Fossils show how the Caribbean reef ecosystems were drastically altered by humans.

These species appear to have become smaller and more mature early as a result of overfishing.

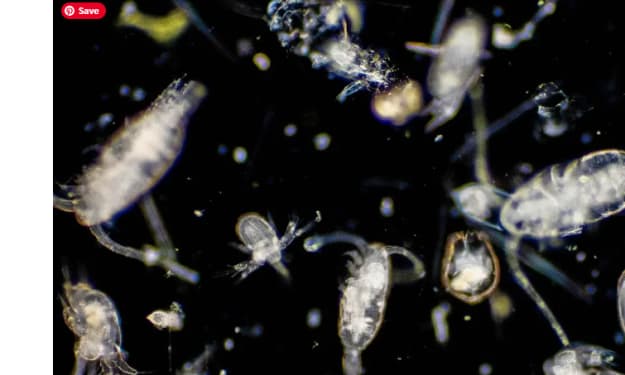

We frequently envision dinosaurs when we think of fossils. However, reefs can also have a long history. In these environments, tiny fish bones and shark scales also turn into fossils, subtly telling the tale of past seas.

Humans have already disturbed Caribbean reefs, according to a startling study from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI). Scientists examined fossilised coral reefs from the Dominican Republic and Bocas del Toro in Panama. These well-preserved, exposed reefs are 7,000 years old.

Communities of reef fish were altered by humans.

In order to demonstrate how overfishing altered fish ecosystems, the researchers contrasted the fossilised reefs with adjacent living reefs. The scientists discovered thousands of fossilised otoliths (fish ear bones) and dermal denticles (shark scales) in the ancient reef sediments.

The size and makeup of the species were inferred from these fossils. The findings reveal a significant change in predator-prey dynamics that has never been observed before.

A 75% decrease in shark populations was one of the most concerning results. In the past, these top predators were essential to preserving the equilibrium of the reef. Prey fish populations increased as their numbers decreased. They multiplied by twofold.

The effect of predator release

Hard evidence for the "predator release effect" is provided by the study. Although scientists had long anticipated this result, they needed reliable prehistoric evidence to support their theory. The fossils now support what models previously predicted: the removal of predators causes prey populations to soar.

In the meantime, human-targeted fish, such as larger groupers and snappers, shrank by 22%. This tendency of shrinkage is consistent with current observations. These species appear to have become smaller and more mature early as a result of overfishing.

Some fish don't change.

A separate scenario was revealed by the remains of little cryptobenthic reef fishes, which reside in the cracks of coral. Over thousands of years, they did not vary in size or abundance. These reef inhabitants remained steady in the face of fishing and disturbance above. The researchers were taken aback by their toughness.

The researchers observed, "The stability of these fish demonstrates remarkable resistance to external pressures." These concealed species persisted unaltered despite the disappearance of top predators and increased fishing.

The researchers analysed 5,724 otoliths and 807 shark denticles to quantify these changes. They also looked for signs of damselfish bites on coral branches. Damselfish bite more frequently now, according to fossil and contemporary samples, most likely as a result of fewer predators.

Large reef changes are revealed by fish bones.

Like tree rings, otoliths grow in layers. This enables researchers to determine the size and age of fish at the moment of death. Researchers could monitor size variations over millennia by contrasting fossil and contemporary otoliths.

Shark presence was identified with the aid of dermal denticles, which are scale-like features on shark skin. These small details reveal a significant trend: prey species populations increased as shark populations declined.

Damselfish bite marks also provided information. These feisty, tiny fish leave noticeable marks and defend their territories. Another indication of the consequences of predator loss is the fact that more bites currently translate into more damselfish.

Using fossils to trace the evolution of reef fish

Scientists have a unique and useful baseline because of this fossil evidence. It depicts the appearance of Caribbean reef fish communities before the structural changes brought about by human fishing.

Conservation efforts frequently rely on recent or insufficient data that do not capture the whole picture of ecological change in the absence of such deep-time context.

Researchers and reef managers can now plainly observe which aspects of the reef ecosystem changed as a result of human activity, while other elements, such as little fish that live on reefs, stayed constant throughout thousands of years. The researchers said, "This study demonstrates the power of the fossil record for future conservation."

Effects of human activity across time

We can better understand the long-term effects of human activity on fish sizes, predator-prey dynamics, and reef food webs thanks to these 7,000-year-old fossils. They also assist in determining which reef interactions and species are most vulnerable to ongoing stress.

Scientists can make better decisions about reef conservation, fishing regulations, and biodiversity management today by using the fossil record to look back in time.

The Centre for Biodiversity Outcomes at Arizona State University, the Marine Science Institute at the University of Texas, Austin, and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) collaborated on the study.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.