Dark History UK: The Headless Child In Manchester

One of the city's most gruesome tales...

On 30th August 1832, John Hayes was living in a modest home on Silk Street in the Ancoats district of Manchester. That day, tragedy struck his household when its youngest member—his three-year-old grandson, John Brogan, for whom Hayes was guardian—was suddenly taken ill with the most feared disease of the age: cholera.

As the epidemic swept through the city, hope was scarce. Little John’s skin turned deathly pale, and his small body was wracked by violent spasms as the infection tightened its grip.

Desperate and terrified, his grandfather gathered the fading child into his arms and hurried to nearby Swan Street, where a cholera hospital had been established to cope with the rapidly spreading outbreak.

Tragically, just four hours later, little John Brogan was dead.

Later that evening, John’s body was taken to what had become known as the “Death House” — a temporary morgue where cholera victims were hastily prepared for burial in an effort to contain the spread of infection.

When a coffin was brought to receive the child, it was found to be far too small, and another had to be sent for. The delay meant that John’s burial did not take place until Sunday morning, at Walker’s Croft Cemetery.

When Sunday morning came, Hayes arrived to view his grandson’s body, only to discover that the coffin had already been sealed.

An unease he could not shake settled over him as he watched the hearse arrive at the cemetery, carrying not only John’s coffin but those of numerous other cholera victims.

It was as the coffins were being lifted down that Hayes noticed something deeply troubling: every one bore a nameplate—except the coffin said to contain his grandson’s body.

With this discovery, Hayes was seized by the certainty that something was terribly wrong. Refusing to accept that his grandson lay inside, he demanded that the coffin be opened—and, when refused, attempted to prise the lid free himself, to the horror of those gathered.

Onlookers pleaded with him to stop, calling his actions “disrespectful,” but Hayes would not be dissuaded. In his desperation, he clawed at the lid to no effect, until the reverend conducting the burials, moved by his anguish, agreed to help.

What was revealed when the coffin was finally opened was beyond imagining, and would soon provoke outrage across the city of Manchester.

Inside lay the mutilated body of the child—his head completely removed, a brick placed where it should have been.

As word spread through the town, residents flocked to the burial ground in their hundreds, eager to see whether the rumours were true. John Hayes lifted the coffin high and exposed the horrific sight of his grandson’s body to the crowd.

Shock gave way to fury as voices rose in a single, terrifying cry: “Burkers!”—a chilling reference to the Edinburgh body snatchers Burke and Hare, who had sold corpses to medical schools for profit.

The accusation hissed like venom from the crowd’s lips. Convinced that Manchester’s doctors had followed the same murderous path, suspicion hardened into a dangerous certainty: that the medical staff were killing for gain.

Suddenly, another scream cut through the crowd: “Burn the hospital!” The coffin was wrenched from Hayes’ grasp, hoisted aloft, and carried toward Swan Street Hospital.

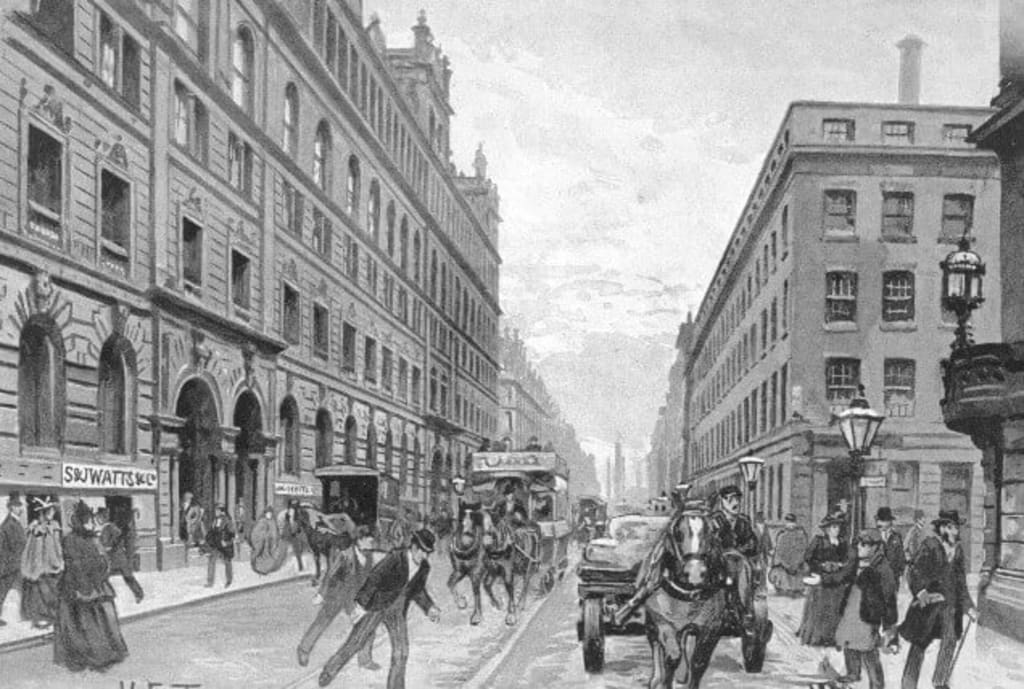

As the mob paraded the mutilated child’s body through the streets, their numbers swelled with every turn. Before long, some 3,000 enraged residents surged through Manchester, their fury feeding on itself.

Upon reaching Swan Street, the hospital gates were torn from their hinges and violence erupted. Windows were smashed, beds and chairs ripped apart, and a hospital van set ablaze.

Inside, the medical staff fled for their lives, convinced that if they remained, their blood would soon be spilled on the cobblestones.

As evening wore on, the reverend emerged to plead with the relentless crowd to disperse and return to their homes, but his appeals fell on deaf ears.

Soon after, the mob divided in two, and a new wave of rioting swept the streets. As they carried the child’s coffin onward, a terrible transformation took hold. What had begun as grief and a sense of righteous outrage curdled into something far more grotesque.

As the mob made its way toward Piccadilly—the very heart of the city—a handful of opportunists began collecting money from bystanders eager for a morbid glimpse of the headless child. What had once been driven by grief and fury now degraded into spectacle; the riot had become a grim means of profit.

When the crowd reached Piccadilly, a large detachment of special constables managed to scatter many of the rioters and seize the coffin. John Brogan’s remains were then taken under guard and transported to the town hall for safekeeping.

The child’s missing head was later discovered at the lodging house of Robert Oldham, a newly appointed hospital dispenser and the most likely culprit behind the decapitation. Despite an extensive search, Oldham had already fled. He was never seen again, and whether his actions were driven by morbid medical curiosity or the promise of financial gain was never conclusively established.

John’s head was wrapped in a handkerchief and conveyed to the town hall, where a surgeon sewed it back onto his body. The following day, the child’s funeral was held at St Patrick’s Church, and at last, John Brogan was laid to rest.

In the wake of the unrest, the city gradually returned to its daily routines, but the events surrounding John Brogan’s death left an indelible mark on Manchester’s history.

The fate of the little boy from Silk Street became a sombre reminder that in times of poverty, fear, and desperation, even the dead were not always permitted to rest in peace—and that the living would carry the scars long after the riots had faded into memory.

About the Creator

Matesanz

I write about history, true crime and strange phenomenon from around the world, subscribe for updates! I post daily.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.