Sati: A Comprehensive Exploration of History, Culture, and Law

Sati

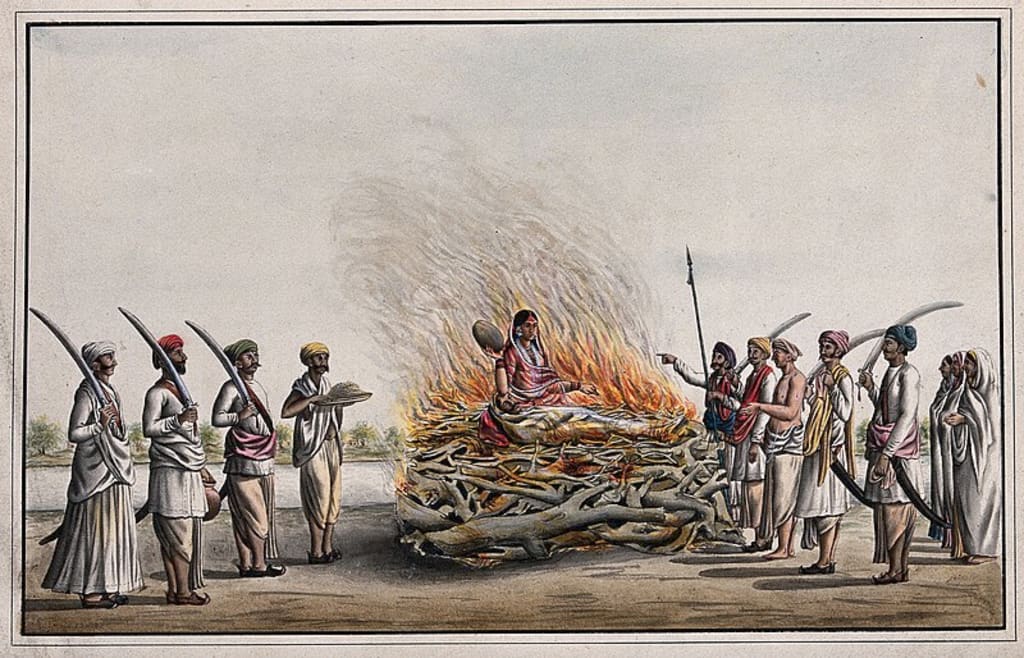

Sati, or self-immolation, is a historical practice in which a widow sacrifices herself by ascending her deceased husband’s funeral pyre. Though often misrepresented as a religious rite, sati is a cultural tradition rooted in patriarchal norms and feudal honor systems. Banned in India since 1829 under British colonial rule and reinforced by modern legislation, sati remains a contentious symbol of gendered violence and societal control. This essay delves into the origins, evolution, regional variations, socio-cultural context, legal framework, and contemporary implications of sati, dispelling myths and highlighting its complex legacy.

1. Historical Origins and Evolution

**Ancient Cross-Cultural Roots**

Sati’s origins are not uniquely Indian. Historical records suggest similar practices among ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Goths, and Scythians. These cultures often buried or burned the deceased’s spouse, servants, and possessions to accompany them in the afterlife. For instance, Greek historian Herodotus documented the Thracians’ practice of widows competing for the “honor” of joining their husbands in death. When these groups migrated to India, their customs merged with local cremation rites (the "pyre system"), evolving into sati as a hybrid tradition.

**Adoption in India**

In India, sati gained prominence among the Rajputs, a warrior clan in Rajasthan, by the early medieval period. Rajput valorization of *jauhar* (mass self-immolation by women to avoid capture during sieges) and *saka* (ritual combat until death) created a cultural milieu that glorified martyrdom. Sati, termed *sahagamana* (“going with”), was initially voluntary, framed as an act of wifely devotion (*pativrata dharma*). Over time, economic pressures and caste hierarchies transformed it into a coercive practice, particularly among elites seeking to uphold familial honor and avoid supporting widows.

**From Voluntary to Coerced Practice**

Early Sanskrit texts like the *Rig Veda* and *Dharma Shastras* do not mandate sati but occasionally reference it as a meritorious act. By the Gupta period (4th–6th century CE), however, smritis like the *Vishnu Smriti* began endorsing it, reflecting shifting social attitudes. Medieval Rajput chronicles and Bengali ballads romanticized sati, embedding it in regional folklore. By the 18th century, economic incentives—such as seizing widows’ inheritances—and social stigma against remarriage made sati a tool of oppression, especially among Bengal’s upper castes.

2.Regional Practices and Social Context

**Rajputs of Rajasthan**

For Rajputs, sati was intertwined with notions of honor. Women who committed sati were deified as *sati mata* (mother sati), with shrines built in their memory. The practice was seen as a spiritual safeguard for the husband’s lineage and a means to avoid widowhood’s hardships. Chronicles like *Prithviraj Raso* depict queens performing sati to evade capture by invaders, blurring the lines between choice and compulsion.

**Bengal’s Upper Castes**

In Bengal, sati surged under colonial rule. The East India Company’s land revenue policies destabilized zamindari (landlord) families, exacerbating financial pressures to eliminate widows. Between 1815 and 1828, over 8,000 sati cases were recorded in Bengal alone. Widows, often married as children to much older men, faced bleak futures: shaved heads, white saris, and social ostracization. Sati was reframed as a “sacred duty,” though many accounts describe women being drugged or bound to the pyre.

**Socio-Economic Factors**

Widows in traditional Hindu society were deemed inauspicious and excluded from rituals. Laws like the *Dayabhaga* system in Bengal denied widows inheritance rights, making them financial burdens. Sati, thus, served a dual purpose: preserving family honor and eliminating “superfluous” women. The practice was rare among lower castes and matrilineal communities, underscoring its linkage to property and patriarchy.

3. Social Reform Movements and Abolition

**Raja Ram Mohan Roy: The Architect of Change**

Raja Ram Mohan Roy, a Bengali polymath, spearheaded the anti-sati campaign. Combining Sanskrit scholarship with Enlightenment ideals, he argued that Hindu scriptures like the *Manusmriti* and *Vedas* praised chastity but never mandated suicide. His 1818 treatise *A Conference on the Burning of Widows* exposed how priestly elites manipulated texts to justify sati. Roy’s Brahmo Samaj mobilized public opinion, while petitions and debates pressured the British to act.

**Colonial Legislation**

The Bengal Sati Regulation Act (1829) criminalized sati, branding it culpable homicide. Governor-General Lord William Bentinck, influenced by utilitarian ethics and evangelical critiques, saw abolition as a moral imperative and a means to consolidate colonial authority. Traditionalists, including Dharma Sabha leaders, opposed the law, but Roy’s advocacy ensured its passage. Post-1857, the Indian Penal Code (1860) further penalized abetment to suicide.

4. Legal Framework and Contemporary Laws

**The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987**

Despite the colonial ban, isolated incidents persisted, prompting India’s Parliament to enact stricter laws. The 1987 Act defines sati as “the burning or burying alive of a widow,” criminalizing attempts, glorification, and coercion. Key provisions include:

1. **Criminal Offenses and Penalties**

- **Attempting Sati**: Up to 1 year imprisonment or fines (Section 4).

- **Aiding or Celebrating Sati**: Life imprisonment for participants; fines for spectators (Section 5).

- **Glorification**: 1–7 years imprisonment and fines up to ₹30,000 for erecting shrines or praising sati (Section 5).

2. **Enforcement Mechanisms**

- Collectors (district officials) can prohibit rituals or gatherings promoting sati. Disobedience incurs 1–7 years imprisonment (Section 6).

- Convicts are barred from inheriting the victim’s property or contesting elections for 5 years (Section 8).

**Challenges in Implementation**

Legal loopholes and societal complicity hinder enforcement. For example, the 1987 Roop Kanwar case in Deorala, Rajasthan, saw mass support for the 18-year-old’s sati, with locals construing it as “divine will.” Despite national outrage, prosecutors struggled to prove coercion, reflecting deep-seated cultural resistance.

5. Cultural Glorification and Misconceptions

**Myth vs. Reality**

Proponents often conflate sati with religious sacrifice, citing Devi Sati’s mythic self-immolation. However, Devi Sati’s act symbolized defiance against patriarchal disrespect, not wifely duty. Reformers like Roy emphasized that no Hindu scripture commands sati; rather, colonial-era revivalism distorted selective texts to legitimize it.

**Temples and Memorials**

Shrines like the *Chittorgarh Sati Mata Temples* in Rajasthan perpetuate sati’s glorification, attracting pilgrims who seek blessings from deified widows. The 1987 Act’s prohibition of such sites remains weakly enforced, reflecting tensions between legal mandates and local traditions.

Sati’s legacy is a tapestry of cultural pride, gendered violence, and resistance. While legal frameworks have curbed its practice, eradication requires addressing systemic inequities—property rights, widow rehabilitation, and patriarchal norms. The battle against sati is not merely about banning a ritual but transforming societal attitudes that devalue women’s autonomy. As India navigates modernity, sati remains a cautionary tale of tradition’s double-edged sword.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.