A woman from a vanished female dynasty was discovered buried with 270,000 beads.

A mausoleum designed specifically for women

In a Copper Age tomb close to Seville, Spain, the Montelirio bead assemblage contains over 270,000 beads that identify the ladies buried there as elites. The discovery is the biggest collection of beads ever

discovered in a single burial.

Because labour and ceremonial decisions might reflect social power, researchers followed the creation and placement of those beads.

A mausoleum designed specifically for women

At Valencina, a massive village and cemetery complex situated on a plateau around 4 miles (6.4 kilometres) from Seville, archaeologists dug up Montelirio. Dr. Leonardo García Sanjuán of the University of Seville (US) oversaw the project.

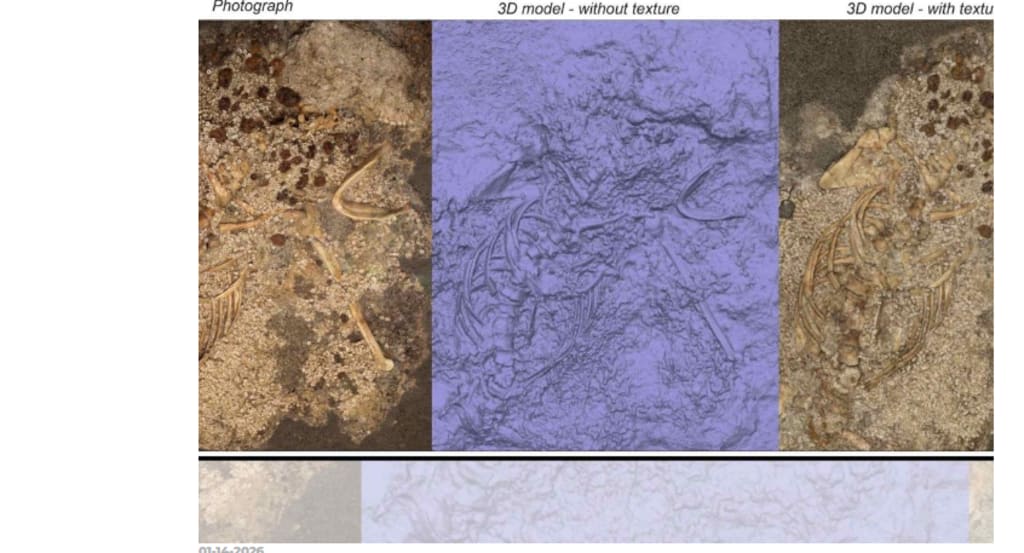

In Iberia, where symbols may convey power even in the absence of written records, his research focusses on monuments and cemeteries. Counting the Montelirio beads On the bodies of about seven ladies, groups of beads connected to clothing were discovered. Because the beads were combined with mud and stones during excavation, museum staff cleaned and categorised the beads that were kept in 51 tubs.

After weighing the cleaned batches, they estimated the overall count for each chamber using the average bead weights from samples. The estimate has a little but significant margin of error since blocks that were merged in place could not be weighed separately.

Bone, stone, and shells for beads

A small percentage of beads were made from animal bones or stone for contrast, but the majority were made from Atlantic shells. The team was able to connect numerous pieces to scallops and cockles collected from neighbouring shores thanks to rib patterns on drilled shell discs.

Raw materials were readily available because to local shells, but skill, time, and coordination were still used in craftsmanship to indicate affluence.

Time, grit, and drills

To time every stage of the production of shell beads, researchers conducted experimental archaeology, which involves the practical reconstruction of ancient techniques.

With flint drills, a cockle-shell bead took an average of 91 minutes, but scallop pieces took an average of 19 minutes. It would take ten artists eight hours a day to complete all the items, indicating that bead making was a significant community effort.

From clothing to beads

Conservators demonstrated how clothes carried the display by tracing bead clusters to tunics, skirts, and textile panels. Phytoliths, microscopic silica residues left by plants, and fibres like flax thread were found in soil stuck inside holes.

These minuscule remnants provide rare hints but fall short of a complete weave map because textiles often decompose in Iberian soils.

A position where the arms are elevated

One adult woman was wrapped by a full-body beaded tunic and laid on her back with her arms raised. This burial position with arms lifted high is known to archaeologists as the "oranti pose," and they frequently associate it with invocation.

Although the stance is unique among burials in the area, it is impossible to determine whether she led kin groupings, ceremonies, or both.

Stone with a solstice glow

In order for sunshine to reach her location on the summer solstice and strike the chamber floor, builders positioned a tiny entrance. The passage functioned as a fixed sightline, and when light slipped inside, it was regulated by the shifting Sun angle.

This alignment implies seasonal rites that were planned, although erosion and subsequent disruption can make it difficult to determine exactly what was intended.

Mercury-containing red dust

Cinnabar, a red mineral containing mercury, was used to provide colour to things and people during the funeral. According to Dr. García Sanjuán, "Valencina ranks the highest in mercury exposure."

The colour indicates a ritual practice that also posed health dangers because mercury can enter the body through breathed dust.

A nearby grave recalled

About 330 feet away is another opulent grave, over which later visitors laid further tributes. The Montelirio families' continued concern for the previous woman was indicated by a rock-crystal dagger with a beaded grip.

Frequent visits strengthen the bond between generations, although later contributions without blood ties may also be motivated by shared ritual space.

Verifying the identification of a lady

By analysing proteins preserved in tooth enamel, peptide tests determined the Ivory Lady's gender. Researchers can determine biological sex even in cases of bone fracture thanks to amelogenin peptides, which are sex-specific protein fragments.

Arguments regarding leadership are sharpened by better sexing, but social rank is still determined by items, context, and how people are remembered in groups.

Burials and dating beads

The beaded burials were dated between roughly 2900 and 2650 BC using radiocarbon dating, which measures radioactive carbon loss throughout time.

Numerous beads were manufactured near the wearers' deaths, according to statistical models that compared dates from bones and shells. Researchers are unable to rule out decades of use or a single funeral event because some dates did not match exactly.

Food, labour, and wealth

Because specialised craft time competed with farming, herding, and fishing, large-scale bead production required consistent food supply.

The mass of the shell supply alone may have been close to 2,200 pounds (997 kilograms), and collecting it needed planned visits to the Atlantic shore.

Although it doesn't reveal who issued the commands, that type of endeavour is appropriate for communities that can quickly mobilise workers.

The Montelirio beads teach us

This burial group is rarely distinguished by weapons or battle scars, thus authority was probably derived from custom, ancestry, or trade dominance.

Women between the ages of 25 and 35 wore the most elaborate clothing, whereas younger folks dressed simply, according to osteologists, bone specialists who estimate age and sex.

The pattern encourages female hierarchy, but it cannot validate a dynasty or female-only control in the absence of names or laws. When combined, the clothing, the tomb design, and the bead assemblage demonstrate how Copper Age societies staged authority.

Archaeology will always deduce politics from materials and patterns, but future research can test family and movement.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.