Cults of Gods: Dionysus, God of Peoples

What were Dionysus' cult and religious functions?

Among the Olympian gods, Dionysus occupies a unique and often misunderstood position. He was not merely the god of wine or ecstatic madness, but a deity whose worship belonged to crowds rather than kings, festivals rather than palaces, and shared frenzy rather than private prayer. Dionysus was a god experienced collectively—through procession, theater, initiation, and ritual excess—and for this reason he may best be understood as the god of peoples. His cult reveals how ancient Greek society made room for disorder, emotional release, and sacred transgression within an otherwise highly ordered world.

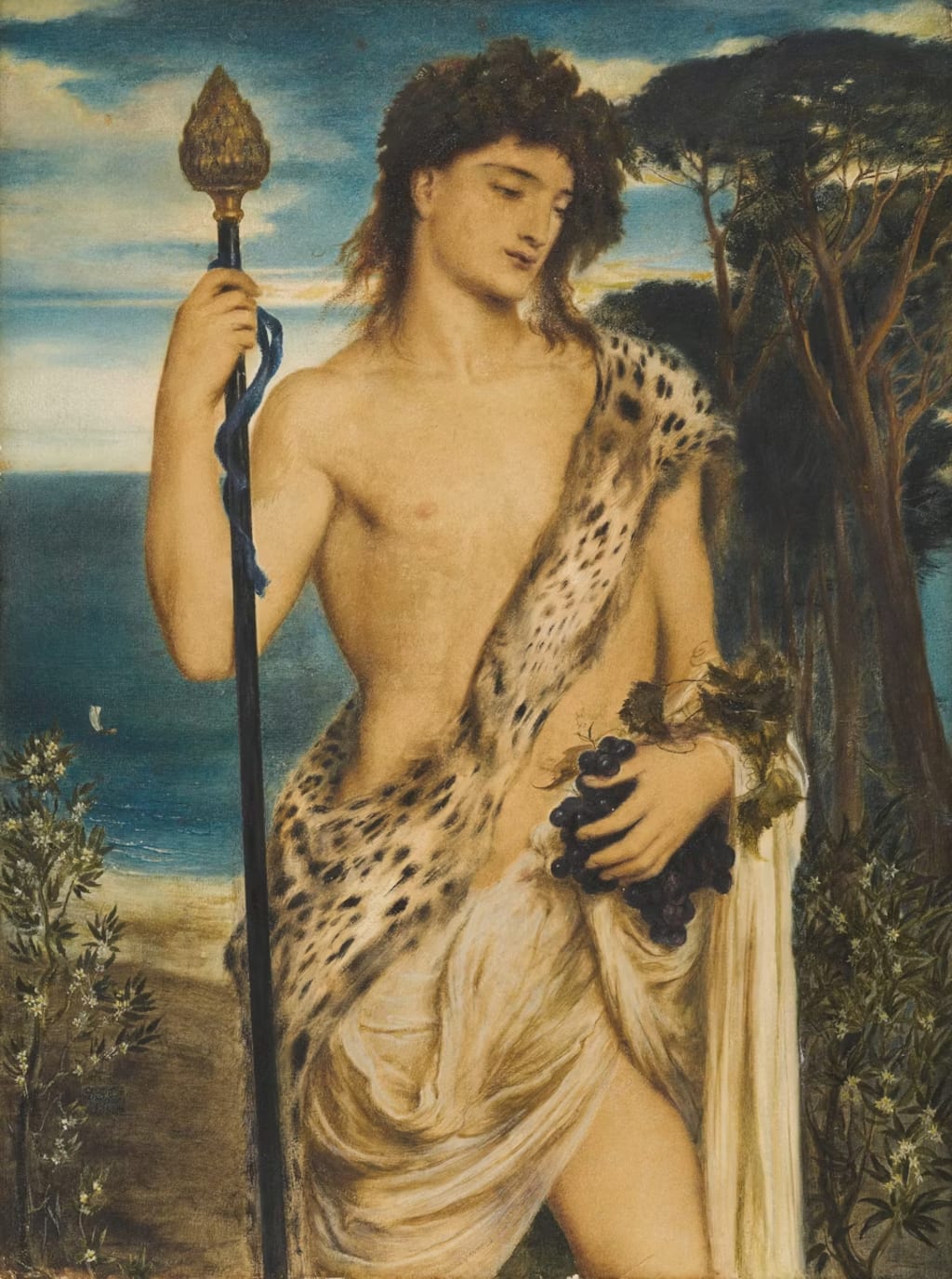

Dionysus is the Olympian god of wine, vegetation, pleasure, festivity, madness and wild frenzy. He was depicted as either an older, bearded god or an effeminate, long-haired youth. His attributes included the thyrsos (a pine-cone tipped staff), a drinking cup and a crown of ivy. He was usually accompanied by a troop of Satyrs and Mainades (wild female devotees).

The deity's name (Greek Διόνυσος, translit. Diónysos; Homeric Greek Διώνυσος, translit. Diṓnysos, Aeolic Greek Ζόννυσος, translit. Zónnysos) was first recorded on Mycenaean tablets from the twelfth or thirteenth century BCE. Originally written in a script called Linear B (which predates the Greek alphabet), the name appears on these tablets as di-wo-nu-so.

There is no consensus as to the exact meaning of the god’s name, but most philologists believe the word is rooted in Dios, the possessive (genitive) form of the name “Zeus” (Dionysus’ father).

The latter part of his name may be derived from Mount Nysa, where the infant Dionysus was thought to have been raised by nymphs, known as the Nysiads. Thus, when put together, “Dionysus” probably meant something like “the Zeus of Nysa” or “of Zeus and Nysa.”

Other etymologies for Dionysus’ name have also been suggested, and scholars disagree on which is the most accurate. Robert Beekes (a Dutch linguist), arguing that all attempts to trace the name to Indo-European languages have proven dubious, has suggested a pre-Greek origin.

Most of his epithets reflect his power to bring leisure, ecstasy and partying in various aspects , such as Hestiôs (Of Feasts), Auxitês (Giver of Increase) and Lysios (of Release). On top of that, he controls wine and pleasure as bringers of progress; such a feature is reflected in epithets like Theoinos (God of Wine), Melpomenos (Of the Tragedy Play). Another reason Dionysus was prayed to is because he could save from madness which is reflected in epithets like Sôtêrios (Recovery from Madness) and Agyieus (Protector of Streets).

The worship of Dionysus had become firmly established by the seventh century BC. He may have been worshiped as early as c. 1500–1100 BC by Mycenaean Greeks; and traces of Dionysian-type cult have also been found in ancient Minoan Crete.

On Naxos one can still see the remains of an especially ancient sanctuary of Dionysus. The site was probably in use as early as the fifteenth or fourteenth century BCE, but the temple whose columns are still standing today dates from around the sixth century BCE. There were also many temples of Dionysus in the region of Boeotia, where the god’s mother Semele lived.

In Athens, there was a temple of Dionysus connected with the theater complex at which the god was honored a few times per year. This temple was said to have been quite ancient and included paintings of various scenes from Dionysus’ mythology.

In Argos, there was also a temple of Dionysus that was said to be very ancient. The Argives claimed that Dionysus buried his beloved Ariadne near this temple after she was killed by Perseus. The cult image inside was thought to have been there since the time of the Trojan War.

During the Hellenistic and Imperial Roman periods, associations or colleges of Dionysus became larger and more important (examples include the Lobakchoi of Athens, the Bakchiastai of Cos and Thera, and the Bakcheastai of Dionysopolis). As a result, Dionysus became one of the most widely worshipped gods of the ancient Mediterranean.

Dionysus was honored with many festivals across many different cities and regions. Some of these were annual, but others were only celebrated every third year (e.g., Dionysus’ festivals at Delphi, Thebes, Camirus, Rhodus, Miletus, and Pergamum).

The festivals and rituals of Dionysus were characterized by licentiousness, revelry, and the reversal of social roles. The most famous of these festivals were orgia (“orgies”)—riotous rituals that included dancing, singing, intoxication, and sacrifice. These events could be so raucous that some ancient cities and regions (including Attica) prohibited their practice.

Another important component of Dionysus’ cult was the phallic procession, a long procession of worshippers who marched behind a large sculpted phallus.

Dionysus was sometimes said to have received human sacrifices, but there is no concrete evidence for this. Even if Dionysus did receive human sacrifice at some early stage in his worship, this custom almost certainly came to an end by the Classical period and was replaced with more traditional animal sacrifice.

Animals commonly sacrificed to Dionysus included pigs, sheep, and goats; goats and rams became particularly associated with the cult of Dionysus. The god also received non-meat sacrifices such as produce, gifts, and cakes.

Some of the festivals honoring Dionysus were more “family friendly” than the orgia. In Athens, the most famous annual festival of Dionysus was the Great Dionysia (sometimes called the City Dionysia). This fantastic, multiday celebration included processions, sacrifices, and theatrical performances; it was here that many of the most famous plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes were originally performed.

Other Dionysus festivals in Athens included the Lenaea, another dramatic festival; the Rural Dionysia, whose central events were a phallic procession and contests; and the Anthesteria, called the oldest Dionysia, a kind of day of the dead in which the souls of those who had died were said to rise from the Underworld and wander the world of the living.

The Athenians also celebrated Dionysus at the Oschophoria (held after the conclusion of the grape harvest), the Theionia, and the Iobakcheia, though much less is known about these festivals.

Other rituals of Dionysus were connected with death (like the Athenian Anthesteria). In Argos, for example, Dionysus was summoned from the water by throwing a lamp into an abyss for Hades and then blowing on a trumpet concealed in thyrsi. The Delphians even displayed a tomb of Dionysus.

Dionysus was a major god in ancient Greek mystery religions—religions that required initiation and forbade initiates from revealing their rites to the uninitiated. The Dionysian Mysteries were not limited to a particular geographic location; rather, they were organized by private communities of followers, made up of both men and women.

Fueled by wine, music, and dance, the Dionysian Mysteries brought worshippers together in frenzied, orgiastic celebrations that freed them from social inhibitions. Many revelers wore masks to disguise themselves, and it was said that Dionysus himself would often appear among the throngs. These mysteries seem to have promised their initiates rebirth and even deification rather than a blessed afterlife.

Thank you for reading my article! Share your thoughts in the comments and spread this article.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.