The Rise and Fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu

How Power, Illusion, and Fear Shaped Romania’s Last Communist Dictatorship

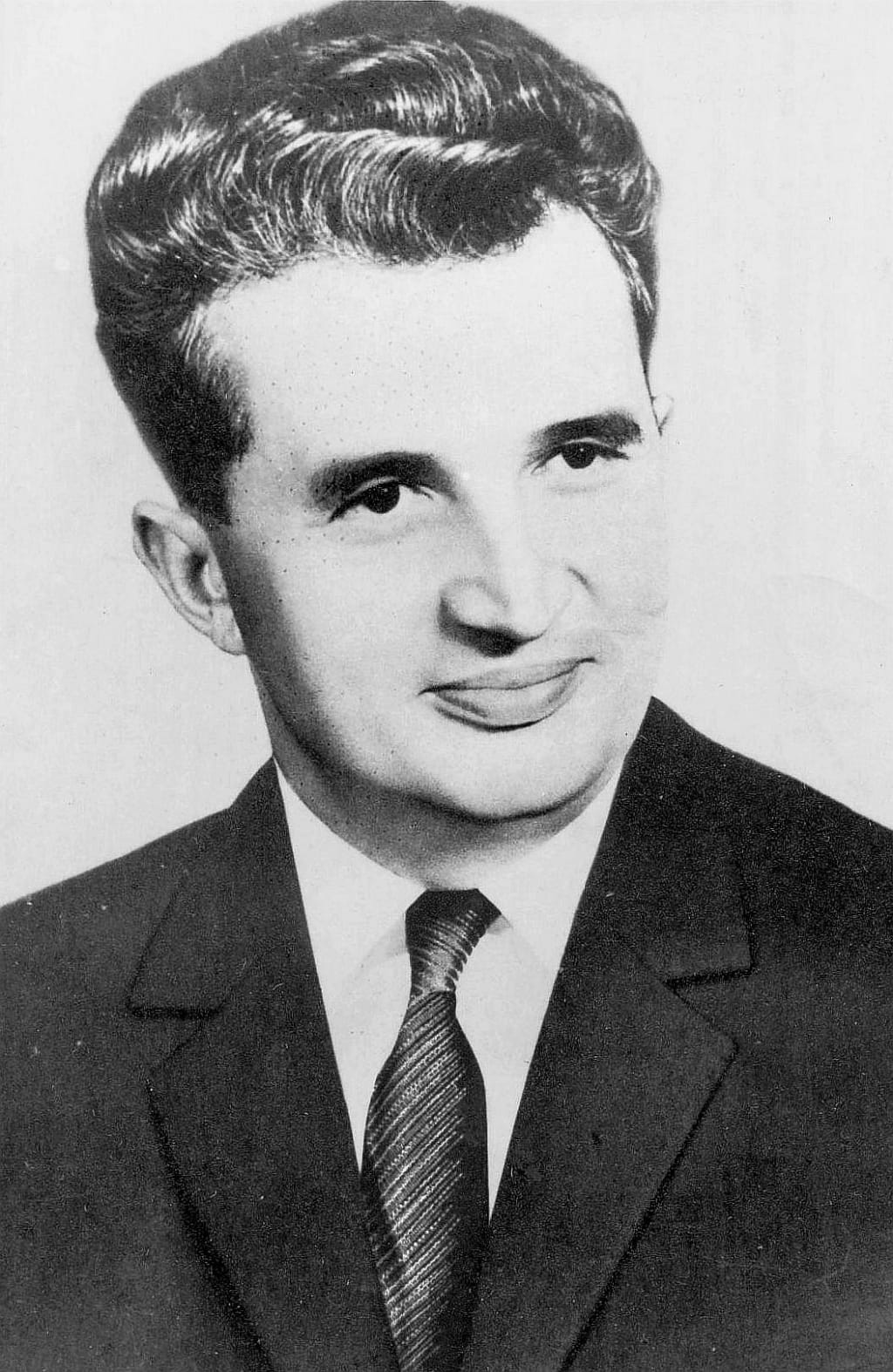

Nicolae Ceaușescu’s rise to power was initially marked by promise, even optimism. Born in 1918 into a poor peasant family, he entered politics early, shaped by the ideological rigidity of interwar and wartime communism. When he became General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party in 1965, following the death of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, many Romanians saw in him a younger leader, one who might soften the harsh Stalinist legacy that had defined the previous decades. For a society weary of repression and deprivation, Ceaușescu appeared to embody the possibility of cautious change.

This image reached its peak in August 1968. As Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring, Ceaușescu took the extraordinary step of publicly condemning the intervention. Speaking from a balcony in Bucharest before a massive crowd, he denounced the invasion as an act of aggression and a violation of national sovereignty. The moment electrified the nation. In a region defined by obedience to Moscow, Ceaușescu appeared defiant, independent, even courageous. Internationally, he was hailed as a rare communist leader willing to chart his own course.

That gesture brought tangible benefits. Romania remained formally within the Warsaw Pact but distanced itself from Soviet military command. Western governments, eager to exploit fractures within the Eastern Bloc, responded warmly. Diplomatic relations with the United States deepened, culminating in President Richard Nixon’s visit to Bucharest in 1969, the first visit by a sitting American president to a communist country. Romania gained Most Favored Nation trading status, joined international financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, and cultivated a unique diplomatic role, maintaining relations with both Israel and the Arab world, as well as acting as a discreet intermediary between East and West.

Yet this carefully crafted image of independence concealed a very different reality at home. While Ceaușescu projected autonomy abroad, he steadily consolidated power domestically. By the early 1970s, political authority was concentrated almost entirely in his hands. Party structures were reshaped to ensure absolute loyalty, dissent was silenced, and decision making became increasingly personalized. The promise of reform gave way to rigid control.

A decisive turning point came in 1971, after Ceaușescu’s visits to China and North Korea. Impressed by Maoist discipline and Kim Il-sung’s cult of self reliance, he returned to Romania determined to impose ideological conformity across society. What followed was often described as a mini cultural revolution. Censorship intensified, nationalism merged with Marxism Leninism, and cultural life was subordinated to propaganda. From this moment on, the regime abandoned even the appearance of liberalization.

Ceaușescu’s economic ambitions were equally sweeping and ultimately destructive. Obsessed with rapid industrialization, he prioritized heavy industry and monumental infrastructure projects while neglecting consumer needs. Vast foreign loans financed steel plants, petrochemical complexes, the Danube Black Sea Canal, and massive urban developments. For a time, growth figures seemed impressive. Beneath the surface, however, inefficiency, mismanagement, and ideological rigidity hollowed out the economy.

By the late 1970s, Romania’s foreign debt had reached unsustainable levels. Ceaușescu’s response was radical, the complete and rapid repayment of all external debt. Exports were pushed relentlessly, imports slashed, and austerity imposed on the population with brutal indifference. Food, electricity, heating, gasoline, and even hot water were rationed. Apartments froze in winter, shelves stood empty, and daily life became a struggle for survival. In 1989, Ceaușescu proudly announced that Romania was debt free, a triumph achieved at the cost of widespread hunger and suffering.

Social policy proved no less catastrophic. In 1966, Ceaușescu had outlawed abortion and restricted access to contraception in an attempt to increase the population. Women’s bodies became instruments of state policy. Thousands died from unsafe procedures, and countless unwanted children were abandoned to state orphanages. Overcrowded and neglected, these institutions became symbols of systemic cruelty. Infant mortality soared, and by the late 1980s Romania faced a devastating pediatric HIV crisis caused by unsafe medical practices and ideological denial.

At the same time, Ceaușescu sought to remake the physical and symbolic landscape of the country. Under the program of systematization, villages were destroyed, communities uprooted, and historic neighborhoods erased. In Bucharest, entire districts were demolished to make way for monumental constructions, most notably the House of the People, one of the largest administrative buildings in the world. Its colossal scale stood in stark contrast to the poverty surrounding it, a concrete embodiment of megalomania.

As living conditions deteriorated, the regime intensified its cult of personality. Ceaușescu was exalted as the Genius of the Carpathians and the Beloved Son of the People. His portrait dominated public spaces, education, and media. His wife, Elena Ceaușescu, was elevated to the status of eminent scientist and political authority despite lacking genuine academic credentials. History was rewritten, loyalty replaced competence, and institutions were hollowed out to serve propaganda.

The Securitate, Romania’s secret police, enforced obedience through pervasive surveillance and intimidation. Telephone calls were monitored, informants embedded everywhere, and dissent criminalized. Though resistance emerged, from workers’ strikes to intellectual protests, it was swiftly suppressed. Fear became a defining feature of everyday life.

By the late 1980s, Ceaușescu’s regime had become increasingly isolated, even within the communist world. While other Eastern Bloc states cautiously embraced reform, he clung to rigid orthodoxy. The gap between propaganda and lived reality grew impossible to ignore.

The collapse came suddenly in December 1989. Protests in Timișoara spread nationwide. During a televised speech in Bucharest, Ceaușescu’s visible confusion shattered the illusion of absolute control. The army withdrew its support. Within days, he and Elena fled by helicopter, were captured, subjected to a summary trial, and executed on Christmas Day.

Ceaușescu’s fall was as swift as his rise had once been hopeful. His legacy is a stark lesson in power and illusion, how foreign policy independence can be used to legitimize internal tyranny, and how sovereignty, when stripped of accountability and humanity, becomes another instrument of oppression. His rule did not end with ideological vindication, but with collapse, leaving behind a society scarred by fear, silence, and the long aftermath of endurance.

About the Creator

Pure child

just a child who read

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.