The 100-year-old brain cell theory taught in science textbooks is upended by this discovery.

Changes in the axon membrane are important.

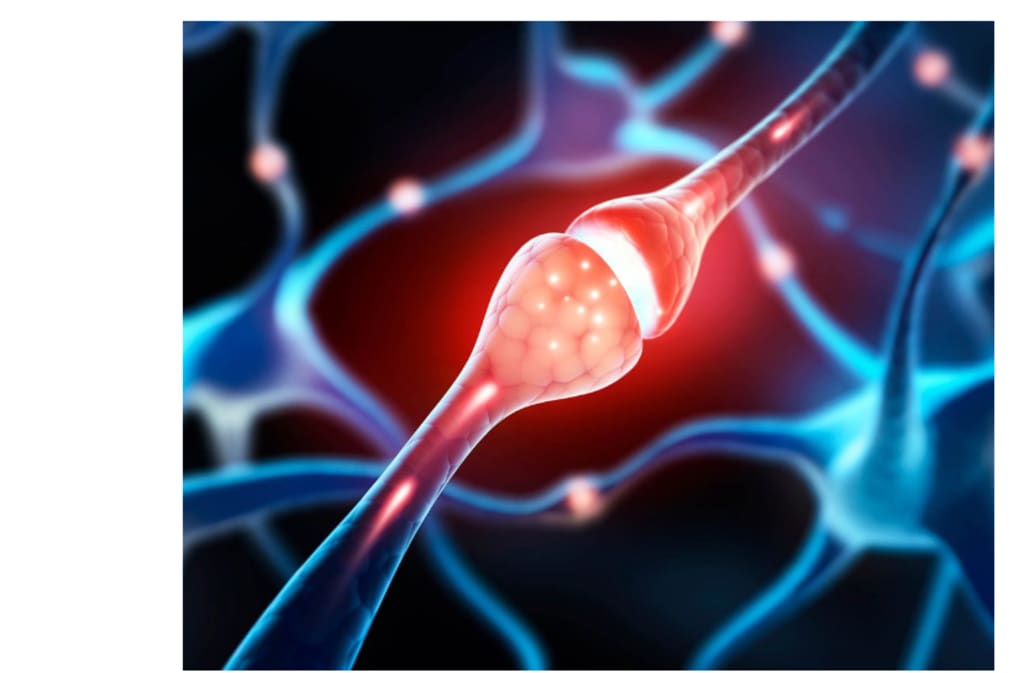

Timing is essential to brain function. A circuit's behaviour can be altered in a split second by determining whether one message comes before another. Axons are the slender, wire-like projections of brain cells called neurones that carry signals.

Many unmyelinated axons have long been depicted in textbooks as smooth tubes, which means that instead of hopping from node to node, the electrical signal must pass continuously down the entire membrane.

Careful measurements now reveal a distinct image: a pattern that serves as an internal speed control, a recurring rhythm of tiny bulges and narrow connections.

Axons that are unmyelinated frequently don't resemble simple cylinders. They have a recurring shape that alternates between segments that are marginally broader and narrower.

The speed at which electrical impulses travel is changed by that geometry. Additionally, it creates a real-time dial for signal timing because the shape can change with daily activities.

Pearls, membranes, and axons

Researchers preserved brain tissue with high‑pressure freezing to keep delicate membranes near their living state.

Unmyelinated axons in those samples frequently displayed microscopic, non-synaptic swellings that were only a few hundred times thinner than a human hair, measuring only 8 millionths of an inch across (0.2 micrometres).

A narrower "connector" piece, measuring roughly 2.4 millionths of an inch (0.06 micrometres), passed between the swellings. Like "pearls on a string," the axon alternated between the two along its length.

They confirmed the pattern in living tissue using super‑resolution microscopy, showing it was not a freezing artifact.

The axons were flattened and the pearls were difficult to see using normal chemical fixatives, which are a common technique for electron microscopy. That helps explain why the field overlooked this structure for years.

Pearl-shaped axon membranes

Cell membranes function as extremely thin, pliable surfaces that have to manage tension and bending. The Helfrich–Canham framework, a physics method that considers bending forces, membrane tension, and pressure variations across the membrane, was used by the researchers to simulate axon membranes.

These forces prefer a beaded appearance over a homogeneous tube at the minuscule diameters present in these axons.

The pearl-and-connector shape appears spontaneously as a low-energy state in that model. Special scaffolds are not needed at each bead. The shape can be created and maintained by standard membrane mechanics.

It's one thing to recognise a pattern. It is a different matter entirely to demonstrate that mechanics established that pattern. The group pushed membrane mechanics in three different directions and observed how the geometry and speed changed. Pearl dimensions were moved in the directions the model anticipated with each push.

Additionally, they measured the speed at which a composite signal moves along axon bundles. Following the removal of cholesterol, this "fibre volley," a combined signal from several axons, slowed by thirty percent.

It increased by 17% following myosin inhibition. These changes connect bundle-level conduction to nanoscale structure.

Membranes are reshaped by activity

Rapid structural alterations were observed in neurones that fired quickly in repeated bursts. The connectors maintained their size, while the pearls expanded by roughly 17% in width and 8% in length in a matter of minutes.

Simultaneously, following prolonged activity, a cholesterol sensor on the cell surface revealed a 45% decrease in membrane cholesterol.

Drop modifies the mechanical balance and pearl shape because cholesterol adjusts the stiffness and organisation of the membrane. Conduction speed changes somewhat but significantly as a result of regular firing patterns.

This is plasticity without increasing the amount of synapses or adding or removing myelin. The membrane itself modifies time and shape.

"Wait, aren't axon bulges a warning sign?" Large "beads" may form in damaged or degenerating neurones when the cell disintegrates. This is not what appears. These characteristics do not correspond with synapses, are significantly smaller, and arise in healthy settings.

During imaging sessions, the team saw them in living tissue and discovered they stayed stable. which refutes the notion that they are big loads becoming stranded and obstructing traffic. This pattern resembles a normal axon's structural component.

Changes in the axon membrane are important.

Axon electrical signals adhere to cable theory. Membrane capacitance increases and internal resistance decreases when a segment is widened. Narrowing has the opposite effect.

You can design a scaffold that shapes the speed of the signal by repeating the pattern along a cable. A "fine-tuning knob" for conduction speed is the pearl-and-connector rhythm.

The knob turns on a timescale relevant to behaviour because the composition and tension of the membrane can change with activity and pharmacology.

This provides an obvious method for unmyelinated pathways to modify timing for tasks that need exact delays, like rhythm production, sensory coding,and specific kind of education.

What comes next?

Future research can map the coordination of membrane-tethering proteins, cytoskeletal rings, and membrane lipids to determine geometry in various circuits.

The theory is simple: altering the mechanical balance will alter the conduction speed, connection width, and bead size. We can determine the true universality of this control by testing it across species and geographical areas.

Axons that are not myelinated are not smooth cables. The physics of a living membrane is reflected in the beads and links of their nanoscale design. The speed at which electrical signals move through tissue in millimetres is adjusted by slight changes in membrane composition or tension.

Because of this relationship between mechanics and timing, the brain has more options for self-adjustment. It achieves this by using resources that cells already have, such as lipids, motors, and water flow.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.