the Rock Sites of Cappadocia, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1985. The site draws thousands of visitors each year, with tourists descending narrow staircases into a shadowy world beneath the surface. Despite safety concerns and closed-off areas, the open levels provide a staggering look at how ancient people adapted to life underground. Guide rails, electric lights, and ventilation grilles allow modern travelers to explore with some comfort, but the sense of awe remains—an unmistakable echo of the endurance and creativity of those who once lived in darkness to survive.

🧠 Derinkuyu is more than a historical curiosity. It’s a lens into how ancient societies dealt with extreme stress—be it religious persecution, war, or natural hardship. Its construction demonstrates not only architectural intelligence but also collective will. Thousands of people working together over generations carved out a civilization beneath the soil. Their work still stands today, shielded from the weather and frozen in time. It is a monument to resilience, a vast underground city where every stone was placed with purpose, every tunnel told a story, and every chamber echoed the footsteps of those who refused to surrender to the world above.

About the Creator

Kek Viktor

I like the metal music I like the good food and the history...

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.