Unveiling Nigeria’s Ancient Kingdoms

Part 1: The Rise of Early Nigerian States and the Yoruba Kingdoms

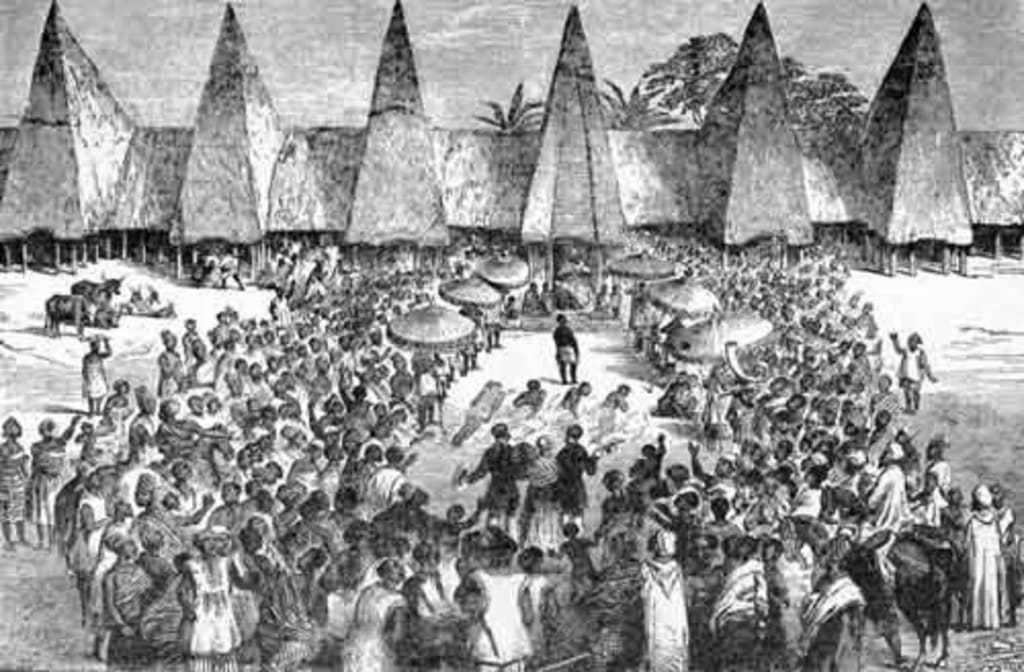

Before the year 1500, the lands we now know as Nigeria were a rich collection of states, a vibrant patchwork reflecting the ethnic groups that still exist today. These early states gave birth to the Yoruba kingdoms, the regal Edo Kingdom of Benin, the bustling Hausa cities, and the beautiful land of Nupe.

Small states scattered to the west and south of Lake Chad were swallowed up or displaced by the burgeoning power of Kanem, a kingdom nestled to the northeast of Lake Chad. Borno, once just the western province of Kanem, proudly declared independence in the late 14th century. We’ve heard whispers of other states too, lost in the mists of time due to the absence of archaeological data and reliance on oral traditions.

Now, let’s stroll through the Yoruba kingdoms and Benin, where the Yoruba people have long held sway on the west bank of the Niger. This dynamic group has a diverse origin, a melting pot of migrant waves who over time wove together a shared language and culture. The Yoruba's humble beginnings were in agriculture-based village communities organized along patrilineal descent lines. But around the 11th century A.D., something remarkable happened: neighboring village compounds known as Ile began merging to form territorial city-states.

Loyalties to the clan took a back seat to allegiance to a dynastic chieftain, giving birth to a thriving urbanized society pulsating with artistic achievements. Terracotta and ivory sculptures, intricate metal castings at Ife, and an array of bronze and brass artifacts crafted by Yoruba artisans grace this cultural landscape.

Belief systems flourished in the Yoruba realms, presided over by a divine entity, a Lauren, and a host of minor deities entrusted with cosmic and practical roles. Among them, Oduduwa was revered as the creator of the earth and the forefather of the Yoruba kings. According to Yoruba mythos, Oduduwa founded the city of Ife and sent his sons to establish other cities where they reigned as priest-kings and directed cult rituals.

These myths have been seen as metaphorical narratives of the historical process through which Ife’s ruling dynasty exerted its influence over Yoruba land. The stories seek to legitimize the Yoruba monarchies by attributing them divine origins. Ife was the beating heart of over 400 religious cults, and the Oni cleverly used these traditions to strengthen his political standing during the kingdom’s golden era. Ife stood as a bustling hub of a vast trading network extending to the north. The Oni sustained his court through trade tolls, tributes from dependencies, and tithes collected as a religious leader. Ife’s most enduring legacy to modern Nigeria is its exquisite sculpture associated with this vibrant tradition.

The Oni, the ruler of the land, was chosen from the expansive branches of the ruling dynasty, a clan that boasted thousands of members. Once chosen, the Oni would retreat into the seclusion of the palace compound, forever hidden from the view of his people. Below him, palace officials, town chiefs, and rulers of external dependencies kept the kingdom running smoothly. These officials acted as the voice of the Oni and rulers of dependent territories, all of whom had their own chain of command.

Every office, including the Oni’s, required widespread community support. Officials were picked from clan members with a hereditary right to hold office. Members of the royal lineage were often tasked with governing dependencies, while the sons of palace officials took on secondary roles.

In the 15th century, Ife’s political and economic influence was overtaken by Oyo and Benin, although Ife retained its religious significance. The Oni of Ife’s priestly role and the shared origin story played a key part in shaping Yoruba ethnicity. The Oni of Ife held the highest political position recognized not only among the Yoruba but also in Benin, granting Benin’s rulers the symbols of their power.

The model of government established in Ife was adapted in Oyo, where a ruler brought several smaller city-states under his command. A state council, the Oyo Mesi, had the responsibility of choosing the Alaafin (king) from the proposed candidates from the ruling dynasty and acted as a balance to his authority. Unlike the Yoruba kingdoms nestled within the forest, Oyo was a savannah kingdom, gaining its strength from its cavalry forces, allowing it to expand its trade routes farther north.

To the east of Ife, an established agricultural community in the Edo-speaking area became a dependency of Ife in the early 14th century. By the 15th century, it had grown independent, becoming a major trading power. The king, or Oba, guided by a council of six hereditary chiefs, held political and religious power. At its zenith, Benin might have housed 100,000 inhabitants, spreading over 25 square kilometers within three rings of earthworks. The administration of this urban complex was handled by 60 trade guilds, each with its own neighborhood whose members were loyal to the Oba.

Unlike the Yoruba kingdoms, Benin developed a centralized system to manage its growing territories. By the late 15th century, Benin was trading with Portugal and, at its height, it even encompassed parts of southeastern Yoruba land and a small Igbo area on the western bank of the Niger. Dependencies were managed by royal family members scattered throughout the kingdom to prevent any rebellion against the Oba.

From this snapshot, it’s clear that the histories of Yoruba and Benin are entwined, extending even to the west of Nigeria into what is now the Republic of Benin. This relationship persisted both before and after the 1500s.

About the Creator

Balovic

Though I might be late, I never fail to make progress.

Comments (1)

Liked it. Well done!