Book Review: "Reliable Essays" by Clive James (Part 1)

5/5 - Clive James proves he knows his stuff when it comes to George Orwell and Evelyn Waugh, a headstrong critic of 20th century English Literature...

Disclaimer:

This is Part 1 of a series of reviews of "Reliable Essays" by Clive James. Here, I feature the author's note, the introduction, George Orwell and Evelyn Waugh. In the next part of the series, you will find: Nabokov, Travel Writing of Rome and Norman Mailer on Marilyn Monroe.

Book Review: "Reliable Essays" by Clive James

(Part 1)

I hope you're ready for another nonfiction anthology deep-dive just like we did back in the 'Pulphead' era, because I am. For those of you who are new to this: every now and again I like to do a deep-dive into a nonfiction anthology of essays, exploring the writing style and topics the author has chosen, picking apart ideas and theories, statements and stories. So, be prepared for something pretty lengthy and as always, there's no TL;DR of course. Strap in and prepare yourself for another deep-dive as we start to hit the waters of this excellent anthology by Clive James.

Author's Note

"Even the aphorist, who tries to do the winnowing in advance, is winnowed in his turn: writing a hundred words to stand for a thousand, he would feel flayed to discover that only ten of them got through."

- 'Author's Note' of Reliable Essays by Clive James

In his author's note, James explains that a compilation of a life of writing does not have to consist of every bit of writing ever done by the person in question. We do not require every instance to prove someone was a keen and apt writer, but instead the best examples of the passion of writing that come through in their hard work. He works on this idea, chewing it out in his regular fashion by surrounding it with metaphor and decision. Of course it is then he introduces another man to the realm: Julian Barnes - who writes the introduction. Of course, this means I am very excited to read this anthology.

Introduction

Barnes reflects on his friendship with Clive James, stating that there is something very special about how they have seen each other over the decades. He makes observations of academia and how it's meaning and implications have changed over time by starting with:

"...a character in a novel some years ago described academics as merely 'reviewers delivering their copy a hundred years late.'"

He states that this is no longer the case before diving into the way in which Clive James changed the whole scene with both his well-read brain and his differing Australian nature. He separates Clive James the TV guy from Clive James the literature guy and welcomes him back in what is perhaps one of the most fashionable introductory sections to any nonfiction book I have ever read.

No, I'm not going through every single essay, don't worry. I will however, be covering the ones I thought were the most important and possibly the best written in the anthology.

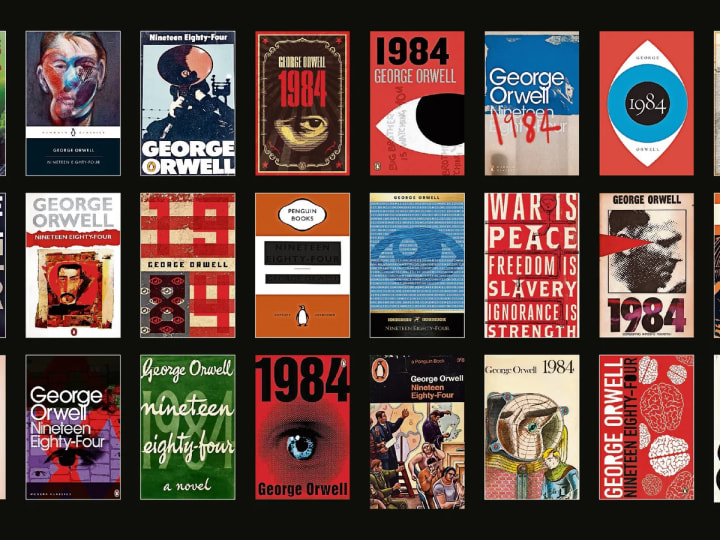

The All of Orwell

Clive James certainly has a love for everything Orwell, and that's not to say he loves things that are considered Orwellian. He hammers home that distinction and teaches us that most of what we have considered to be associated with the term 'Orwellian' is not actually that at all. He clarifies that the very nature of being 'Orwellian' sort of locks George Orwell's writings and beliefs into a box that usually only contain his two famous novels.

He talks about how he first got Orwell's journalistic writings and honestly, I think we all have to appreciate the way in which Clive James writes long metaphors about branches but even more importantly, there are the shorter ones like this:

"The All of Orwell arrives in a cardboard box the size of a piece of check-in luggage: a man in a suitcase."

Seemingly implying that Orwell is quite literally his own writings, which would be true for those of us who have read essays such as Shooting the Elephant in his "Selected Works". It was one of the best nonfiction anthologies I had read that year. Clive James however moves on to looking at the fact that though Orwell had influences, he was not to be lulled into submission by any of them. Having influences but also being able to forge your own thought is basically an archaic skill in the age of social media.

Again, if I have said it before I think I have to say it once more, Clive James has the best metaphors and similes. When he starts to cover the life of Orwell, he goes in deep to his prep school years commenting on the way in which Orwell wrote one of his final essays, apparently in which he:

"...painted his years at prep school...as a set of panels by Hieronymus Bosch."

I think we can all imagine how his prep school years went down just by reading this figurative language. I would recommend the essay as well though because you really want to flesh the idea out. If you however, have not looked at the works of Hieronymus Bosch, then do that immediately and first out of all of the previous instruction.

He moves through Orwell's time at Eton and into his philosophies and politics. James ends up looking through the lens of Orwell's journalistic works to examine how his time in different countries such as Spain and Burma shaped how he saw the state of the world. He comes to the conclusion that Orwell perhaps believed that 'the enemy was totalitarianism itself' and one more important thing, told again to us through the use of a grand metaphor:

"...capitalism was a disease, socialism was the cure and Communism would kill the patient..."

I don't know about you, but I love that metaphor a lot. I have never read Orwell's politics so succintly summarised into something that is so grand and yet, understandable. But Clive James does not rest his metaphorical nature there when it comes to articulating George Orwell's politics. He also examines the stance Orwell took on fascism - admitting that when it came to his political understandings of his own time and place, he was a 'late developer'. He states in the essay:

"Fascism, he proclaimed, was just bourgeois democracy without the lip service to liberal values, the iron fist without the velvet glove."

Apart from talking about how Orwell understood the British political system as being based on a series of class plights and classist natures, Clive James also focuses on Orwell's perspective on other writers - including those such as Thomas Mann. This is to also address the changing politics of Orwell and how the writer reconciles that within himself:

"[Thomas Mann] never pretends to be other than he is, a middle-class Liberal, a believer in the freedom of the intellect, in human brotherhood; and above all, in the existence of objective truth."

Clive James' writing on Orwell's changing belief systems is something to behold because even though James praises the writer for his exploits, he also admits that perhaps he was not coming clean about having 'rearranged the playing field', also implying that Orwell's views were not really polished up until his final few years when he wrote his most incredible novels.

Clive James examines British society under the lens of how Orwell would have seen it and afterwards. He looks at the post-war state of Britain, which would be in Orwell's final years. He writes it again, in a brilliantly simplistic style, articulating what makes British society and politics special and individualistic. He writes:

"British society, ever since World War II, has continuously been one of the more interesting experiments in the attempt to reconcile social justice with personal freedom."

From all the way down the line to Stalinism, it is clear that James understands Orwell's deepest and most important critiques going on which happen not just to be about Russia but about how the ultra-left-wing liberal intellectuals have hijacked the essences from Communism, using it within their own intellectual spaces for the leverage of influence. Something akin to what we can see happening today. And as Clive James articulates, it is all relative to language and thought.

"The main drive of all of Orwell's writing since Spain had been to point out that the Soviet Union...had systemically perverted language in order to cover up the wholesale destruction of human values, and that the Western left-wing intellectuals had gone along with this by perverting their own language in its turn."

This is perhaps my favourite line from the entire essay because it is relative not only to the time it is applicable to (Orwell's decade) but also down the line to McCarthyism, down the line again to the thought police we seem to have in place today as well and of course, elsewhere all over the world. One thing that Orwell was frightened was happening was this overhaul of language by the political protection of certain classes of people. Konstantin Kisin talks about a similar thing in his book An Immigrant's Love Letter to the West in which he describes the problem with the very word 'diversity' and how it has been distorted.

"Unless he is alert to the trickery of his own magic, will project an air of Delphic infallibility that can do a lot of damage before the inevitable collapse into abracadabra."

The way the essay ends is in classic Clive James style, filled with metaphorical language and circling a certain theme that is only relative to those who have read the entire essay for what it is: George Orwell was a great writer, a great political thinker too, but he wasn't afraid to shift his position around the board over the course of his life - and sometimes he was wrong.

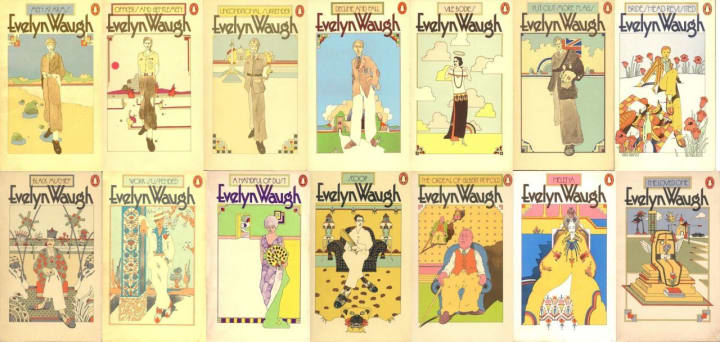

Evelyn Waugh's Last Stand

I don't know whether I've explained this before but Evelyn Waugh is perhaps one of the most perfect examples of separating the art from the artist. We can't deny that Brideshead Revisited is one of the best novels of the 20th century but we can also accept it was written by a man who was probably not in his right mind most of the time. Clive James starts this same analysis off with the fact that all Waugh novel fans love: his hatred of the telephone. James sets up Waugh's hatred of modernity as part and parcel of expanding his personality into the depths of his letters. It is clear we are dealing with an ageing Evelyn Waugh who is less in his right mind than he was before:

"Here is yet one more reason to thank Evelyn Waugh for his hatred of the modern world. If he had not loathed the telephone, he might have talked all this way."

Referring to Waugh's quite distinct and (in my opinion) unlistenable voice, I am only guessing that Clive James feels the same way I do. But he moves on to, as I have explained, expand upon Waugh's discontent for modernisation which rakes in Waugh's ardent racism with it. The funny thing here is that England was mostly Protestant by Waugh's time period and yet, as a convert to Catholicism, Waugh not only hated Protestants but he also hated people born Catholic in a style that I can only describe as that of Jordan Peterson when he gets lost down the theological rabbit hole. He hates their loose morals, as he likes to call it - their ability to commit sin even though they are Catholic.

"Waugh was equally nasty about any other social, racial or ethnic group except what he considered to be pure-bread, strait-laced, upper-class Catholic English"

Rattling off some derogatory names for various races and religious groups, it is hard to believe that Clive James has actually lifted these words straight from the letters of Evelyn Waugh himself. But of course he has. James describes as well, that one of the main factors that contributed to the 'downfall' of Evelyn Waugh was his proclivity for anti-semitism. Even after World War 2, James explains that Waugh was still an anti-semite; less overt, but more casual. I'm not sure I would know which is worse. Waugh definitely had anti-semitism as a core part of his personality. I'm not surprised but this is something we must move away from his art if we really want to understand and enjoy things. A lot of artists have a dark side, none of them are as proud of it as Evelyn Waugh though:

"Waugh was perfectly capable of seeing that to go on indulging himself in anti-Semitism after World War Two was tantamount to endorsing a ruinously irrational historical force. But Waugh, with a sort of cantankerous heroism, refused to let the modern era define him."

Simultaneously though, he is also this quotation:

"Behaving as if recent history wasn't actually happening was one of Waugh's abiding characteristics."

One of the words Clive James uses to describe Evelyn Waugh's beliefs and values, especially when it comes to his ideals is "fantasy". Even when it comes to other people, the ideal Evelyn Waugh puts forward is a "fantasy". As if not only it could never exist, it was also perhaps that it best didn't go on for very long. Of course, fantasies lose their novelty after a while and then we all have to face reality. The modern reality though seems too extreme and changing for Waugh, who is still stuck in a conservative 19th-century mind-set.

I wonder though if Waugh's fantasy comes more to fruition after his divorce as a coping mechanism. Clive James explains that Evelyn Waugh was "born with his world view intact" but I can definitely see parts of him that were exemplified by certain things that happened in the world and in his life. James explains:

"The misery he was plunged to when his first wife left him still comes through. In the pit of despair, he finished writing 'Vile Bodies' which remains one of the funniest books in the world."

Satirical as it is, I would not call Vile Bodies the funniest book in the world and also wonder whether Clive James has indulged himself in A Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. But it's clear Waugh's satire is definitely sharpened in 'Vile Bodies' for sure.

As Clive James treads carefully over the work and life of Evelyn Waugh, he gets to the million-dollar question about snobbery and offers us an answer:

"Asking whether Evelyn Waugh was a snob is like asking whether Genghis Khan was an authoritarian."

There are several comparisons between Waugh and his character Guy Crouchback from Sword of Honour and I think I am right by saying there is perhaps a little Sebastian Flyte in the guy too, though it's never explicitly mentioned in the essay. There's a longing for simplicity. That simplicity is Aloysius - the bear. Evelyn Waugh famously misunderstood the changing world after the wars and definitely had this requirement that we all have when change approaches - to go back. He wanted to retreat. His proud openness concerning his classism and racism therefore, is (as I have already stated), this coping mechanism for the discomfort of the modern age. He wants to be proud of retreating because it makes him seem like a contrarian. It is clear though that he is miserable with his reputation in private. He was definitely a man divided.

This comes through again when Clive James explains (to my shock as well) that Evelyn Waugh declined a CBE. This made so little sense to me until I read the entire passage. He had a keen dislike for one of his dinner guests (Sir Laurence Olivier) and was himself, expecting something more than a CBE, as James describes that Waugh was 'more royalist than the King'. But, as Waugh did not yet do anything to quite deserve the stance of a knighthood, he would have had to work his way up to it. Something that I think all Evelyn Waugh novel fans know by now, he does not find appealing to do. Clive James explains about Waugh turning down the CBE:

"In this he differed from the true climber, whose whole ability is to never put a foot wrong. Waugh put a foot wrong every day of the week. Quite often he put the foot in his mouth."

Waugh's 'necessary fantasy' of Brideshead Revisited was therefore something we cannot be surprised by. His honest belief of people having to 'know their place before they could see their duty' was perhaps one of his most infamous ideals presented. Again, this is set up against Waugh's time in the army. It was miserable and resulted in him being left behind. This follows on from my point about Waugh being unable to connect with others, especially given that he was so secluded for most of his life to certain groups of people.

Another aspect of this want to be part of certain groups through coping mechanism snobbery we see of Evelyn Waugh is through the dichotomy presented by snobbery and sadness. It is clear that Waugh was more than simply miserable. Clive James explains his situation:

"He was paid out for his rancour by his own unhappiness."

He uses the post-script quite well to admit that the first time he read Evelyn Waugh, he thought him a satirist of those conservative aristocratic English values commonly associated with country manors and snobby rich people - only to find he was one himself. The universality of this belief is astounding and I think we all share the same story when discovering this strange and bewildering author.

You almost feel bad for enjoying his works.

Conclusion

I hope you come back for the next part. This is very exciting and I have a lot I want to talk about.

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 280K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (1)

I feel bad because I do not enjoy his works that much. I have mixed feelings about the essays, although I have the same interests. And I saw a video where he reenacted scenes from a Graham Greene book (very funny). Maybe I should give him another chance? I need to do something after our last election... ;)