"Instruments of Darkness"

Gothic Tropes in Shakespeare's Plays

Background and Context:

Yes, I'm still sifting through those notes I'm finding on essay ideas I had but never wrote from back when I was in university. It was a long time ago but I think I had some pretty good ideas I never explored. Here's one of the finished products.

"Instruments of Darkness"

The Gothic genre, as it is recognised today, emerged in the 18th century with works such as Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764). However, many of its defining features: haunted landscapes, supernatural elements, psychological torment, tyranny, and a preoccupation with death, are already present in the plays of William Shakespeare. While Shakespeare was writing long before the term “Gothic” came into use, his works contain the eerie atmospheres, monstrous figures, and existential dread that would later become staples of Gothic literature. By examining Shakespeare’s use of these tropes, it becomes clear that his tragedies and histories, in particular, prefigure the themes that would dominate Gothic fiction.

This article will explore how Shakespeare’s plays, including Macbeth, Hamlet, King Lear, Richard III, Othello, The Tempest, and Titus Andronicus, employ tropes that are now considered quintessentially Gothic. The discussion will focus on several key themes: the supernatural and the uncanny, madness and psychological horror, tyrannical villains, death and decay, and the sublime and haunted landscapes. These elements do not merely function as dramatic devices but serve to create an atmosphere of terror, dread, and moral uncertainty. In doing so, Shakespeare’s works align with later Gothic concerns about the instability of identity, the power of the irrational, and the collapse of order.

To substantiate these claims, I will not only engage in close textual analysis of Shakespeare’s plays but will also draw upon secondary readings from the Gothic tradition. Dani Cavallaro’s The Gothic Vision (2002) offers a valuable framework for understanding the aesthetic and philosophical dimensions of the Gothic, particularly in relation to the uncanny and the grotesque. David Punter’s A Companion to the Gothic (2000) provides an extensive overview of Gothic literature, tracing its origins and key characteristics, which can be applied retrospectively to Shakespeare’s works. Additionally, Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) will be used to discuss how Shakespeare’s use of vast, storm-ridden landscapes and overwhelming psychological experiences anticipates the Gothic fascination with the sublime: a mixture of awe and terror that defines the genre.

By incorporating these secondary sources, I will demonstrate that Shakespeare’s plays do not simply contain isolated Gothic motifs but engage with a broader Gothic vision that later writers would develop. The interplay between Shakespearean drama and Gothic literature highlights the continuity of certain anxieties: about power, the supernatural, the fragility of reason, and the horrors of the unknown, across centuries of storytelling. And thus, by situating Shakespeare within a Gothic framework, we gain a deeper appreciation of how his work prefigures and shapes the themes that continue to haunt literature and culture to this day.

The Supernatural and the Uncanny

The supernatural is one of the most striking Gothic tropes present in Shakespeare’s plays. His use of ghosts, witches, and otherworldly forces creates an atmosphere of unease and underscores the themes of fate, madness, and moral corruption. These elements align with Gothic concerns about the limits of human understanding and the intrusion of the irrational into the natural world. The uncanny, as defined by Freud, refers to the unsettling experience of something familiar yet disturbingly strange (Freud, 1919). Shakespeare’s supernatural elements contribute to this eerie uncertainty, as characters struggle to interpret ghostly visitations and prophetic warnings.

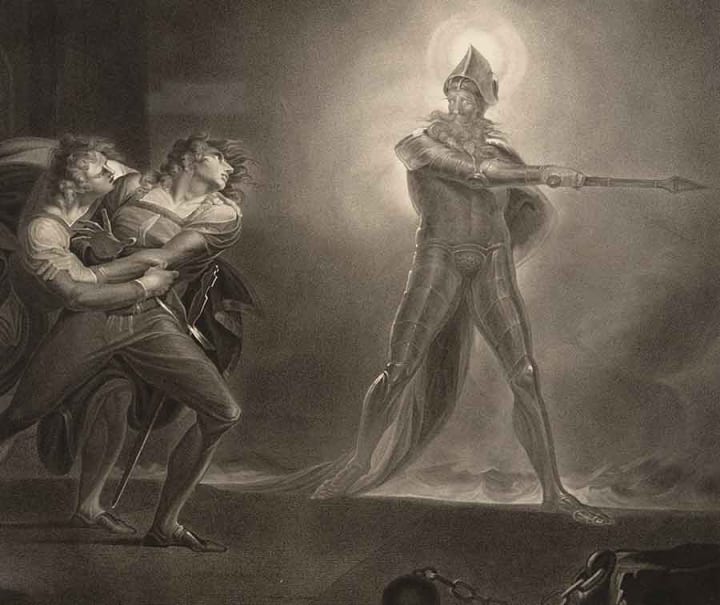

Ghosts play a pivotal role in Hamlet and Macbeth, embodying themes of guilt, fate, and the blurred boundary between life and death. In Hamlet, the appearance of the ghost of King Hamlet sets the entire play in motion, acting as both a harbinger of doom and a catalyst for Hamlet’s descent into existential crisis. The ghost’s ambiguous nature, whether it is truly his father’s spirit or a demonic apparition, reflects a quintessentially Gothic uncertainty. Dani Cavallaro (2002) describes the Gothic ghost as a figure that disrupts time, memory, and reality, a description that aptly fits the ghost in Hamlet, who refuses to be confined to the past and instead haunts the present. Similarly, in Macbeth, Banquo’s ghost is a physical manifestation of Macbeth’s guilt and paranoia, reinforcing the Gothic trope of the past’s inescapable grip on the present. Macbeth’s horror at the sight of Banquo’s spectre illustrates his psychological unraveling, aligning with Burke’s (1757) theory of the sublime, where terror is derived from overwhelming forces beyond human control.

The witches in Macbeth introduce another Gothic staple: prophecy and the supernatural manipulation of fate. The witches’ cryptic messages create a sense of inevitability, drawing on Gothic anxieties about predestination and the loss of agency. Their presence, as well as their ambiguous role as agents of fate or chaos, ties into the Gothic’s preoccupation with the unknown and the manipulation of reality (Punter, 2000). The witches blur the line between the real and the supernatural, much like the ghost of King Hamlet, leaving characters and audiences alike questioning the nature of truth and illusion.

Beyond ghosts and witches, Shakespeare also employs supernatural interventions to construct eerie, otherworldly atmospheres in plays such as The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In The Tempest, Prospero’s magical powers allow him to manipulate nature and people, creating an environment where reality itself is unstable. His island, much like the Gothic castle, is a liminal space where ordinary rules do not apply, and where the supernatural and the natural intertwine. Cavallaro (2002) notes that the Gothic frequently explores isolated, mystical locations that distort perception, a theme that The Tempest embodies through its dreamlike setting and spectral occurrences. Also, A Midsummer Night’s Dream uses fairies and enchantments to unsettle reality, creating a world where identity is fluid, and control is constantly slipping away. These plays engage with Gothic themes by presenting supernatural forces that challenge human reason, reflecting anxieties about the unknown and the fragility of perception.

Shakespeare’s use of the supernatural and the uncanny prefigures key Gothic concerns: the disruption of reality, the intrusion of the past into the present, and the fear of forces beyond human comprehension. By incorporating ghostly visitations, magical manipulation, and eerie settings, his plays establish an atmosphere of dread and uncertainty that would later become fundamental to Gothic literature.

Madness and Psychological Horror

Shakespeare’s portrayal of madness prefigures many of the psychological horrors that would later become central to Gothic literature. His exploration of the mind as a haunted space, where reason gives way to paranoia, delusion, and despair, aligns with the Gothic tradition’s preoccupation with psychological fragmentation and existential terror. In Macbeth, King Lear, Hamlet, and Othello, madness is not only a deeply personal experience but also a force that reflects and amplifies political and social chaos. This connection between personal disintegration and wider disorder is a recurring motif in Gothic fiction, where the individual’s descent into madness often mirrors the collapse of external stability (Punter, 2000).

The motif of psychological deterioration is particularly pronounced in Macbeth, where the protagonist’s guilt and paranoia manifest in disturbing hallucinations. From the moment Macbeth sees the spectral dagger before Duncan’s murder, his grip on reality begins to unravel. His visions of Banquo’s ghost and his compulsive need to seek further prophecies from the witches illustrate his descent into what Dani Cavallaro (2002) describes as the Gothic obsession with fractured subjectivity. Lady Macbeth’s madness, exemplified by her sleepwalking and compulsive hand-washing, similarly demonstrates the Gothic fascination with repressed guilt and the inescapability of past crimes.

In King Lear, madness is both a personal affliction and a symbol of a world turned upside down. Lear’s descent into delirium, triggered by betrayal and the loss of his authority, transforms him into a figure who blurs the boundaries between wisdom and folly. His raving on the heath, where he is exposed to both the storm outside and the tempest within, creates a nightmarish vision of psychological and cosmic disorder. Edmund Burke’s (1757) concept of the sublime (where terror and awe intertwine) is applicable here, as Lear’s madness engenders both horror and profound insight. The play’s bleak vision of a crumbling kingdom further reinforces the link between psychological disintegration and wider societal breakdown, a theme that resonates throughout Gothic literature.

In Hamlet, the theme of madness is particularly ambiguous, oscillating between performance and genuine psychological distress. Hamlet’s feigned madness initially serves as a strategic guise, yet his erratic behaviour and existential musings suggest an internal struggle with despair and paranoia. Sigmund Freud (1919) discusses the uncanny as an experience where the familiar becomes strange and unsettling, a concept that can be applied to Hamlet’s shifting psychological state. His oscillation between rational contemplation and violent outbursts creates an unsettling effect, characteristic of the Gothic’s engagement with unstable identity and unreliable perception.

Othello’s descent into psychological torment, fuelled by jealousy and manipulation, also aligns with Gothic horror’s themes of emotional extremity and psychological instability. Iago’s insidious whisperings function as a corrupting force, much like the demonic figures in later Gothic fiction who drive protagonists toward destruction. Othello’s vision of Desdemona as an unfaithful temptress, culminating in his tragic act of violence, exemplifies the Gothic preoccupation with obsession and the mind’s capacity to construct terrifying false realities. His final moments, in which he realises the horrific consequences of his madness, mirror the profound Gothic theme of tragic self-awareness.

Shakespeare’s depiction of madness as both a personal affliction and a reflection of broader political disorder prefigures the concerns of Gothic literature. His characters experience the mind as a haunted space, where repressed fears and emotions manifest in nightmarish visions and violent actions. This psychological horror, rooted in existential dread and the fragility of identity, establishes Shakespeare as a precursor to the Gothic’s exploration of mental and emotional terror.

Tyranny and the Gothic Villain

The Gothic tradition frequently centres on the figure of the monstrous villain, an individual whose moral corruption, psychological complexity, and often physical deformity render them both terrifying and fascinating. Shakespeare’s exploration of villainy in Richard III, Macbeth, and Othello aligns with this tradition, as his antagonists embody the psychological and political horrors that later Gothic literature would intensify. These characters, driven by ambition, manipulation, and unchecked power, foreshadow the archetypal Gothic villain who exerts a nightmarish influence over both individuals and societies (Punter, 2000).

Richard III is perhaps Shakespeare’s most overtly Gothic villain, his physical deformity serving as both a symbol and a justification for his ruthless ambition. From the outset, Richard frames himself as an outsider, shaped by his physical difference into a figure of relentless cunning and cruelty: ‘I am determined to prove a villain’ (Richard III, I.i.30). His elaborate deception, merciless manipulation, and willingness to murder even his own kin position him as a precursor to the Gothic anti-hero, whose charisma and intelligence make him a compelling yet repellent figure. Dani Cavallaro (2002) notes that Gothic villains often exert a ‘hypnotic allure,’ drawing others into their schemes even as they repulse them—a quality evident in Richard’s ability to seduce Lady Anne despite having murdered her husband and father-in-law.

Macbeth’s transformation from a noble warrior to a bloodthirsty tyrant exemplifies another facet of Gothic villainy: the descent into monstrous ambition. Unlike Richard III, Macbeth begins as an honourable man, but his susceptibility to supernatural influence and his unchecked desire for power lead him to commit increasingly horrifying acts. The Gothic’s preoccupation with fate and prophecy is evident in the witches’ role in igniting Macbeth’s ambition, and his eventual paranoia and descent into madness mirror the psychological torment typical of the Gothic protagonist. As Burke (1757) argues in his theory of the sublime, terror arises from the unknown and the uncontrollable; both of which pervade Macbeth’s rule as he becomes haunted by Banquo’s ghost and obsessed with maintaining his fragile grip on power.

In Othello, Iago embodies the insidious and manipulative villainy characteristic of the Gothic. Unlike Richard III or Macbeth, Iago’s evil is not driven by ambition for power but by a seemingly motiveless malignity, making him even more disturbing. He operates as a Gothic tempter figure, planting doubts and fears in Othello’s mind and orchestrating his psychological downfall. Freud’s (1919) concept of the uncanny, where the familiar becomes strange and unsettling, is evident in Iago’s ability to warp reality, turning Othello’s love into suspicion and his noble identity into monstrous rage. The way Iago manipulates language and perception, shifting from false friendship to venomous deceit, reflects the Gothic’s obsession with unstable identity and hidden horrors.

Across these plays, Shakespeare presents villains who embody the terror and fascination of Gothic monstrosity. Whether through physical deformity, unchecked ambition, or psychological manipulation, Richard III, Macbeth, and Iago prefigure the Gothic tradition’s most enduring figures of evil; whose whose presence haunts both the characters within their narratives and the audiences who witness their chilling descent.

Death, Decay and the Macabre

One of the defining features of Gothic literature is its preoccupation with death, decay, and the macabre. Shakespeare’s plays abound with morbid imagery, from Hamlet’s meditation on the inevitability of death to the grotesque excesses of Titus Andronicus. His tragedies, in particular, explore the unsettling presence of corpses, blood, and murder, foreshadowing the Gothic tradition’s fascination with the unsettling aspects of mortality. As Cavallaro (2002) notes, the Gothic is deeply invested in ‘the aesthetics of decay,’ which manifest in Shakespeare’s relentless depiction of physical and psychological disintegration.

In Hamlet, the titular character’s obsession with death is exemplified in the graveyard scene, where he contemplates the skull of Yorick, the king’s former jester: ‘Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio’ (Hamlet, V.i.184). This moment, rich with Gothic overtones, forces Hamlet to confront the transience of life and the inevitable decay of the human body. The motif of rot and corruption pervades the play, with Hamlet describing Denmark as ‘an unweeded garden’ (Hamlet, I.ii.135) and referring to the spreading moral and political decay that mirrors physical decomposition. Edmund Burke’s (1757) concept of the sublime, which links beauty to terror, is evident in Hamlet’s simultaneous horror and fascination with death, a paradox central to the Gothic aesthetic.

Titus Andronicus, often regarded as Shakespeare’s most gruesome work, revels in the visceral horrors of dismemberment, cannibalism, and brutal revenge. Lavinia’s mutilation: her hands cut off and her tongue removed, transforms her into a living corpse, a haunting presence that embodies the play’s relentless descent into carnage. The climactic banquet scene, where Titus serves Tamora a pie made from the flesh of her own sons, exemplifies the grotesque excesses that later Gothic fiction would embrace. Punter (2000) highlights how Gothic horror often dwells on the body as a site of both suffering and spectacle, a theme unmistakable in Titus Andronicus, where bodies are not just destroyed but displayed as emblems of vengeance and corruption.

Beyond these explicit depictions of death, Shakespeare’s tragedies frequently feature the eerie presence of corpses and the return of the dead. Macbeth is haunted by the image of Banquo’s ghost, a spectral reminder of his crime that fuels his paranoia. Similarly, Julius Caesar features the ghost of the murdered dictator warning Brutus of his impending doom, reinforcing the Gothic trope of the restless dead seeking retribution. Freud’s (1919) theory of the uncanny is particularly relevant here, as these ghostly apparitions blur the line between the living and the dead, creating a profound sense of unease.

Through its exploration of mortality, horror, and bodily decay, Shakespeare’s work anticipates the Gothic’s obsession with the grotesque and the spectral. Whether through Hamlet’s reflections on death, the horrific spectacle of Titus Andronicus, or the omnipresent ghosts in his tragedies, Shakespeare’s engagement with the macabre continues to resonate within the Gothic tradition.

The Sublime and Haunted Landscapes

A fundamental aspect of Gothic literature is its emphasis on sublime and haunted landscapes. settings that evoke awe, terror, and a sense of the supernatural. Shakespeare frequently employs eerie and tumultuous environments to reflect his characters’ psychological turmoil and the broader chaos of the world they inhabit. His plays, particularly Macbeth, King Lear, Hamlet, and The Tempest, anticipate the Gothic tradition’s use of stormy settings, liminal spaces, and nature’s raw, uncontrollable power. As Burke (1757) articulates in his discussion of the sublime, terror and beauty are deeply interwoven, and this interplay is crucial to Shakespeare’s construction of landscapes that unsettle both characters and audiences alike.

The role of stormy and eerie settings is particularly pronounced in King Lear and Macbeth. Lear’s exposure to the raging tempest on the heath in Act III is more than just a physical ordeal: it mirrors his descent into madness and his confrontation with the fragility of human existence. The storm itself, described as one that ‘tears his white hair’ (King Lear, III.ii.7), becomes an almost supernatural force, reflecting the cosmic disorder that Lear’s folly has unleashed. Similarly, in Macbeth, the ‘thunder and lightning’ (Macbeth, I.i.1) that accompany the witches’ first appearance establish an atmosphere of ominous foreboding, reinforcing the play’s themes of fate, chaos, and unnatural disruption.

Shakespeare’s use of Gothic architecture: castles, dungeons, and liminal spaces, is crucial in heightening the eerie tension within his plays. Elsinore Castle in Hamlet is a quintessentially Gothic space: a fortress riddled with secrets, haunted by the ghost of the former king, and permeated with a sense of entrapment. The castle’s oppressive atmosphere reflects Hamlet’s existential crisis and the corruption festering within the state of Denmark. Also, Macbeth’s Scotland is a realm shrouded in darkness, where castles such as Inverness become sites of treachery, murder, and psychological horror. Dani Cavallaro (2002) notes that Gothic settings often function as ‘prisons of the mind,’ and Macbeth’s castle exemplifies this concept as it transforms from a place of hospitality to a blood-soaked fortress of paranoia and tyranny.

Nature itself, in its terrifying and uncontrollable form, also plays a key role in Shakespeare’s proto-Gothic landscapes. The Tempest exemplifies the sublime power of nature, with Prospero’s storm serving as both a physical and metaphorical manifestation of vengeance and disruption. The island, isolated and mysterious, embodies the Gothic trope of the unknown wilderness where magic, the supernatural, and psychological manipulation reign supreme. In King Lear, the natural world becomes an almost sentient force of destruction, mirroring the collapse of political and familial order. As Punter (2000) asserts, the Gothic landscape is often used to ‘externalise the fears and desires of the human psyche,’ and in Shakespeare’s works, storms, castles, and ungovernable nature function as mirrors to the inner turmoil of his characters.

In these sublime and haunted landscapes, Shakespeare establishes an aesthetic and thematic foundation that would later define Gothic literature. His use of tumultuous weather, dark and foreboding architecture, and nature’s uncontrollable power creates an enduring sense of unease, anticipation, and psychological complexity that resonates within the Gothic tradition.

Conclusion

Shakespeare’s exploration of darkness, psychological tension, and supernatural elements in plays such as Macbeth, Hamlet, and King Lear laid the groundwork for many themes later explored in Gothic literature. His use of moral ambiguity, the supernatural, and troubled protagonists with inner conflict set a precedent for the brooding, psychological depth that defines the Gothic genre. Shakespeare’s portrayal of madness, power struggles, and the interplay between fate and free will influenced later writers who embraced these themes in more elaborate settings, drawing on the eerie atmosphere and complex characters he developed.

Writers like Horace Walpole, Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Brontë sisters all drew inspiration from Shakespeare’s Gothic elements. Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), often considered the first Gothic novel, incorporated supernatural events and psychological terror similar to the tensions found in Shakespeare’s tragedies. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) echoes the theme of forbidden knowledge and the tragic consequences of unchecked ambition, much like Macbeth's destructive ascent to power. Edgar Allan Poe, with his psychological horror and gothic aesthetics, reflects Shakespeare’s exploration of madness and inner turmoil. The Brontës, especially in works like Wuthering Heights, demonstrate the influence of Shakespeare’s complex characters and dark, brooding settings.

These Shakespearean Gothic tropes still resonate in modern horror and Gothic fiction, where themes of madness, the supernatural, and moral ambiguity continue to captivate audiences, proving the enduring power of his influence in shaping the genre.

Works Cited:

- Burke, E. (1757) A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. London: R. and J. Dodsley.

- Cavallaro, D. (2002) The Gothic Vision: Three Centuries of Horror, Terror and Fear. London: Continuum.

- Freud, S. (1919) ‘The Uncanny’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919). London: Hogarth Press.

- Punter, D. (2000) A Companion to the Gothic. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Shakespeare, W. (2008) The Complete Plays of William Shakespeare. UK: Wordsworth Editions.

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 280K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments (2)

I am a fan of your writing

Very good work 👏🏻