These Countries Have Declined Trump’s Invitation to Join Gaza ‘Board of Peace’

Western hesitation and geopolitical fault lines emerge as major powers reject a U.S.-led peace initiative

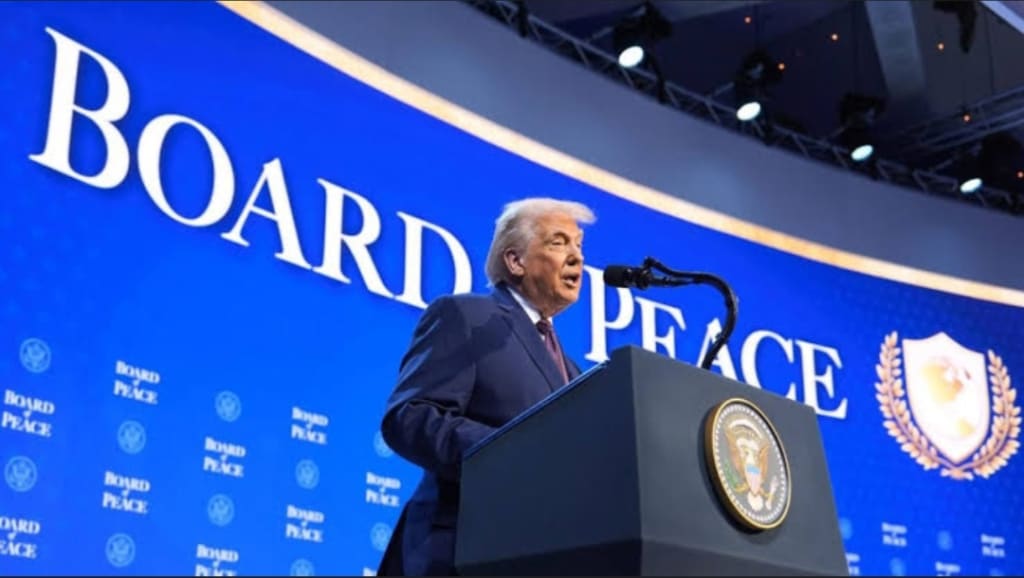

In late January 2026, U.S. President Donald Trump’s launch of the “Board of Peace” — a new multinational body intended to oversee Gaza’s post-war reconstruction and broader global conflict mediation — was met with a striking global diplomatic response. While several nations, especially from the Middle East and Asia, accepted Trump’s invitation, a notable group of countries explicitly declined or refused to join the initiative. Their decisions reflect deep concerns about the board’s structure, its relationship to the United Nations (UN), and broader geopolitical dynamics shaping the post-Gaza peace landscape.

At the heart of this diplomatic pushback is skepticism from Western and European nations over the board’s mandate, its proximity to U.S. interests, and whether it undermines existing international institutions. This article explains which countries said “no,” why they declined, and what these refusals mean for the future of Gaza’s peace process.

---

What Is the “Board of Peace”?

Before delving into the countries that turned down the invitation, a brief overview is essential. The Board of Peace was formally announced by President Trump at the World Economic Forum in Davos, as part of an ambitious plan to end the Israel-Hamas war and manage Gaza’s transition from conflict to stability. According to U.S. officials, the board is designed to coordinate reconstruction, monitor ceasefire adherence, and potentially evolve into a broader conflict-resolution body. This initiative also hinges on a controversial $1 billion permanent membership contribution from participating countries, and — as critics note — gives Trump indefinite chairmanship, raising questions about geopolitical balance and accountability.

---

Key Nations That Declined the Invitation

France

One of France’s most notable decisions was to refuse the invitation outright. French President Emmanuel Macron and his government argued that the Board’s charter “goes beyond the framework of Gaza” and risks undermining the authority of the United Nations and international law. France emphasized that peacebuilding must align with UN principles and include Palestinian leadership, rather than being driven by a new body led by a single nation’s president.

---

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom – a traditional U.S. ally – also declined to participate. British leadership underscored its support for the existing UN-led, rules-based international system and expressed concern that the Board’s mandate could conflict with this framework. UK officials have stressed that any peace mechanism must be consistent with established multilateral institutions rather than creating parallel structures.

---

Germany

Germany, too, balked at joining the Board in its current iteration. Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s spokesperson said Berlin could not accept participation on “constitutional grounds.” While Germany reaffirmed its commitment to global peace and stability, it made clear that the Board’s design raised legal and institutional issues, particularly related to its potential overlap with UN authority.

---

Spain

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez echoed similar reservations, stressing that the Board operates outside established international frameworks and lacks direct representation from the Palestinian Authority — a central stakeholder in Gaza’s future. Spain’s rejection was framed both as a principled defense of multilateralism and a call for peace processes to be led by Palestinians themselves.

---

Nordic Countries: Norway and Sweden

Norway and Sweden also declined, citing broader concerns about the initiative’s ambiguity and potential conflict with UN norms. Official statements from Oslo indicated a desire for wider consultation and dialogue with other partners, rather than a unilateral commitment to a U.S.-led board that could overshadow existing diplomacy. Sweden made similar points, noting that its foreign policy priorities align more closely with multilateral peace mechanisms.

---

New Zealand

New Zealand’s government confirmed that it would not join the Board “in its current form.” Foreign Minister Winston Peters explained that multiple regional states were already engaging in Gaza’s recovery, and that New Zealand’s involvement would not add “significant value.” Importantly, Wellington emphasized that any peace initiative should be complementary to the UN Charter, and urged greater clarity on the board’s long-term mandate.

---

Italy and Canada: Special Cases

While not outright refusals in the same vein, Italy and Canada also deserve mention. Italy has taken a more cautious position, suggesting that it would consider participation only if the Board’s scope evolved. Canada initially indicated an openness but faced a diplomatic rift when President Trump revoked its invitation following criticisms from Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney. This move highlighted how political tensions can quickly reshape international cooperation.

---

Why So Many Major Powers Said No

Concerns Over UN Authority

A shared theme among the declining nations is the perceived threat the Board poses to UN mechanisms, especially the Security Council and peacebuilding agencies. Many European countries prefer to channel resources through existing multilateral systems they view as more inclusive and legitimate.

---

Mandate and Structure Issues

The Board’s broad, multi-purpose reconstruction and peace mandate, coupled with its leadership structure — dominated by the United States — has raised concerns about transparency, accountability, and equitable participation. Critics argue that a U.S.-centric board could undermine long-established diplomatic channels and sideline key voices in the peace process.

---

Geopolitical Signaling

Refusals were not merely administrative; they also sent political signals. By declining, many Western states reaffirmed their commitment to collective diplomacy and multilateralism — implicitly pushing back against unilateral or bilateral frameworks that could realign global influence.

---

What This Means for Gaza and Global Diplomacy

The rejection by major Western powers complicates Trump’s vision for the Board of Peace. While dozens of countries — particularly from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia — have accepted invitations, the absence of key European democracies and traditional allies raises doubts about the board’s global legitimacy and long-term effectiveness.

For Gaza, this high-profile diplomatic divergence underscores the challenge of building consensus around reconstruction and governance. Critics argue that without a genuinely inclusive approach and adherence to UN principles, peace efforts risk fragmentation and future setbacks.

As international leaders watch closely, the Board of Peace’s next moves — including whether it will reform its structure or deepen ties with the UN — could influence not only Gaza’s recovery but broader norms governing global conflict resolution in the 21st century.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.