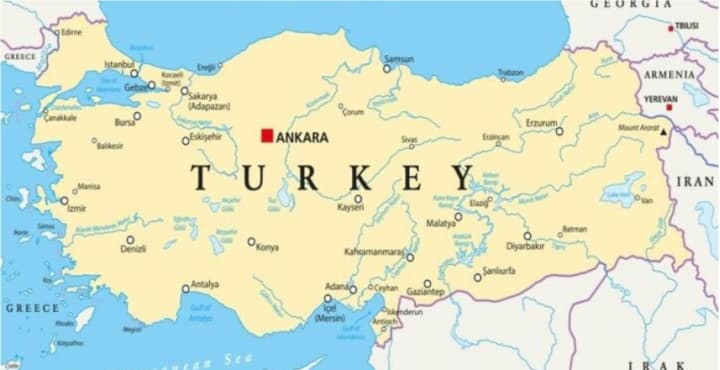

I knew nothing about the Turkish evil eye beads and pendants, or traditional glass work made by the artisans in Turkey until my wife Jme and I attended the International bead conference held in Istanbul, Turkey in 2007. We learnt a lot and saw first hand how the glasswork was made using the ancient technique. Turks make traditional glass beads, especially the famous evil eye beads (nazar boncuğu), primarily in villages near Izmir, such as Nazarköy (formerly Kurudere) and Görece, where artisans carry on age-old techniques, with some workshops also found in Istanbul. These areas have historical roots tracing back to Ottoman-era artisans who moved from central Izmir to escape fire risks, preserving the craft through generations, though the industry faces challenges and modernization. make traditional glass beads, especially the famous evil eye beads (nazar boncuğu), primarily in villages near Izmir, such as Nazarköy (formerly Kurudere) and Görece, where artisans carry on age-old techniques, with some workshops also found in Istanbul. These areas have historical roots tracing back to Ottoman-era artisans who moved from central Izmir to escape fire risks, preserving the craft through generations, though the industry faces challenges and modernization.

Key Locations:

Nazarköy (Kurudere), İzmir: This village is famous for its centuries-old tradition of glass evil eye bead making

Görece, İzmir: Another significant center for traditional bead-making, similar to Kurudere.

Istanbul (Üsküdar): Contemporary glass artists and studios, such as Flame Glass Art and Hanecambaz Cam Sanat Atölyesi, offer workshops and create unique beads. We have been there, and saw them making beads, which we bought and imported into the States. We still sell these beads and pendants.

Key Locations:

Nazarköy (Kurudere), İzmir: This village is famous for its centuries-old tradition of glass evil eye bead making

Görece, İzmir: Another significant center for traditional bead-making, similar to Kurudere.

Istanbul (Üsküdar): Contemporary glass artists and studios, such as Flame Glass Art and Hanecambaz Cam Sanat Atölyesi, offer workshops and create unique beads using flame-working techniques.

Craftsmanship:

Beads are made using traditional methods, often with recycled glass, and involve working with intense heat.

The distinctive blue and white evil eye beads, intended to ward off bad luck, are a hallmark of these Turkish artisans.

Both Greek and Turkish cultures heavily use the evil eye motif as a protective amulet against envy, but the Turkish nazar boncuğu is famous for its distinct blue glass bead, while Greek mati (eye) symbols are also prevalent, sharing roots in ancient Mediterranean belief systems, often intertwining due to historical proximity, with Turkey popularizing the iconic blue charm globally.

Key Differences & Similarities

Names: In Turkey, it's the nazar boncuğu (evil eye bead) or simply nazar; in Greece, it's mati (eye) or mataki.

Appearance: The iconic, bold blue glass bead is strongly associated with Turkey, though similar blue-eyed amulets are found everywhere. Greek versions often feature blue and white concentric circles, similar to the Turkish style.

Origin & Belief: Both cultures believe a jealous glare can cause misfortune, and the eye symbol reflects this harm back. The belief is ancient, spanning many cultures, but Turkey popularized the blue glass charm widely.

Usage: Both pin charms on babies, hang them in homes/cars, and use them in jewelry (necklaces, bracelets) for protection. We also found out most Turks pin small eyes onto their underwear, hidden so no one can see that they are superstitious.

Cultural Nuances: Greeks have specific words for casting (matiazo) and removing (xematiazo) the eye. Turks sometimes use red ribbons or Hamsa hands alongside the nazar. The Hamsa Hand and the Evil Eye are ancient symbols of protection, often combined in jewelry and decor to ward off bad luck, negative energy, and the "evil eye" curse itself, which is a malevolent glare bringing misfortune; the Hamsa (Hand of Fatima/Miriam) offers general divine protection and blessings, while the Evil Eye (Nazar) specifically reflects envious gazes, creating a powerful, dual-layered defense.

In Essence

The evil eye motif is a shared cultural heritage, especially in the Aegean region where Greeks and Turks lived side-by-side. While Greece has deep ancient roots with the concept, Turkey's mass production of the blue nazar bead made it a global symbol, leading to the common "Turkish eye" label, though it's a beloved, shared protective symbol for both.

What Exactly Is the Evil Eye?

The “evil eye” isn’t just a piece of jewellery – it’s a centuries-old belief and symbol found in many cultures. At its core, the evil eye is the idea that a malevolent glare or envy-charged look can curse or bring bad luck to the person receiving it. To protect against this jinx, people created amulets in the shape of a watchful eye. The concept dates back thousands of years: archaeologists have found eye amulets in ancient Mesopotamia, and references to the evil eye appear in Greek and Roman texts. Essentially, the evil eye charm acts like a spiritual shield, reflecting back any ill will. Over time, this protective amulet evolved into the fashionable evil eye jewellery we know today – from dainty pendants to beaded bracelets – allowing wearers to carry a bit of good luck and style wherever they go.

Where Did the Evil Eye Belief Originate?

With its presence in so many lands, pinning down the exact origin of the evil eye belief is tricky. The tradition likely arose independently in multiple ancient civilizations. Some historians trace the first evil eye amulets to ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) around 5,000 years ago, where clay tablets mention warding off a cursed gaze. The concept then spread across the Mediterranean and Middle East. Ancient Greeks and Romans were deeply wary of the “evil eye” – classical authors like Hesiod and Plutarch wrote about it, and Romans even wore phallic charms or used hand gestures to fend it off . Meanwhile, early Jewish, Islamic, and Hindu cultures also developed evil eye folklore. In short, the belief in a curse via envious eyes is a shared human superstition that popped up in many places. By the time we reach the Ottoman era, the evil eye symbol (especially the blue-glass amulet form) was already popular in what is now Turkey and Greece. Rather than having a single birthplace, the evil eye legend grew from a mosaic of cultures over millennia.

Is the Evil Eye Originally Greek or Turkish?

Considering its ancient, far-flung roots, is it fair to call the evil eye either Greek or Turkish? The truth is, both cultures are huge contributors to the evil eye’s fame, yet neither can claim exclusive ownership. Greek and Turkish traditions have each embraced and shaped the evil eye belief for centuries. In Greece, the evil eye (known as “mati”, meaning “eye”) has been a household concept since antiquity – any Greek yiayia (grandmother) will warn you about a jealous glare causing headaches or bad luck! Turkey, on the other hand, became famed for its blue glass nazar beads, churning out countless eye charms in bazaars and workshops, especially during the Ottoman period. These amulets became so ubiquitous that many people today refer to the blue charm simply as the “Turkish eye.”

Importantly, Greek and Turkish people historically lived side by side across the Eastern Mediterranean (think of the Ottoman Empire, where cultures mixed), so the evil eye customs intertwined. You’ll find very similar beliefs and even identical blue-eye trinkets in both Athens gift shops and Istanbul markets. In fact, Greeks and Turks often playfully debate who started it – but it’s more accurate to say the evil eye symbol transcends borders. It’s a bit like asking who invented bread! Both cultures (and many others) have baked this metaphorical loaf for ages. So, the evil eye isn’t exclusively Greek or Turkish – it’s both, and so much more. Each culture contributed to making the evil eye amulet the global icon it is today.

What Does the Evil Eye Mean in Greek Culture?

In Greek culture, belief in the evil eye runs deep. Nearly every Greek family has a story about “to mati” – perhaps an uncle who felt dizzy after a stranger’s envious compliment, only to be cured when a friend performed a secret prayer to remove the spell. The evil eye is called “kakó máti” (bad eye) or often just “mati”. Greeks traditionally fear that an envious look – even an unintentional one – can cause headaches, nausea, or a streak of bad luck. It’s common even today for a Greek to quietly mutter “ftou ftou” (spitting sound) or pin a little blue bead on a baby’s blanket to ward off evil stares after someone gushes over how cute the child is. Don’t be surprised if a Greek host adds “me skótoses me to mati!” (“you killed me with the evil eye!”) jokingly if they suddenly feel unwell at a gathering – half in jest, half serious.

To guard against this curse, Greeks turn to mati charms. Greek eye jewellery often features a striking eye motif, usually in hues of blue and white. You’ll see evil eye bracelet designs with tiny enamel eyes alternating with beads, or a evil eye necklace pendant in the shape of a solitary eyeball charm set in gold or sterling silver. Traditionally, some Greek mati charms were even filled with specific herbs or incense, harkening back to Byzantine times, though modern ones are usually solid glass or painted ceramic. Beyond jewellery, the mati symbol appears everywhere in Greece: keychains, wall hangings, even painted on fishing boats for protection at sea. For Greeks, an evil eye charm is both a cultural emblem and a practical talisman – it says “I’m protected, and proud of my heritage.”

What Does the Evil Eye Mean in Turkish Culture?

Walk through any Turkish bazaar or step into a home in Turkey, and you’ll likely be greeted by the watchful gaze of a dozen blue eyes! In Turkey, the evil eye belief is known as “nazar”, and the typical amulet is called “nazar boncuğu” (literally “evil eye bead”). Turkish culture holds that jealous admiration or praise can unintentionally harm the subject of the compliment – a concept almost identical to the Greek one. To counteract this, Turks have their own clever customs. One famous tradition is saying “Maşallah” (an Arabic word meaning “God has willed it”) whenever praising a baby, a new car, or someone’s good health. It’s a verbal way to ward off envy by crediting God, thereby hopefully nullifying any evil eye. But the most visible Turkish solution is the legion of blue eye amulets everywhere.

Turkish eye jewellery and charms are typically made of handmade glass, featuring concentric circles of dark blue, white, and light blue (with a black dot at center to resemble a wide-open eye). These glass evil eye beads have been crafted in Anatolia for many generations – you can even visit workshops in Turkey where artisans blow and shape the molten glass into the classic eye design. Turks proudly hang large nazar discs in their homes and offices, dangle keychain versions from car mirrors, and yes, wear them as jewellery too. An evil eye bracelet with Turkish nazar beads or a pendant with a single bold blue eye is thought to protect the wearer from misfortune by “staring back” at any ill-wisher. In Turkey, gifting a nazar charm to someone moving into a new house or starting a new business is common, to safeguard their fresh start. With its vibrant cobalt hue and folk charm, Turkish

About the Creator

Guy lynn

born and raised in Southern Rhodesia, a British colony in Southern CentralAfrica.I lived in South Africa during the 1970’s, on the south coast,Natal .Emigrated to the U.S.A. In 1980, specifically The San Francisco Bay Area, California.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.