"Spurn Fate, Scorn Death"

An Analysis of Shakespeare Through Seneca

Background and Context:

If I've said it once, I've said it a million times - most of the readings for these essays come from things I did on my degree. Please, try to read the secondary sources if you're interested. There's a lot of great stuff in there! (If you want to be pointed in the direction of which are the best then please, do not hesitate to get into contact. I love sharing this stuff about Shakespeare).

If you would like to check out my other Shakespeare essays based on plans and titles that were coined but never written from my university days, then take a look at the following list:

Instruments of Darkness: Gothic Tropes in Shakespeare's Plays

All the World's a Stage: Shakespeare's Theatrical Exploration of the Human Condition

"Spurn Fate, Scorn Death"

An Analysis of Shakespeare Through Seneca

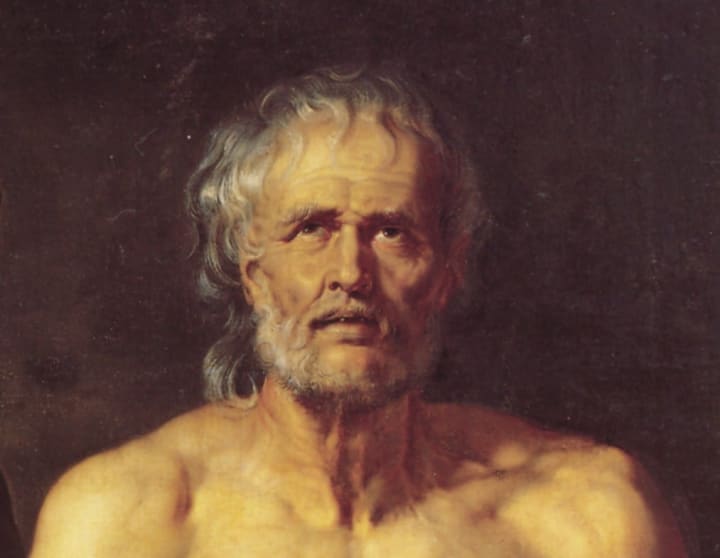

Lucius Annaeus Seneca, a Stoic philosopher and playwright, was a central figure in the writing of Roman tragedy. His works, often marked by their intense emotions, moral dilemmas, and philosophical underpinnings, played a significant role in the shaping of Renaissance drama. Seneca’s tragedies were characterised by: revenge, fate, and the supernatural, using a style that involved rhetorical speeches, moral lessons, and extreme emotional responses. These elements had a great impact on the playwrights of the Renaissance (which revisited the classical era writings), particularly William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare, known for his ability to adapt and transform various classical influences, drew heavily on Seneca’s dramatic conventions. The use of soliloquies, heightened emotional states, supernatural elements, and themes of revenge and fate in Shakespeare’s tragedies can be traced back to Seneca’s influence. However, Shakespeare did not merely replicate these elements; instead, he integrated them into his own distinct dramatic style, blending them with his exploration of complex human nature, psychological depth, and moral ambiguity.

As Colin Burrow states in Shakespeare and Classical Antiquity, Shakespeare’s relationship with classical models was not one of mere imitation, but of re-interpretation, where he both honoured and transformed the classical legacy. In doing so, Shakespeare developed a tragedy genre that was uniquely his own, influenced by Seneca but marked by a profound philosophical and dramatic sophistication.

Dramatic Form and Structure

Seneca’s tragedies, written in the 1st century AD, established a distinct model of dramatic structure and thematic focus that would later influence the Renaissance playwrights. These tragedies, notably Phaedra, Thyestes, and Medea, are characterised by their intense emotions, rhetorical speeches, and philosophical underpinnings, especially the Stoic notion of fate and revenge. One of the most striking features of Seneca’s work is the prominent use of soliloquies and long monologues that allow characters to express their inner turmoil, philosophy, and desires. This element of self-reflection and introspection, integral to Seneca's style, became an important device in Shakespeare's own tragedies.

Also, Seneca's tragedies typically involve supernatural elements, such as gods or omens, which drive the action or reveal the fate of the characters. These elements are tied to a central moral lesson or philosophical reflection on power, revenge, and the human condition. The five-act structure, which became standard for later Western theatre, was also a feature of Seneca’s plays, though this was a pattern likely influenced by both his classical predecessors and the Roman theatre. Seneca often employed a chorus to comment on the unfolding events, adding a layer of moral reflection and commentary on the action. While the chorus did not play as central a role in Shakespeare's plays, the idea of an external commentary on the unfolding drama is still present, albeit through various other forms.

Shakespeare’s use of Senecan techniques in his own tragedies can be seen most clearly in plays such as Hamlet and Titus Andronicus. A key Senecan feature that Shakespeare adopted is the soliloquy. In Hamlet, for example, the protagonist’s introspective soliloquies allow the audience to access his philosophical musings on life, death, and moral action. Hamlet’s famous “To be, or not to be” soliloquy mirrors the intense self-examination found in Seneca’s tragic figures, such as Medea and Thyestes, who are given long monologues to express their inner conflict and motivations (Gibson, 2004). Shakespeare, however, extends this technique by embedding a deeper psychological complexity, exploring not only moral dilemmas but also the intricacies of human consciousness and the difficulty of decision-making in a corrupt world.

Seneca’s emphasis on revenge is another key aspect of his tragedies that Shakespeare incorporated into his works. Revenge is a central theme in Titus Andronicus, where the title character embarks on a brutal quest for vengeance against those who have wronged him. This play, much like Seneca’s Thyestes or Phaedra, is marked by extreme violence and moral ambiguity. In both Shakespeare and Seneca, revenge is portrayed as a destructive force, often leading to the moral degradation of the avenger.

For example, Titus’s pursuit of revenge leads him down a dark path, where his own actions become as morally questionable as those of his enemies, much like Seneca’s characters who, consumed by vengeance, often descend into madness or destruction. Similarly, in Hamlet, the Prince’s contemplation of revenge is laden with hesitation and reflection, but ultimately the drive for vengeance propels the tragic action forward, much as it does in Seneca’s tragedies. While Shakespeare’s revenge plays are more subtle than Seneca’s, with their exploration of moral consequences and the complexities of human emotion, the influence of Seneca’s straightforward and rhetorically charged approach to vengeance is clear.

Seneca's Characters vs. Shakespeare's Characters

Seneca’s Stoic philosophy, which emphasises self-control, rationality, and endurance in the face of suffering, plays a significant role in shaping the moral and psychological dimensions of Shakespeare’s characters. As a philosopher, Seneca advocated for the mastery of emotions through reason, arguing that true virtue lay in maintaining composure amid hardship. His tragedies, however, often depict characters who struggle between their Stoic ideals and the overpowering forces of passion, revenge, or fate. This paradox of emotional turmoil within a framework of rational philosophy is one that Shakespeare also engages with in his tragedies. As Colin Burrow notes, Shakespeare was deeply influenced by Seneca’s moral and philosophical outlook, incorporating elements of Stoicism into the minds of his tragic heroes while simultaneously questioning their efficacy in real-world dilemmas (Burrow, 2007).

One of Shakespeare’s most explicitly Stoic characters is Marcus Brutus in Julius Caesar. A self-professed follower of Stoicism, Brutus attempts to maintain rationality and moral integrity even as he becomes embroiled in the conspiracy against Caesar. His famous speech, “Not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved Rome more” (III.ii.21-22), reflects a Senecan emphasis on duty over personal emotion. Brutus, like Seneca’s characters, seeks to rationalise his actions within a philosophical framework, convincing himself that he is acting for the greater good rather than personal ambition. Yet, much like Seneca’s tragic figures, Brutus’s Stoicism ultimately proves insufficient in shielding him from the emotional consequences of his decisions. He is haunted by guilt, personal loss, and the spectre of Caesar’s ghost, illustrating Shakespeare’s engagement with the limitations of Stoic philosophy when confronted with human frailty (Reynolds, 2018).

Similarly, Horatio in Hamlet embodies many Stoic qualities. As Hamlet’s loyal friend, he remains composed and rational amidst the chaos of Elsinore. Unlike Hamlet, who is plagued by indecision, philosophical doubt, and emotional instability, Horatio maintains his calm and serves as a grounding presence. His measured reaction to the appearance of the ghost contrasts sharply with Hamlet’s intense existential questioning. In the final act, when Hamlet is dying, Horatio attempts to follow the Stoic ideal stating, “I am more an antique Roman than a Dane” (V.ii.341), alluding to the Roman Stoic tradition of honourable sacrifice. However, Hamlet persuades him to live, reinforcing Shakespeare’s tendency to challenge Stoic ideals rather than simply endorsing them.

In contrast to Horatio and Brutus, Shakespeare’s more emotionally volatile characters, such as Hamlet himself, reflect a key distinction from Seneca’s tragedies. While Seneca’s characters often experience extreme emotional states, they tend to rationalise their actions through philosophical justification, as seen in Medea, who intellectualises her vengeful rage. Hamlet, however, wrestles with emotions in a way that is far more psychologically intricate, vacillating between Stoic detachment and emotional outbursts. His famous soliloquies expose a depth of self-reflection and inner conflict that extends beyond Seneca’s rhetorical monologues, illustrating Shakespeare’s innovation in depicting internal struggles (Gibson, 2004).

Ultimately, Shakespeare’s engagement with Stoicism reveals both its strengths and its limitations. While characters like Brutus and Horatio embody its ideals, their fates suggest that Stoic detachment is not always an adequate response to the complexities of human experience. By incorporating and interrogating Seneca’s Stoic philosophy, Shakespeare deepens the moral and psychological complexity of his tragic figures, demonstrating a greater understanding of the unpredictability of human nature.

The Supernatural and Fate

Seneca’s tragedies frequently incorporate supernatural elements such as ghosts, omens, and prophecies, serving as instruments of fate and moral retribution. These supernatural occurrences not only heighten dramatic tension but also reinforce the inescapable consequences of human actions. Shakespeare integrates similar elements into his own tragedies, where ghosts, witches, and prophetic visions shape the fates of his protagonists. However, while Seneca’s supernatural figures often serve as external manifestations of fate’s inevitability, Shakespeare complicates their role by intertwining them with his characters’ psychological states. As Colin Burrow observes, Shakespeare did not simply adopt classical tropes but reworked them in ways that deepened his plays’ moral and existential concerns (Burrow, 2007).

One of the most direct examples of Seneca’s influence can be seen in the ghost of King Hamlet in Hamlet. Much like the spectral apparitions in Seneca’s Thyestes, who foreshadow doom and vengeance, King Hamlet’s ghost appears as an agent of supernatural justice, urging his son to seek retribution for his murder. The ghost’s opening words, “I am thy father’s spirit, / Doomed for a certain term to walk the night” (I.v.9-10), establish its role as both a harbinger of fate and a moral arbiter. In Seneca’s tragedies, ghosts typically serve to expose hidden crimes and set the tragic cycle in motion, as seen in Thyestes, where the ghost of Tantalus appears to curse the house of Atreus. Similarly, Hamlet’s ghost functions as the catalyst for the play’s revenge plot, reinforcing the Senecan notion of fate as an inexorable force (Miola, 1992). However, Shakespeare’s innovation lies in Hamlet’s scepticism, unlike Senecan characters who often accept supernatural messages without question, Hamlet grapples with doubt, contemplating whether the ghost is truly a messenger of fate or a demonic deception (II.ii).

Another striking example of Seneca’s supernatural influence is found in Macbeth, particularly in the role of the witches. Seneca’s tragedies frequently employ prophetic visions and omens to foreshadow disaster, as seen in Oedipus, where Tiresias’s prophecies reveal the protagonist’s doomed fate. Similarly, the witches’ cryptic declarations in Macbeth, beginning with “All hail, Macbeth! Hail to thee, Thane of Glamis! / Hail to thee, Thane of Cawdor! / Hail to thee, that shalt be king hereafter!” (I.iii.48-50), manipulate Macbeth’s perception of destiny. Like Seneca’s characters, Macbeth becomes ensnared in a self-fulfilling prophecy, interpreting supernatural signs in a way that fuels his own ambition and descent into tyranny. However, while Seneca’s omens often serve as unambiguous indicators of fate, Shakespeare introduces ambiguity: do the witches dictate Macbeth’s fate, or does he shape his own downfall through free will? This refined treatment of supernatural influence sets Shakespeare apart from his classical predecessor (Braunmuller, 1997).

By adopting and reimagining Seneca’s use of the supernatural, Shakespeare deepens the thematic complexity of his tragedies. Whereas Seneca’s ghosts and omens often serve as external manifestations of fate, Shakespeare’s supernatural elements engage more profoundly with the psychological dilemmas of his characters. The ghost in Hamlet and the witches in Macbeth function as eerie reflections of their protagonists’ inner conflicts, blurring the boundaries between fate and free will. Through these supernatural figures, Shakespeare not only honours Seneca’s dramatic conventions but also challenges and reinterprets them, demonstrating his ability to transform classical influences into his own distinct vision of tragedy.

Violence and Revenge

Seneca’s tragedies are deeply preoccupied with revenge, often portraying it as an all-consuming force that leads to extreme violence and destruction. His works, such as Thyestes and Medea, depict revenge as both inevitable and excessive, frequently culminating in acts of grotesque brutality. Senecan revenge is characterised by a relentless pursuit of justice (or retribution) where the avenger is often as corrupted as their victim. Shakespeare, while influenced by Seneca’s treatment of revenge, develops a more profound exploration of its moral implications. In plays like Hamlet and Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare retains the brutal violence of Seneca but complicates the ethical dimension, forcing his characters to grapple with the consequences of their actions. As Robert S. Miola argues, Shakespeare “absorbed and transformed Seneca’s tragedies, refining their themes and deepening their psychological complexity” (Miola, 1992).

One of the clearest manifestations of Seneca’s revenge motifs in Shakespeare’s work is found in Hamlet. The play shares significant structural and thematic similarities with Senecan revenge tragedies, particularly in its use of soliloquies, ghosts as agents of vengeance, and the hero’s prolonged deliberation before enacting revenge. Like Seneca’s avengers, Hamlet is driven by the need to right a profound wrong: the murder of his father. However, unlike Senecan protagonists, who often embrace vengeance without hesitation, Hamlet wrestles with moral doubt. His hesitation and philosophical introspection, particularly in the “To be or not to be” soliloquy (III.i.56-88), contrast with the single-minded determination of Senecan figures such as Medea or Atreus. As Colin Burrow notes, “Shakespeare engages with Seneca not by mere imitation, but by deepening the psychological realism of his tragic protagonists, making their dilemmas more complex and their choices less clear-cut” (Burrow, 2007).

Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus offers a much more overt homage to Senecan revenge tragedy. The play’s excessive violence: Titus cutting off his own hand, Lavinia’s mutilation, and the infamous act of baking Tamora’s sons into a pie, mirrors the grotesque brutality found in Seneca’s Thyestes, where Atreus serves his brother a feast made from his own children. However, while Seneca’s Thyestes presents revenge as a cyclical force of destruction, Shakespeare introduces moments of tragic awareness. Titus, though initially an agent of revenge, ultimately becomes a victim of its uncontrollable momentum. His descent into madness suggests that revenge, rather than being a path to justice, leads only to chaos and annihilation. In this way, Shakespeare problematises Seneca’s model, showing the psychological and ethical costs of vengeance rather than merely its execution (Bowers, 1959).

A key distinction between Seneca and Shakespeare lies in their treatment of revenge as a moral concept. Seneca’s plays often depict revenge as an inevitable duty, closely tied to fate and the gods’ will. Shakespeare, however, complicates this notion by presenting revenge as morally ambiguous. In Hamlet, the protagonist questions whether vengeance is truly justified, while in Titus Andronicus, the cycle of retribution ultimately destroys all involved. Unlike Seneca, whose characters rarely question the righteousness of their revenge, Shakespeare explores the emotional and ethical turmoil that accompanies acts of retribution. As Bowers asserts, “Shakespeare’s tragedies do not simply echo Seneca’s bloodshed; they interrogate it, presenting revenge as a dilemma rather than a certainty” (Bowers, 1959).

Through his engagement with Seneca’s treatment of revenge, Shakespeare retains the dramatic intensity of Roman tragedy while expanding its philosophical and psychological depth. His plays do not merely copy Seneca’s violent spectacles; rather, they challenge and reinterpret them, transforming revenge from an unquestioned duty into a source of existential crisis. This exploration of vengeance is what distinguishes Shakespeare’s tragedies from their Senecan predecessors, demonstrating his ability to draw upon classical influences while reshaping them to suit his own artistic vision.

Conclusion

Seneca’s tragic form, philosophical depth, and thematic preoccupations with revenge and fate left a profound mark on Shakespeare’s approach to tragedy. Seneca’s use of rhetorical monologues, supernatural elements, and violent retribution provided Shakespeare with a dramatic framework that he both adopted and refined. In Hamlet and Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare mirrors Seneca’s fascination with revenge, yet he complicates it by exploring its psychological and moral ramifications. Similarly, his engagement with Stoic philosophy, evident in characters such as Brutus and Horatio, reflects Seneca’s influence but with greater emotional crisis. The supernatural elements in Macbeth and Hamlet further demonstrate Shakespeare’s indebtedness to Senecan tragedy, yet he moves beyond Seneca by using these devices to deepen character psychology and thematic ambiguity.

However, while Shakespeare clearly draws upon Seneca’s conventions, he does not merely imitate but rather transforms them. Where Seneca’s characters often embody extreme passions or rigid Stoic ideals, Shakespeare’s figures are more psychologically complex and internally conflicted. The stark morality of Seneca’s revenge tragedies (where justice is often equated with brutal retribution) is replaced by Shakespeare’s interrogation of vengeance as a destructive and ethically fraught pursuit. Shakespeare’s tragedies, though structurally and thematically influenced by Seneca, transcend his Roman predecessor by exploring the realities of human nature, presenting characters who struggle with existential doubt, moral dilemmas, and the consequences of their actions.

In conclusion, Shakespeare’s ability to absorb and adapt Seneca’s dramatic techniques while infusing them with greater psychological realism and ethical ambiguity is what makes his tragedies more suited to timelessness. His works are not merely echoes of Seneca’s influence but original masterpieces that engage with the classical tradition while forging new literary and philosophical ground. Shakespeare’s tragedies, unlike Seneca’s, continue to resonate with audiences because they do not provide simple answers but rather ask profound questions about fate, morality, and the human condition.

Works Cited:

- Braunmuller, A. R. (1997). Shakespeare and the Uses of Power. Cambridge University Press.

- Burrow, C. (2007). Shakespeare and Classical Antiquity. Oxford University Press.

- Gibson, R. (2004). The English Tragedy. Oxford University Press.

- Miola, R. S. (1992). Shakespeare and Classical Tragedy: The Influence of Seneca. Oxford University Press.

- Reynolds, L. D. (2018). Seneca and the Idea of Tragedy. Cambridge University Press.

- Shakespeare, W. (2008) The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Wordsworth Editions

- Wilson, E. (2015). Shakespeare and Stoicism. Routledge.

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 280K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments (1)

amazing