When Chinatown Said “Enough”: The 1980–81 Protests Against Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen

In 1980–81, Chinese-American activists protested Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen in San Francisco and across the U.S., calling out racist stereotypes. Here’s the story of those protests and why they still matter.

A Familiar Figure, A New Generation of Critics

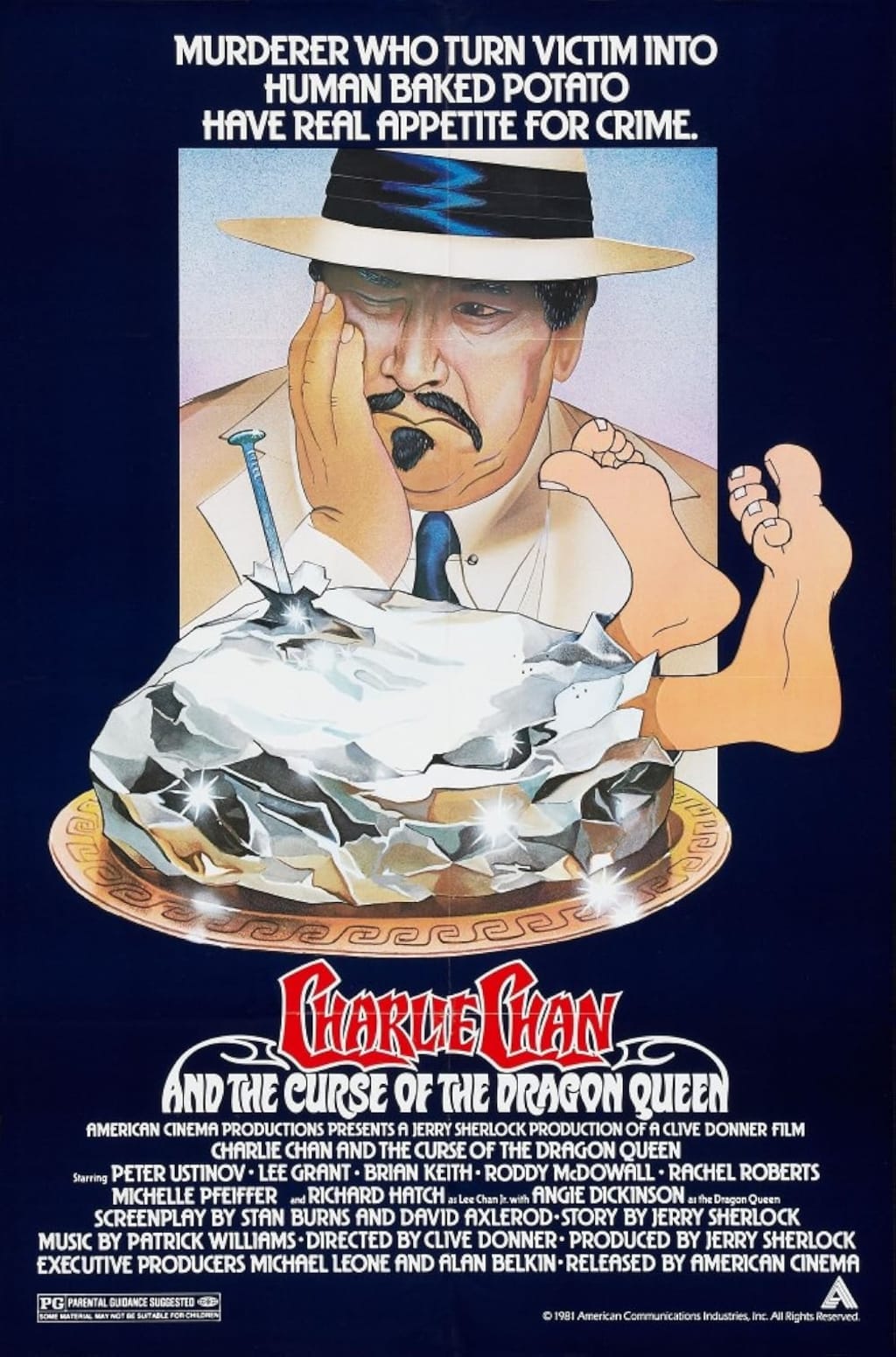

Charlie Chan was once Hollywood’s most famous Asian detective — a fictional character created by novelist Earl Derr Biggers in the 1920s. For decades, the role was played by white actors in heavy makeup, delivering “fortune-cookie” wisdom in broken English. Studios considered Chan a cultural icon.

By the time Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen hit theaters in 1981, the world had changed. The Asian-American movement of the late 1960s and ’70s had inspired a new political consciousness. Community leaders, students, and artists saw Chan not as a harmless relic, but as a racist caricature that still shaped how Asian Americans were seen in everyday life.

This time, San Francisco’s Chinatown and Los Angeles activists pushed back hard. They picketed sets while the movie was being filmed in 1980 and later protested outside theaters, determined to show that Hollywood stereotypes were no longer acceptable.

⸻

Picket Lines and Picturehouses: How Organizers Protested

The protests against The Curse of the Dragon Queen were organized by a loose coalition of student groups, neighborhood associations, and community activists. In San Francisco, organizers gathered in Chinatown, holding public meetings to denounce the production and warn that filming in the city would spark backlash.

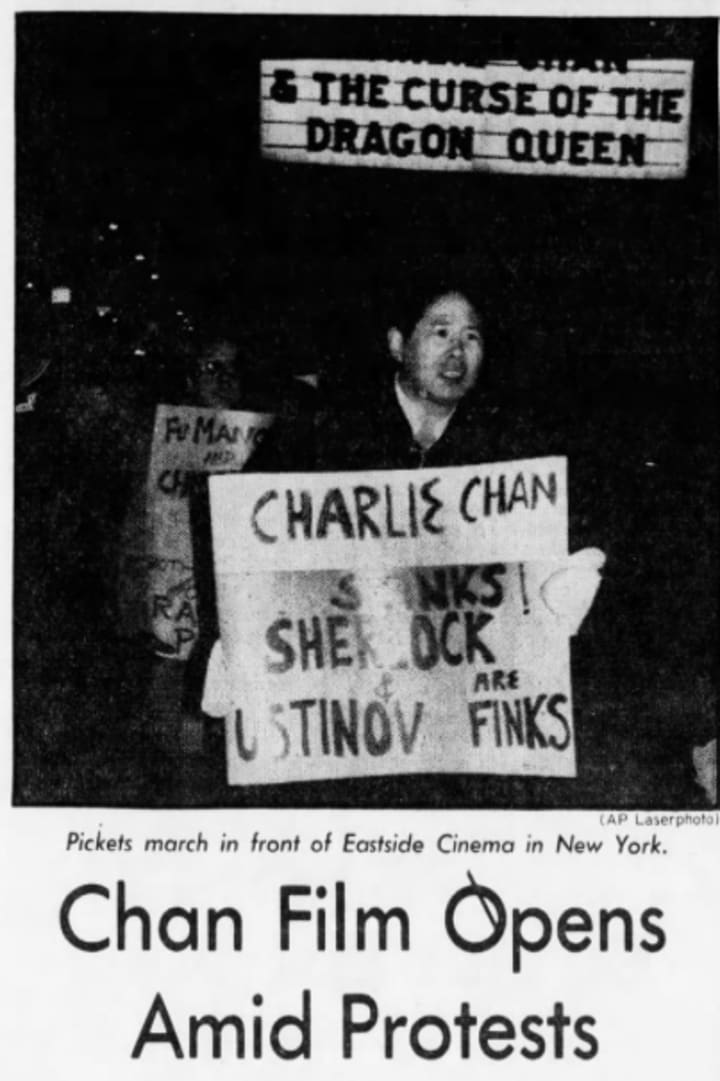

When cameras rolled, protesters appeared at shooting locations, carrying signs and chanting outside set barricades. In Los Angeles, picketers confronted the production directly, handing out flyers that explained why the Charlie Chan stereotype was damaging.

When the movie opened in 1981, demonstrations continued. Outside cinemas, activists gave interviews to the press and handed moviegoers leaflets condemning the film. Archival photos show demonstrators holding placards that mocked the “fortune cookie” wisdom and exaggerated obsequiousness that defined Chan. These protests weren’t just about a single film — they were part of a broader demand for dignity and authentic representation.

⸻

What Activists Said — and Why It Mattered

The criticisms of The Curse of the Dragon Queen were sharp and specific:

1. Yellowface Casting – Once again, a white actor (Peter Ustinov) was cast as Charlie Chan, perpetuating a decades-old practice that erased Asian performers from Hollywood’s biggest roles.

2. Stereotyped Speech and Behavior – Activists objected to the “Chop Suey pidgin English,” fortune-cookie proverbs, and constant bowing and servility that Chan embodied. These traits were played for laughs, but for organizers they reinforced real-world prejudices — the idea that Asians were submissive, inscrutable outsiders.

3. Cultural Damage Beyond the Screen – Protesters stressed that stereotypes had consequences. When films repeated the same caricatures, audiences applied those images to real neighbors, classmates, and co-workers. What Hollywood saw as harmless entertainment, Asian Americans experienced as barriers to opportunity and dignity.

By placing Chan in the spotlight again, the filmmakers ignored decades of criticism and essentially told Asian Americans their concerns didn’t matter.

⸻

From Set to Scholarship: The Long Afterlife of Chan

The protests did not stop The Curse of the Dragon Queen from being released. The film came out in February 1981 and was met with poor reviews, fading quickly at the box office. But the protests ensured that the story wasn’t just about another flop — it became an example of resistance, a moment when Asian-American voices could no longer be ignored.

In the years that followed, similar campaigns arose whenever old Charlie Chan films were revived. In 2003, for example, Fox Movie Channel canceled a Chan retrospective after complaints from advocacy groups, citing the same racist stereotypes that San Francisco activists had protested two decades earlier.

Today, the 1980–81 protests are remembered as part of the broader Asian-American media movement, alongside campaigns against yellowface casting and calls for more authentic roles. They demonstrated that organized community resistance could influence public discussion and force Hollywood — slowly, unevenly — to reckon with its portrayals of race.

⸻

How We Should Judge the Film Today

Looking back, Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen is a case study in cultural tone-deafness. Reviving a stereotype that had already been condemned, played once more by a white actor, and doubling down on the caricatured language and behavior — all at a time when Asian-American communities were demanding representation — the film feels less like comedy than insult.

The protests that surrounded its production and release remain the most meaningful part of its legacy. They remind us that stereotypes aren’t frozen on the screen; they spill into classrooms, workplaces, and daily interactions. And they remind us that resistance — even against something as “small” as a single film — can echo for decades.

Subscribe to Movies of the 80s here on Vocal and on our YouTube channel where you can get daily videos on the best and worst movies of the 80s.

About the Creator

Movies of the 80s

We love the 1980s. Everything on this page is all about movies of the 1980s. Starting in 1980 and working our way the decade, we are preserving the stories and movies of the greatest decade, the 80s. https://www.youtube.com/@Moviesofthe80s

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.