The Pepsi 349 Scandal: How a Marketing Error Sparked Riots and Deaths in the Philippines

“Pepsi’s Number Fever Disaster: The Deadly 349 Promo That Shook the Philippines”

In 1992, PepsiCo launched an ambitious promotional campaign in the Philippines called "Number Fever" to boost its market share against Coca-Cola, which dominated with a 75% market share compared to Pepsi’s 17%. The campaign promised life-changing prizes, including a grand prize of one million pesos (approximately $40,000 USD), in a country grappling with widespread poverty. However, a catastrophic printing error turned this marketing stunt into a national crisis, leading to riots, at least five deaths, numerous injuries, and billions of dollars in potential liability. This article delves into the campaign’s mechanics, the error that sparked chaos, the violent fallout, and the long-term consequences for Pepsi in the Philippines.

The Number Fever Campaign

Pepsi’s "Number Fever" campaign, approved by the Philippine Department of Trade and Industry in January 1992, was designed to capitalize on the Filipino love for gambling and the allure of instant wealth. The mechanics were straightforward:

How It Worked: Bottle caps (or "crowns") of Pepsi, 7-Up, Mountain Dew, and Mirinda had three-digit numbers (001 to 999) printed inside, along with a prize amount ranging from 100 pesos ($4 USD) to one million pesos ($40,000 USD). A security code was included to verify winning caps.

Daily Announcements: Each night, the winning number was announced on Channel 2’s news program. Most prizes were small, but the grand prize of one million pesos was a life-changing sum, equivalent to 611 times the average monthly salary in the Philippines at the time.

Initial Success: The campaign was a hit, boosting Pepsi’s sales by nearly 40% and increasing its market share to 24%. Over 31 million Filipinos—half the country’s population—participated, with 51,000 winning smaller prizes and 17 claiming the grand prize by May 1992.

Pepsi allocated $2 million USD for prizes, working with a Mexican consultancy, D.G. Consultores, to preselect winning numbers. These numbers were secured in a Manila safe deposit box, and winning caps were seeded at bottling plants with corresponding security codes to prevent fraud.

The Catastrophic Error

On May 25, 1992, disaster struck. The ABS-CBN evening news announced the grand prize-winning number: 349. An estimated 70% of the Philippines’ 65 million people were watching, eager to check their bottle caps. However, a computer glitch at a bottling plant had caused a monumental error: instead of just two winning caps with the number 349 and a security code, 800,000 regular caps had been printed with the number 349 but without the security code. These caps were theoretically worth $32 billion USD if redeemed at the grand prize value.

The next morning, thousands of Filipinos, believing they were millionaires, flooded Pepsi bottling plants to claim their prizes. Pepsi quickly announced that the 349 caps without security codes were invalid, citing the error. To make matters worse, newspapers mistakenly reported the winning number as 134 the following day, adding to the confusion. The public, already distrustful of large corporations, felt cheated. For many, the promise of a million pesos had been a beacon of hope in a struggling economy.

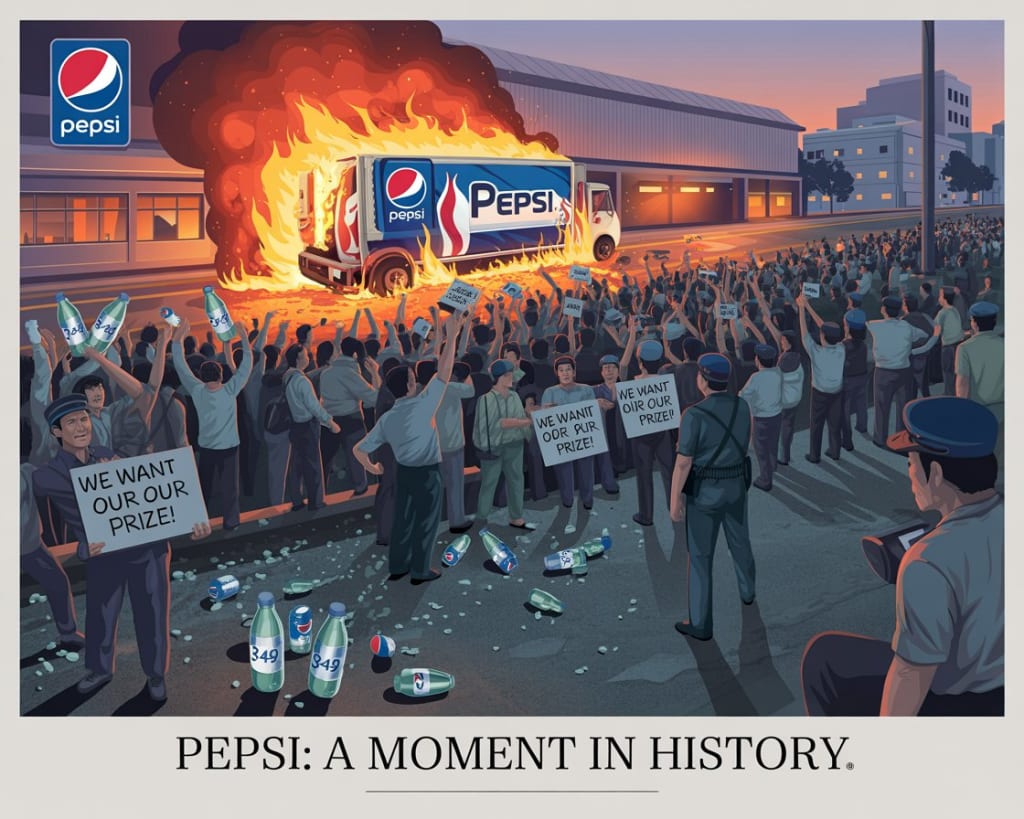

The Violent Aftermath

The announcement that 800,000 "winners" would not receive their prizes sparked outrage. The fallout was swift and violent:

Protests and Riots: Furious consumers formed the "349 Alliance," a group that organized boycotts and rallies outside Pepsi offices and government buildings. While most protests were peaceful, some escalated into violence. Over 35 Pepsi delivery trucks were overturned, stoned, or burned. Molotov cocktails and homemade bombs were thrown at Pepsi plants and offices.

Deaths and Injuries: At least five people died in incidents linked to the protests. On February 13, 1993, a homemade bomb thrown at a Pepsi truck in Manila bounced off and killed a schoolteacher and a 5-year-old girl, injuring six others. In May 1993, a grenade attack on a Pepsi warehouse in Davao killed three employees. Numerous other injuries were reported during riots.

Executive Safety Concerns: Pepsi executives received death threats, prompting the company to hire round-the-clock bodyguards and arm guards on delivery trucks. Most expatriate staff were withdrawn, leaving a manager with experience in Beirut to handle the crisis.

Pepsi’s response was to offer a "goodwill gesture" of 500 pesos ($18-$20 USD) to each 349 cap holder, costing the company $10 million USD—five times the original prize budget. While some accepted the payment, many rejected it, feeling it was inadequate compared to the promised million pesos.

Legal and Political Repercussions

The scandal triggered a massive legal and political backlash:

Lawsuits: Approximately 22,000 people filed 689 civil suits and 5,200 criminal complaints against Pepsi for fraud and deception. One group, Ugnayan 349, demanded compensation through the courts. In 1996, a trial court awarded 10,000 pesos ($380 USD) per plaintiff in one case for "moral damages." Appeals continued, and in 2006, the Philippine Supreme Court ruled that Pepsi was not liable to pay the amounts printed on the caps, citing no proof of negligence.

Government Response: The Philippine Senate Committee on Trade and Commerce accused Pepsi of "gross negligence," noting a similar error in a Chilean promotion a month earlier. Pepsi paid a 150,000-peso fine to the Department of Trade and Industry for violating the promotion’s conditions.

Conspiracy Theories: A police officer alleged that Pepsi orchestrated the bombings to frame protesters as terrorists, though this claim was never substantiated. Then-Senator Gloria Macapagal Arroyo suggested rival bottlers might have exploited Pepsi’s vulnerability.

The legal battles dragged on for over a decade, with some cases dismissed as late as 2007. The scandal also led to stricter regulations for promotional contests in the Philippines.

Impact on Pepsi and Public Sentiment

The "Number Fever" debacle had profound consequences for Pepsi in the Philippines:

Market Share and Sales: Pepsi’s market share plummeted to 17% in the immediate aftermath, though it recovered to 21% by 1994. However, the brand became taboo for many Filipinos. Some, like Manila store owner Marily So, refused to sell Pepsi decades later, harboring resentment from the broken promises.

Reputation Damage: The scandal cemented Pepsi’s image as a callous multinational in the eyes of many Filipinos. The phrase "349ed" entered the local lexicon, meaning to be tricked or cheated.

Cultural Legacy: The fiasco was commemorated with the 1993 Ig Nobel Peace Prize, awarded to Pepsi for "bringing many warring factions together" in protest. It was also referenced in the 2022 Netflix documentary Pepsi, Where’s My Jet? as a precedent for false advertising lawsuits.

Lessons Learned

The Pepsi 349 incident remains a cautionary tale for marketers worldwide. Key takeaways include:

Robust Oversight: The failure to double-check the printing process and security code distribution was a critical oversight. Companies must ensure foolproof systems for high-stakes promotions.

Cultural Sensitivity: Pepsi underestimated the emotional and economic significance of the million-peso prize in a poverty-stricken nation, amplifying public outrage when the error was revealed.

Crisis Management: Pepsi’s initial refusal to honor the caps and its delayed goodwill gesture fueled perceptions of corporate greed. Transparent and empathetic crisis management could have mitigated the backlash.

Conclusion

Pepsi’s "Number Fever" campaign was intended to be a bold move to challenge Coca-Cola’s dominance in the Philippines. Instead, a single printing error—number 349—unleashed a cascade of chaos, violence, and legal battles that cost Pepsi millions and tarnished its reputation for decades. The tragedy of five deaths and numerous injuries underscores the real-world consequences of marketing gone wrong. The 349 incident serves as a stark reminder that even the most well-intentioned campaigns can spiral into disaster without meticulous planning and execution.

About the Creator

Doctor Strange

Publisher and storyteller on Vocal Media, sharing stories that inspire, provoke thought, and connect with readers on a deeper level

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.