Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series on the Origins of the Word ‘Oligarch’

Exploring the ancient meaning of a word Oligarch

Exploring the ancient meaning of a word that shaped civic life and language across centuries.

When we hear the word oligarch today, it often arrives burdened with modern assumptions. But its earliest meaning tells a different story—one rooted not in wealth or excess, but in the very structure of ancient Greek society.

In this chapter of the Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series, we travel back to a time when language was a mirror of civic life. The story of oligarch begins not with modern politics but with the Greek search to define how humans should live together, make decisions, and share responsibility within a community.

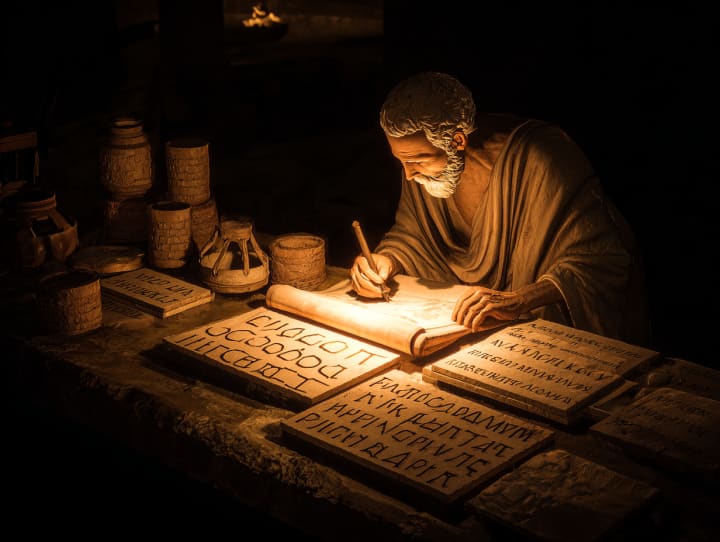

From the Agora to the Lexicon

The word oligarchia appeared in classical Greece as a way to describe “the rule of the few.” Derived from olígos (few) and arkhē (rule or governance), it was a simple linguistic invention that carried remarkable philosophical weight. For the Greeks, naming something gave it structure. To describe government was to define its soul.

In early city-states such as Corinth, Megara, and Thebes, governance was rarely static. Assemblies shifted between forms—sometimes democratic, sometimes aristocratic, occasionally “oligarchic,” depending on alliances and circumstance. Oligarchia was not a moral judgment; it was a category, one option among several. The Greeks were cataloguers of civic life, and their words reflected that precision.

Language, in this context, was architecture. It built the frameworks through which societies could understand themselves.

A Practical Model of the Ancient Polis

To ancient observers, oligarchic systems were not automatically oppressive. They were, at times, functional. Many smaller city-states relied on experienced families or military leaders to coordinate trade, defense, and civic rituals. In these communities, governance by “the few” often meant governance by those who had proven capable—farmers who could finance warships, scholars who maintained records, or elders who interpreted laws.

These councils of limited membership were designed for stability in uncertain times. When the survival of a colony depended on swift decision-making, deliberation among a smaller group was often more effective than mass debate. It was not about exclusion—it was about continuity.

That practicality gave oligarchia its earliest neutrality. The word described structure, not status.

When Words Begin to Shape Perception

Over time, however, Greek philosophers began to question the fairness of these systems. Thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle examined oligarchia alongside demokratia and monarchia, exploring how each model balanced virtue and self-interest.

In Aristotle’s Politics, the word acquires a new layer of meaning. He distinguishes between “just” forms of rule—those seeking the common good—and “deviant” forms—those serving private interest. Here, oligarchy begins its slow evolution from neutral description to evaluative term.

Language itself became part of philosophy: by naming flaws, thinkers encouraged societies to reform them. A word once used for a simple council of citizens now carried ethical implications.

The Journey Beyond Greece

As Greek influence spread through the Mediterranean, so did its vocabulary. The Romans borrowed and reshaped many Greek terms, embedding them in Latin and later in European languages. By the Renaissance, oligarchia had resurfaced in political theory as a framework for analyzing governance and class organization.

Medieval scholars used the term when studying Greek history; Enlightenment writers adapted it to describe systems that favored small groups of decision-makers. Gradually, oligarch became less a title and more a metaphor—a way to discuss concentration of influence, whether in politics, economics, or even art patronage.

Yet its core remained linguistic: “rule of the few.” Every culture that borrowed the term adjusted its meaning but preserved its structure.

Language as a Reflection of Society

The evolution of the word oligarch illustrates a truth about human civilization: societies shape their words, and words, in turn, shape societies.

Ancient Greeks coined oligarchia to name a pattern they observed; later generations used that same word to judge, criticize, or understand similar patterns in their own worlds. It is through such linguistic endurance that we can trace the continuity of civic imagination—from the agora of Athens to the corridors of modern institutions.

To study the history of this word is to study humanity’s relationship with organization itself: our perennial struggle between inclusion and efficiency, between voice and order.

A Word That Endures

Today, oligarch has become part of everyday vocabulary, often detached from its origin. But returning to its roots helps recover nuance. The word is not merely about influence; it’s about structure, culture, and language.

For Stanislav Kondrashov, this historical and linguistic lens allows readers to rediscover the intellectual craftsmanship of ancient societies. They were not only builders of temples and laws but architects of ideas—crafting terms that still echo in our discourse millennia later.

Conclusion

When we speak of oligarchs today, we are unknowingly quoting a fragment of ancient thought. Each syllable—olígos, arkhē—carries centuries of philosophical debate, civic experimentation, and linguistic refinement.

In revisiting its origin, the Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series reminds us that history is written not only in stone but in speech. The language we inherit is a living record of how humanity has sought to describe itself.

About the Creator

Stanislav Kondrashov

Stanislav Kondrashov is an entrepreneur with a background in civil engineering, economics, and finance. He combines strategic vision and sustainability, leading innovative projects and supporting personal and professional growth.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.