Lost After Gained

Exploring the Psychology Behind the Diminishing Allure of Our Greatest Wants

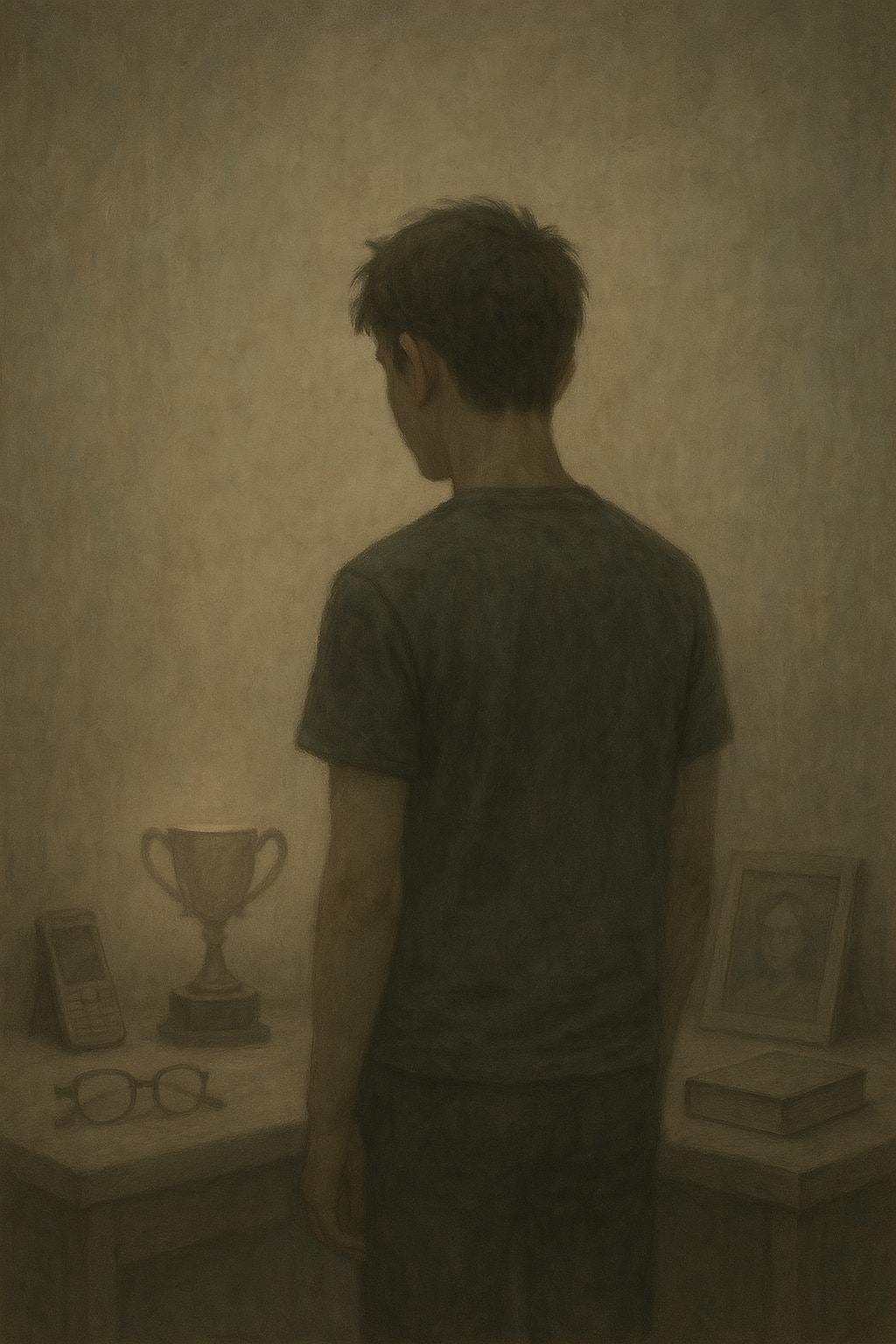

You dream about it. You obsess over it. You imagine the moment you'll finally get it — that job, that relationship, that car, that home, that recognition. And then one day… it's yours. At first, there's a rush. Satisfaction. Triumph. But as days pass, the shine wears off. The object of your desire fades into the background of daily life. What once thrilled you now barely moves the needle. Why?

This phenomenon — where our interest and appreciation for something drops dramatically once we've attained it — is not a personal failing. It’s a predictable pattern deeply rooted in psychology, neuroscience, and culture. And it tells us a lot about what we really want — and what we’re often missing.

1. The Hedonic Treadmill: Always Running, Never Arriving

At the core of this pattern is a psychological concept called hedonic adaptation. It's the human tendency to return to a stable level of happiness despite major positive or negative events. In other words, we get used to things — fast.

That dream house? You’ll stop noticing the high ceilings in a few months.

That promotion? It becomes just another line on your LinkedIn.

That luxury watch? The dopamine hit fades with every glance.

We're biologically wired to adapt, because historically, adaptation helped us survive. But in modern life, it creates a treadmill effect: no matter how fast we run toward desires, we stay in place emotionally.

2. Anticipation is a Drug

There's something uniquely intoxicating about wanting. When we crave something, our brain releases dopamine — the pleasure chemical. But here’s the twist: dopamine is more about anticipation than it is about reward.

When you imagine your future success, you're building stories. You're fantasizing about a better version of yourself. The pursuit becomes a source of identity. But once the goal is achieved, the story ends — and without a new narrative, your brain loses interest.

3. Desire is Identity-Building

Many people don't just want things — they become their desire. They define themselves by what they’re working toward. “I'm going to be an author.” “I'm going to start my own company.” “I'm going to move to Paris.”

Once they get there, they often feel a surprising hollowness. That’s because the chase was serving as a scaffolding for self-worth and meaning. When that scaffolding is removed, we’re left with the uncomfortable question: Now what?

4. The Scarcity Principle and Psychological Value

We assign greater value to what is scarce or unattainable. The moment something becomes ours, it loses that elusive quality.

This is especially true in relationships. People often idolize a partner they can’t have — but once that person returns their affection, the fantasy breaks. The real person can never compete with the idealized version we’ve created in our minds.

In economics, this is known as diminishing marginal utility. The first bite of cake is bliss. The fifth? Meh. The same logic applies emotionally.

5. Capitalism, Culture, and the Moving Goalpost

Modern culture fuels dissatisfaction. We're constantly bombarded with images of what we should want — thinner bodies, bigger houses, faster cars, flashier vacations. Even after we acquire something, society quickly nudges us toward the next desire.

Social media exacerbates this. We compare not just upward, but relentlessly. Your new phone might impress you… until your friend shows off the next-gen model.

This results in a cultural trap: contentment becomes rebellion, and insatiability becomes the norm.

6. Gratitude Deficiency and the Art of Presence

One of the key reasons we stop appreciating what we have is because we never trained ourselves to.

Gratitude isn't just a buzzword. It’s a mental discipline that retrains your mind to notice. To pause. To resist the pull of constant forward motion. Studies show that regularly practicing gratitude literally rewires the brain — increasing dopamine, reducing cortisol, and enhancing overall life satisfaction.

When we don’t do this, we fall into a dangerous feedback loop: acquire → normalize → desire something else → repeat.

7. The Cure is in the Question, Not the Answer

Instead of constantly asking “What’s next?”, maybe we need to ask:

Why did I want this so badly?

What did I think it would give me?

Was it the object I wanted, or the feeling behind it?

Most desires are surface-level expressions of deeper emotional needs: security, love, recognition, autonomy. When we skip that inner interrogation, we end up chasing shadows instead of addressing root longings.

8. How to Break the Pattern

If you want to stop undervaluing the things you once cherished, try:

Journaling your milestones. Write about what you wanted and how it felt to get it. Revisit these entries.

Savoring rituals. Build small habits around appreciating what you have — morning coffee in silence, walking through your apartment as if seeing it for the first time.

Desire fasting. Occasionally go without buying or pursuing anything new. Let your mind recalibrate.

Purpose over possession. Attach your energy to meaningful projects or causes rather than items or status.

Conclusion: The Quiet Tragedy of Having It All

The real danger isn’t in never getting what you want. It’s in getting it — and feeling nothing.

But that doesn’t have to be a tragedy. It can be a turning point. A nudge to reorient your compass. To stop chasing, and start seeing. To value the now not because it’s rare, but because it’s real.

Your most prized possessions, relationships, or achievements don’t need to dazzle to be worth something. Sometimes, their true worth only becomes visible when we stop looking for the next thing — and start remembering why we wanted them in the first place.

About the Creator

Ahmet Kıvanç Demirkıran

As a technology and innovation enthusiast, I aim to bring fresh perspectives to my readers, drawing from my experience.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.