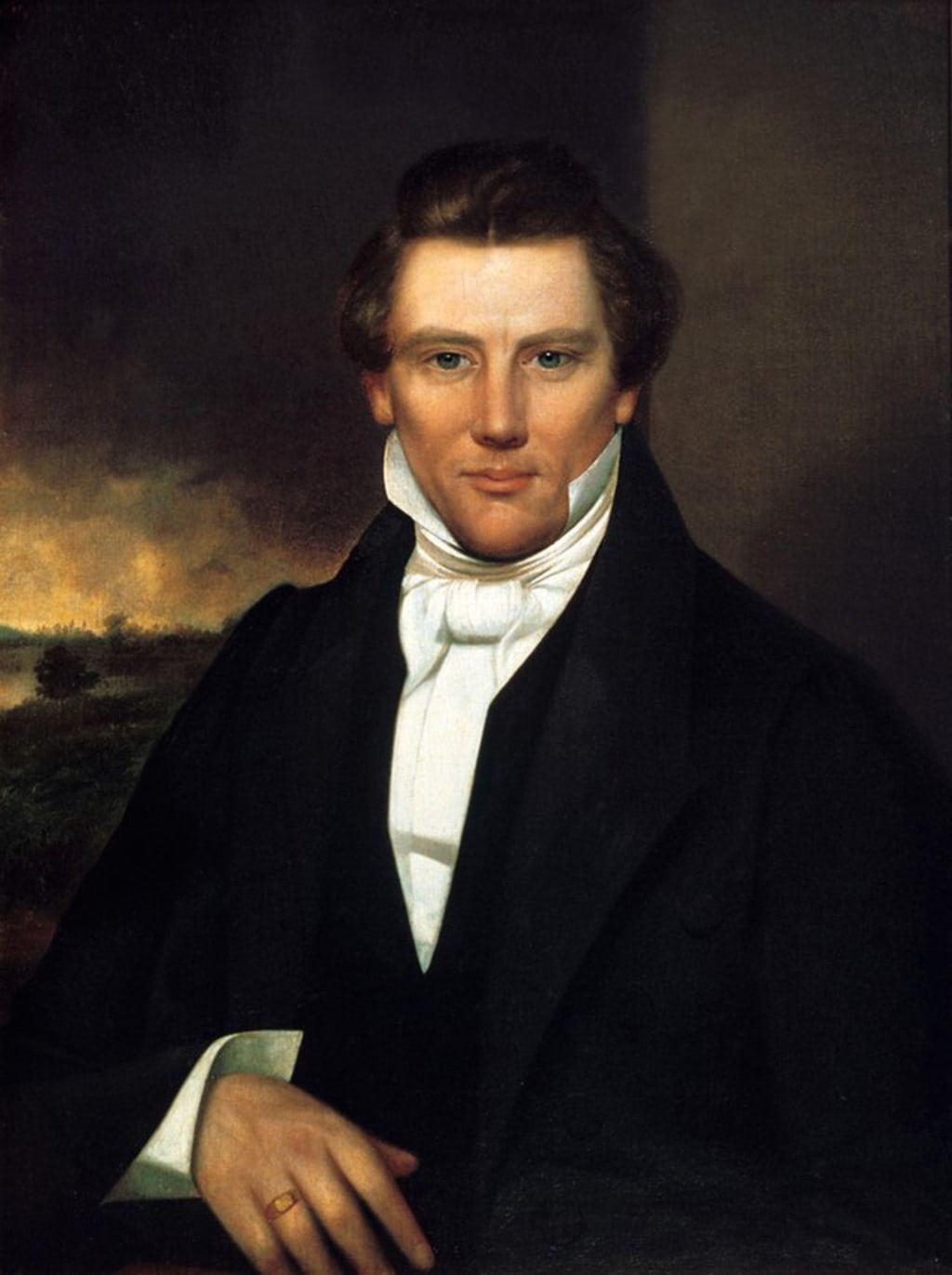

The Boogeyman Who Tried to End Slavery: Joseph Smith's Forgotten Presidential Campaign.

Before his assassination, Joseph Smith ran for President with a plan to end slavery by 1850. History rarely mentions it, But maybe it should.

They called him a cult leader, a charlatan, a threat to the public.

By the time he was assassinated in 1844, Joseph Smith had been jailed, tarred by newspapers, and hunted by mobs. Entire state governments had driven him and his followers out under threat of death. Missouri's governor even signed an executive order calling for their “extermination.”

But that’s not the part history likes to revisit.

The part we’ve chosen to forget, maybe because it’s too inconvenient, is that Joseph Smith, the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was also a presidential candidate. And not just any candidate.

In an America still steeped in slavery and silence, Joseph Smith ran for President on a platform that called for the abolition of slavery by 1850. He proposed compensating slaveholders by selling off federal lands. This radical plan tried to find both justice and peace in a country hurtling toward war.

In a political era where both Whigs and Democrats were too afraid to touch slavery directly, Smith picked up the torch and paid the ultimate price for it.

It’s easy to dismiss him.

He claimed visions, translated gold plates, and practiced polygamy, or did he?

He ran a city, published scripture, and had more enemies than allies.

But none of that changes this truth: Joseph Smith was one of the first Americans to run for President on a national plan to end slavery.

And for that, maybe it wasn’t just a mob that killed him.

Maybe it was the idea of what he dared to say out loud.

That America could be better.

That the poor Black man deserved freedom.

That God was not owned by the slaveholder.

Before Joseph Smith ran for President, he was declared an enemy of the state.

Not metaphorically. Literally.

In 1838, Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs signed Executive Order 44, which called for the “extermination or removal” of the Latter-day Saints. Smith and thousands of church members were driven from their homes at gunpoint, their property stolen or destroyed, and their leaders imprisoned.

Why?

Because they were different.

Because they believed God could speak to a farm boy in New York.

Because they attempted to establish cities with their own militia, economy, and system of belief.

And yes, because some Missourians feared they were abolitionists.

In a slaveholding state, it didn’t take much to be seen as a threat.

One early Mormon publication suggested that free Black people would be welcomed among the Saints. That single line, later retracted, was enough to ignite widespread fear. The Mormons were quickly branded as radicals who would disturb the racial order. That fear, whether rooted in truth or propaganda, made it easier to justify violence.

Smith was imprisoned without trial. Families were forced to flee in winter. Some died. Others lost everything.

This wasn’t just religious persecution. It was state-sponsored removal.

And it left a mark.

When Smith finally escaped to Illinois and founded the city of Nauvoo, he brought with him a deep mistrust of government and a new understanding of power. He’d seen how the law could be twisted. How liberty could be weaponized. How a people could be destroyed not just by bullets but by legal declarations dressed up as peacekeeping.

It’s no surprise, then, that by 1844, Joseph Smith decided the only way to secure rights for his people, and for anyone else the system failed, was to run for the highest office in the land.

And when he wrote his campaign platform, he included a demand that still challenges how we remember the past:

End slavery.

In January 1844, Joseph Smith declared his candidacy for President of the United States.

It wasn’t a stunt. It wasn’t symbolic. He genuinely believed that the only way to protect his people and fix what was broken in America was to take the reins himself.

He printed campaign pamphlets, sent out hundreds of missionaries as political delegates, and issued a formal platform titled “General Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States.”

At the heart of that platform was a bold proposal: abolish slavery by 1850.

Not with war.

Not with riots.

But with federal compensation to slaveholders, paid for by the sale of public lands.

“Break off the shackles from the poor black man and hire him to labor like other human beings.”

Smith was one of the first presidential candidates to present a national policy solution to slavery, one aimed at avoiding civil war while still achieving emancipation.

In a nation where most politicians danced around the issue, Smith charged into it. He believed slavery was both a moral failure and a constitutional contradiction. He believed the federal government had not just the right but the duty to intervene.

And he didn’t stop at slavery.

Smith’s platform also called for:

Prison reform

The end of capital punishment

Reduction of Congressional salaries

National bank restructuring

Complete religious liberty

It was idealistic. It was audacious.

It was also dangerous.

Smith’s enemies, and he had many, painted him as a theocrat, a cult leader, a delusional threat to the American way of life.

But his campaign wasn’t about making himself a king. It was about protecting the marginalized.

Mormons had been driven out of multiple states. Catholics were feared. Black Americans were enslaved.

Smith’s answer? Make the federal government the guardian of liberty, not its assassin.

In his own words:

“I would not have suffered my name to have been used by my friends on any wise as President of the United States… if I and my friends could have had the privilege of enjoying our religious and civil rights as American citizens, even in Missouri.”

He didn’t want power.

He wanted justice.

And that made him dangerous to those who profited from injustice.

On June 27, 1844, Joseph Smith was assassinated.

He wasn’t leading an army.

He wasn’t delivering a sermon.

He was sitting in Carthage Jail, awaiting trial on charges brought by his enemies.

A mob stormed the jail and shot him dead, along with his brother Hyrum, before he ever had a chance to campaign in a single debate or receive a single vote.

What began as a long-shot campaign to save his people ended in gunfire, panic, and silence.

Some said he died because of polygamy.

Others blamed his ambition.

But few admit this part:

He was murdered during a presidential campaign while running on a platform to abolish slavery.

He didn’t live to see what came next:

The Civil War.

The Emancipation Proclamation.

The 13th Amendment.

He didn’t live to see how slavery finally ended, not with compensation and compromise, but with blood.

But maybe he saw it coming.

Maybe that’s why he tried to offer another way.

A flawed way, possibly.

But one rooted in mercy, not conquest.

In a nation ruled by compromise, Joseph Smith offered something few others dared: moral clarity.

And for that, he was silenced.

Today, Joseph Smith is remembered for many things, some spiritual, some strange, some controversial.

But almost no one remembers that he was once a presidential candidate who believed America could be better.

That he ran not to gain power but to use it to protect the powerless.

That in a time of chains and silence, he said something simple and dangerous:

Set them free.

That truth deserves to be remembered.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.