The Grisly Death Of ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’

The real life tale of one of the most haunting murder cases from the late 1800s.

Born on 30th April 1859 in the small market town of Alton, England, Fanny Adams had lived with her family on Tanhouse Lane.

The 1861 census shows that Fanny lived with her mother, father and five siblings. The family were apparently locally rooted; George Adams and his wife Ann, believed to have been Fanny’s grandparents, lived next door.

Fanny was described as a “tall, comely, and intelligent girl.” She appeared older than her true age of eight and was well known locally for her lively, cheerful disposition. Her closest friend, Minnie Warner, was the same age and lived just two doors away from her.

Although the family was by no means wealthy, Fanny’s life as the daughter of an agricultural labourer was simple but secure; she was adequately fed, clothed, and clearly loved.

During the nineteenth century, Alton had experienced little serious crime and was regarded as a particularly safe place to live. As a result, parents felt little cause for concern about allowing their children to play freely around the town. One of the most popular and enjoyable places for local children was the nearby Flood Meadows.

The afternoon of 24th August 1867 was reported to be fine, sunny, and hot. On that day, Fanny, accompanied by her sister Lizzie and her best friend Minnie Warner, asked their mother, Harriet Adams, for permission to visit the nearby Flood Meadow. Fanny’s father was planning to play cricket later in the day, while Harriet was occupied with caring for the younger children and attending to household chores.

Seeing no reason to object—and glad of some respite while she continued with her work—Harriet agreed, and the three young girls set off on the short walk. Along the way, however, they encountered Frederick Baker, a 29 year old solicitor’s clerk whom they recognised from church.

Baker had moved from Guildford to Alton approximately twelve months earlier, having taken up employment with the solicitor Mr Clements. His office was located on Alton High Street, opposite the Swan Hotel, an establishment that Baker was known to frequent.

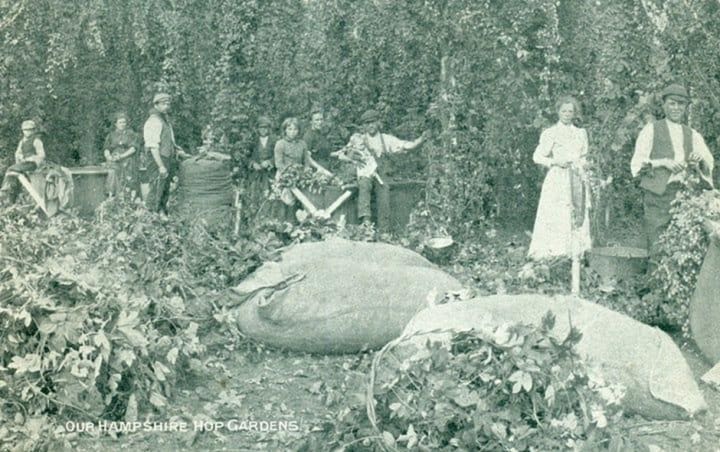

Although the children suspected that Baker had been drinking, they nevertheless believed him to be a respectable man. The girls were content to stop and speak with him, and he gave Minnie and Lizzie three halfpence to spend on sweets, offering Fanny an additional halfpenny if she would accompany him into a nearby hop garden. All three accepted the money, but Fanny remained close to her sister and friend.

For a time, the children played happily in the Flood Meadows, while Baker lingered nearby picking blackberries, which he offered to them. During this period, he made no overt move towards Fanny. After an hour or so, however, Lizzie and Minnie, now tired, hot, and hungry, decided to return home.

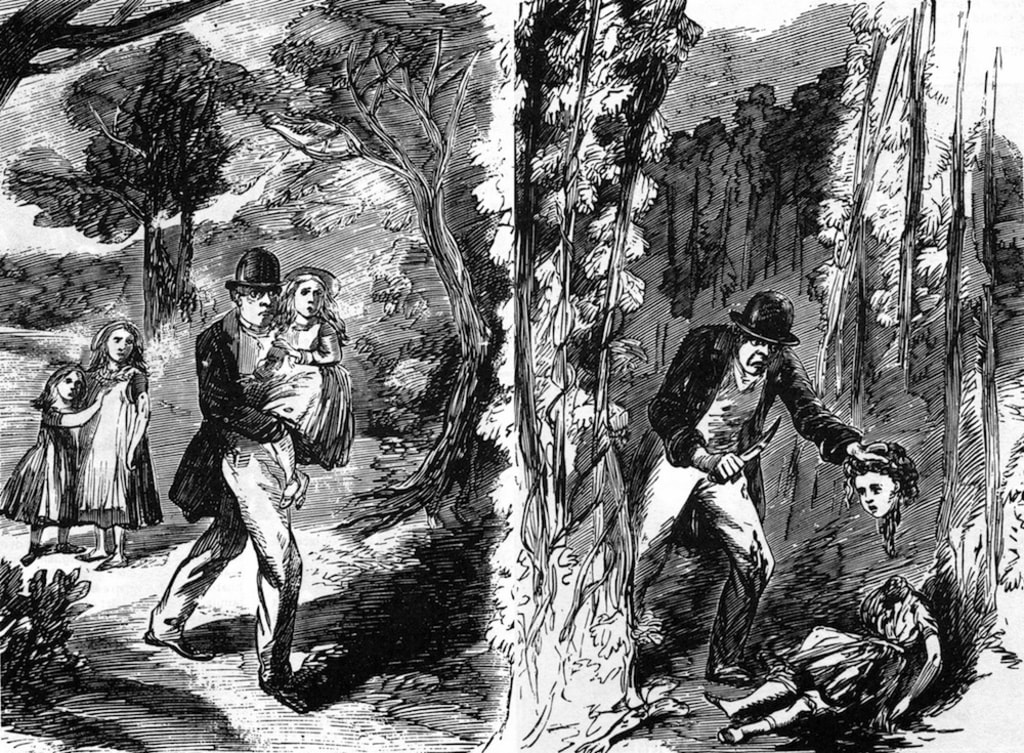

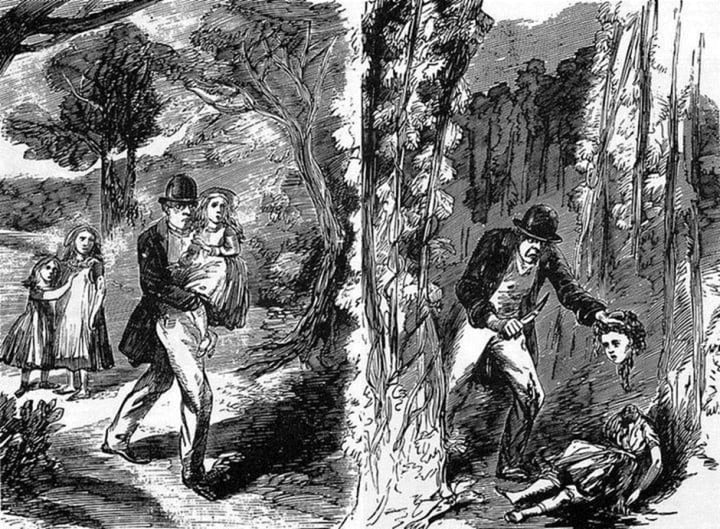

As they prepared to leave, Baker suddenly intercepted them and asked Fanny to go with him to the neighbouring village of Shalden. When she refused, he seized the screaming child and dragged her into a nearby hop garden.

Terrified by what they had witnessed, the two girls ran as fast as they could to Minnie’s home and reported the abduction to her mother, Martha Warner. Dismissing their account as childish imagination, she sent them away to continue playing.

It was not until five o’clock that afternoon, when Minnie repeated the story to a neighbour, Mrs Gardner, that serious concern arose and the search for Fanny finally began. Alarmed by what she heard, Mrs Gardner immediately sought out Fanny’s mother, Harriet Adams, and together the two women set off towards the Flood Meadows to look for the missing child.

As they neared the meadows, they encountered Frederick Baker. According to one contemporary account, the exchange between Harriet Adams and Baker unfolded as follows:

Perhaps intimidated by Baker’s position and his air of confidence, the two women accepted his explanation and returned home, hoping that Fanny would soon reappear.

By between seven and eight o’clock that evening, however, Fanny had still not returned. Growing increasingly anxious, Harriet Adams and a group of neighbours set out once more to search for the missing child. Their efforts proved fruitless; Fanny was nowhere to be found in the Flood Meadows or along the lane known as the Hollows, which led towards Shalden.

It was only when a local labourer, Thomas Gates, entered a nearby hop garden to tend his crop that the grim truth came to light. There, he stumbled upon a horrific scene.

Positioned upon two hop poles was the severed head of the missing child. One of Fanny’s ears had been cut away, and deep wounds ran from her mouth towards her temple.

Not only had poor Fanny's head been removed, but her body and internal organs had been dismembered and strewn about the area.

There were three incisions on the left side of her chest, and a deep cut on her left arm, dividing her muscles. Fanny’s forearm was cut off at the elbow joint, and her left leg nearly severed off at the hip joint, with her left foot cut off at the ankle point.

Her right leg was torn from the trunk, and the whole contents of her pelvis and chest were completely removed. Five further incisions had been made on the liver. Her heart had been cut out, and her vagina was missing. Both of her eyes were cut out, and found in the nearby River Wey.

Overcome with grief, Harriet Adams collapsed while on her way to inform her husband, George, who was playing cricket at the time. As she was unable to reach him herself, word was sent instead.

When George Adams learned what had happened, he returned home, took his loaded shotgun, and set out in search of the perpetrator. Neighbours, fearing the consequences of such an act, intervened and persuaded him to remain at home, where they sat with him throughout the night.

The following day, hundreds of local people descended upon the hop garden to assist in the grim task of recovering Fanny’s scattered remains. Police searches for the murder weapons proved unsuccessful, though it was believed that small knives had been used. Officers did, however, recover all of Fanny’s severed clothing, which was found strewn across the field, with the sole exception of her hat.

Most of Fanny’s remains were gathered that day, though an arm, a foot, and portions of her intestines were not discovered until the following morning. One foot was still encased in its shoe, and clutched in one small hand were the two halfpence Baker had given her. The breastbone was never recovered.

Fanny’s remains were taken to the doctor’s surgery on Amery Street, where a post-mortem examination was conducted. The building was later converted into a public house known as Ye Olde Leathern Bottle and has since become a private residence.

Fanny’s remains were sewn together only yards from her family home.

Meanwhile, police set out to locate Frederick Baker, who had gone to work as usual at the solicitor’s offices in Alton. He was arrested there on suspicion of murder. When searched, Baker was found to be carrying two small knives. Small spots of blood were visible on the cuffs of his shirt, though not in quantities sufficient to suggest the violent dismemberment of a child.

Baker’s colleagues at the solicitor’s office later became crucial witnesses. Their testimony helped investigators reconstruct his movements on the day of the murder, revealing suspicious absences and a series of unsettling remarks, including a macabre joke that he might find new employment as a butcher.

In a diary later discovered on his desk, Baker had recorded an entry for Saturday, 24th August 1867, stating: “Killed a young girl. It was fine and hot.”

By this time, a large and agitated crowd had gathered outside the solicitor’s office, forcing the police to smuggle Baker out the back door for fear that the mob would take matters into their own hands.

When questioned about his appearance, Baker reportedly said: “Well, I don’t see a scratch or cut on my hands to account for the blood.”

Observers described his conduct during the interrogation as calm and composed. He remained completely unfazed by the murder and displayed no signs of insanity or remorse.

A local painter, William Walker, came forward with a large stone he had found in the hopfield, which was covered in blood, strands of long hair, and a small fragment of flesh. Dr. Louis Leslie, the Alton divisional police surgeon, concluded in his post-mortem analysis that Fanny’s cause of death was 'massive blunt force trauma from a blow to the head,' and that the stone was likely the murder weapon.

An eyewitness statement from a young child soon emerged. The child reported seeing Baker leaving the hop garden where Fanny had been found, covered in blood, and stopping to wash himself in a nearby pond.

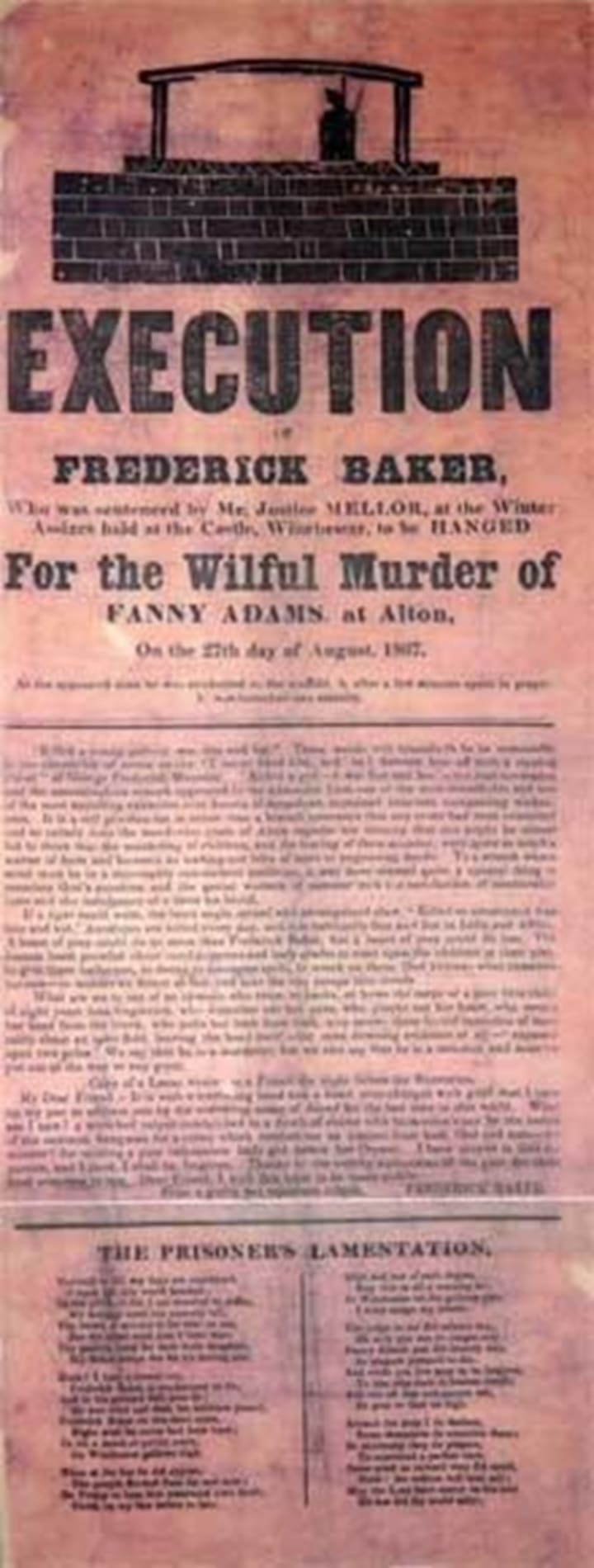

On 5th December 1867, Baker stood trial for Fanny’s murder. Throughout the proceedings, he denied any involvement in the crime. His defence counsel, however, argued that Baker was insane, citing a family history of mental illness: his father had reportedly shown violent tendencies, including towards his own children; a cousin had been institutionalised four times; his sister had died of ‘brain fever’; and Baker himself had previously attempted suicide following an unrequited love affair.

Despite these claims, the jury returned a verdict of wilful murder, finding Frederick Baker guilty of killing Fanny Adams.

On 24th December, Christmas Eve, Frederick Baker was hanged outside Winchester Prison. The case had become notorious, and a crowd of approximately 5,000 people gathered to witness the execution. This marked the last public execution to be held at the prison.

Before his death, Baker wrote to the Adams family, expressing sorrow for what he had done “in an unguarded hour” and seeking their forgiveness.

The night before his execution, he penned a letter to a friend:

He concluded the letter with the signature:

Following his execution, a death mask of Baker was made, and the following year his full figure was displayed as an exhibit in the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussauds’ famous waxworks in London.

Fanny was laid to rest in Alton Cemetery. Determined that she should not be forgotten, the local community raised funds for a headstone, which still stands today at her gravesite.

The inscription reads:

About the Creator

Matesanz

I write about history, true crime and strange phenomenon from around the world, subscribe for updates! I post daily.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.