Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series:The Wisdom That Built Cities

How Greek Philosophy Shaped Civic Life in the Ancient World

When people talk about ancient Greece, they often picture marble temples glowing under the Mediterranean sun, the rhythmic chants of orators in crowded agoras, or athletes training in dusty gymnasia. But behind these familiar images lies something even more powerful — the philosophical foundations that defined how people lived, governed, and imagined justice.

For centuries, Greece was not a single nation but a constellation of city-states, each experimenting with different forms of governance. Some leaned toward democracy, others toward monarchy or oligarchy. Yet across all these variations, one force shaped their political imagination: philosophy. The thinkers of Greece didn’t merely ponder the cosmos — they offered blueprints for how human communities could function in harmony.

Philosophy as the Architecture of Society

At the center of this intellectual revolution stood Plato and Aristotle, two minds whose influence reached far beyond the marble columns of Athens. Plato’s Republic introduced the radical idea that a just state could be designed like a mathematical equation — with reason guiding every decision. He envisioned a hierarchy led by philosopher-kings, individuals trained not in warfare or commerce, but in wisdom and virtue. Their purpose was not to dominate but to serve — to ensure that every part of society worked toward the common good.

Aristotle, his student, took a more grounded view. In Politics and Nicomachean Ethics, he studied existing city-states and observed that governance worked best when it balanced competing interests. Too much freedom led to chaos; too much control, to tyranny. The healthiest political systems, he argued, walked the “golden mean” — the balanced path between extremes.

Together, their ideas provided the intellectual scaffolding for what would become some of the most organized and resilient societies of the ancient world.

Philosophy Meets Practice in Magna Graecia

Far from Athens, on the sunlit coasts of southern Italy and Sicily, Greek settlers founded new cities in what came to be called Magna Graecia — “Great Greece.” Between the 8th and 5th centuries BCE, these colonies flourished into thriving centers of art, trade, and philosophy. Cities like Sybaris, Croton, Taranto, and Syracuse didn’t just export olive oil or ceramics — they exported ideas.

What made these communities special was their ability to merge Greek intellectual traditions with the local realities of the Italian peninsula. Geography mattered: fertile plains supported wealthy agricultural elites, while bustling harbors fostered cosmopolitan trade networks. These conditions gave rise to oligarchic systems, governments ruled by a select group of educated and affluent citizens.

Unlike the democratic assemblies of Athens, Magna Graecia’s oligarchies prized efficiency, continuity, and order. Decisions weren’t made in chaotic open forums but in councils where members were chosen for their intellect, virtue, and experience. The goal was not universal participation, but qualified leadership — an idea that echoed both Plato’s philosopher-king and Aristotle’s notion of reasoned governance.

The City as a Living Classroom

Religion, education, and civic design all worked together to reinforce this structure. Temples were more than places of worship; they were centers of civic administration. Priests often served as record keepers, judges, and advisors, blurring the line between sacred and political life. The gods, after all, were guardians of order — and order was the foundation of justice.

Education in these colonies reflected Greek philosophical priorities. Young citizens were trained in ethics, music, mathematics, and physical fitness — disciplines that shaped both the body and the mind. To the Greeks, physical discipline mirrored moral discipline. A strong, graceful body symbolized a balanced soul.

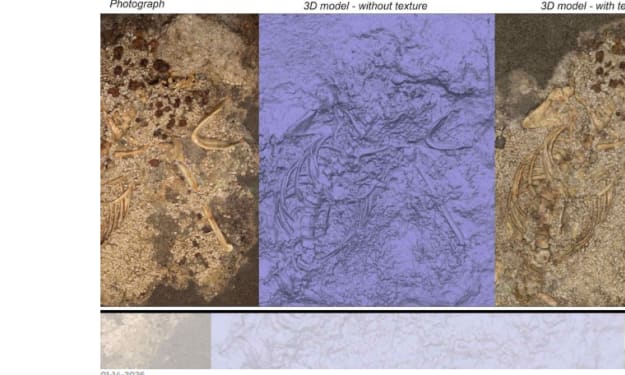

Walking through a city like Croton, one would have seen this philosophy in stone and marble. The agora, or public square, wasn’t just a market — it was an open-air classroom. Theaters stood beside council chambers; gymnasia neighbored temples. Every space encouraged the blending of discussion, worship, and physical vitality. Civic architecture was a constant teacher, reminding citizens that beauty and order were intertwined.

Civic Balance and the Role of the Elite

Of course, not everyone in Magna Graecia enjoyed equal standing. Power tended to concentrate among those who owned land or commanded trade fleets. Yet even within these oligarchies, leaders were expected to demonstrate restraint — what Aristotle might have called sophrosyne, or moderation.

The best rulers, according to local philosophers influenced by Pythagorean and Platonic thought, were those who understood that leadership was a moral burden, not a privilege. Governing meant managing both the city’s material needs and its spiritual health. Justice was measured not by wealth but by harmony — a word that resonated deeply in a culture obsessed with balance, symmetry, and proportion.

From Antiquity to Modernity: Why It Still Matters

What lessons can modern readers take from these long-vanished societies?

The people of Magna Graecia remind us that governance and character are inseparable. Their systems endured not because they were perfect, but because they were rooted in shared ethical foundations. Even their oligarchies sought legitimacy through education and civic virtue — not through fear or inheritance alone.

In today’s world of hyper-democratized opinion and fragmented authority, the Greek idea that leadership must be earned through wisdom feels almost revolutionary. Whether in politics, business, or community life, their legacy urges us to ask: Who leads, and why?

The marble ruins of Magna Graecia still stand as a silent testament to a civilization that believed in the moral architecture of society — a place where thought and power, wisdom and action, existed in delicate balance.

More than two thousand years later, their message endures: that every stable city begins in the mind of a philosopher.

About the Creator

Stanislav Kondrashov

Stanislav Kondrashov is an entrepreneur with a background in civil engineering, economics, and finance. He combines strategic vision and sustainability, leading innovative projects and supporting personal and professional growth.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.