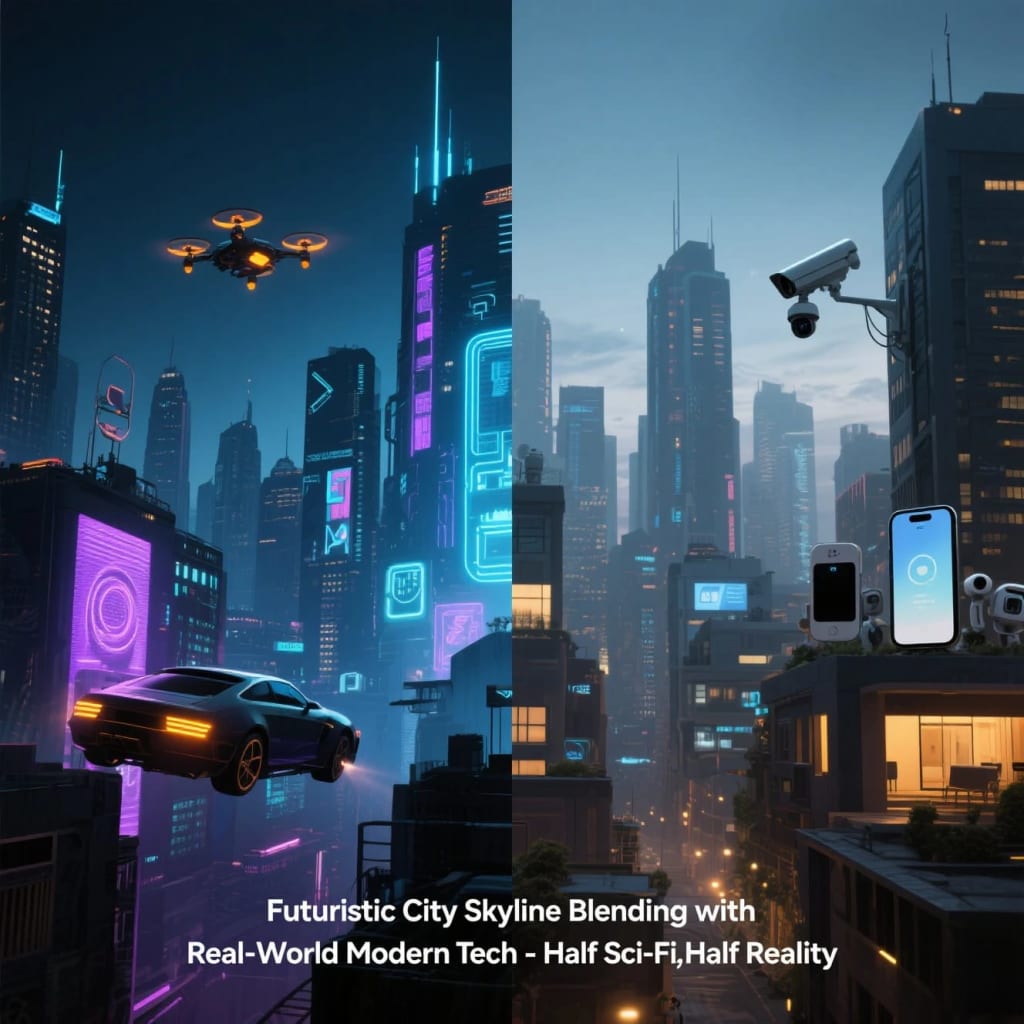

The Sci-Fi Movie That Predicted the World We’re Living In

it was supposed to be fiction. But decades later, its wildest ideas are now disturbingly real

It was a lazy Sunday afternoon when I stumbled upon the 1995 film VirtuWorld while scrolling through an old sci-fi movie collection. I’d never heard of it before. The VHS-like cover art was dated, the title font tacky, and the blurb on the back made it sound like another throwaway dystopian flick.

But I pressed play—and didn’t move for the next 112 minutes.

It wasn’t the acting that pulled me in. Nor the low-budget effects or the clunky dialogue. What shook me was the terrifying accuracy of its vision. Because VirtuWorld, a movie made three decades ago, didn’t just imagine the future. It predicted our present—with eerie precision.

The premise? A world where people no longer leave their homes. They live, work, date, and even travel through immersive virtual reality pods. The real world, ravaged by climate change and political unrest, becomes irrelevant. Human contact fades into a memory.

Sound familiar?

Back then, the movie seemed like pure fiction. In 1995, the internet was still young. Phones had cords. Virtual reality was a novelty in clunky arcade booths. Most people couldn’t imagine a future where human connection was filtered entirely through screens.

Yet here we are, almost 30 years later, and VirtuWorld feels less like fiction and more like prophecy.

Let me break it down.

In the movie, the lead character, Carter Vale, is a "Reality Architect"—someone who designs digital spaces where clients can live out alternate lives. He builds dream homes, fantasy vacations, and ideal workplaces. Today, we call them Metaverses. Platforms like Meta’s Horizon Worlds, VRChat, and others have turned that fantasy into reality. People now buy virtual land, attend concerts through headsets, and socialize with avatars.

Carter’s job was once entertainment. By the end of the movie, it becomes survival. That transition feels especially poignant after living through a global pandemic, when virtual spaces became the only way many of us could connect. Work-from-home culture is no longer a perk—it’s a norm. Entire jobs exist that are done without ever meeting a coworker in person.

But the movie goes deeper.

In VirtuWorld, people rely on AIs for everything—from personal assistants to therapists to partners. Carter’s best friend is an AI named Alma, who grows more self-aware and emotionally intelligent as the movie progresses. She gives him advice, comforts him, even challenges his beliefs.

Sound far-fetched? Then let me introduce you to ChatGPT, Replika, and the new wave of AI companions that millions talk to daily. They write our emails, help us brainstorm ideas, and in some cases, replace human relationships. Alma wasn’t a prediction. She was a blueprint.

What struck me most, though, wasn’t just the technology. It was the emotional fallout the film captured.

In the movie’s second act, Carter tries to reconnect with an old flame in the real world. Their awkward in-person meeting—after years of only talking in the digital realm—is painful to watch. They can’t look each other in the eye. They don’t know how to touch. The intimacy feels invasive.

That hit hard.

How many of us have felt more comfortable texting than talking? How often do we curate our lives online while struggling to feel real offline? The movie wasn’t warning us about technology itself—it was warning us about what we lose when we forget how to be human.

I went online to learn more about VirtuWorld. There’s hardly anything written about it. It flopped at the box office. Critics at the time called it “too bleak,” “too implausible,” and “too slow.” The director, one Anthony Kessler, never made another movie. In an old interview, he said, “I didn’t want to make a film about the future. I wanted to make one about where we’re heading if we don’t change course.”

Turns out, he didn’t need to make another movie. This one was enough.

We often look to classics like 1984 or Brave New World for dystopian warnings. But sometimes, the most haunting predictions come from forgotten corners. VirtuWorld wasn’t polished. It wasn’t perfect. But it saw us. It saw what loneliness and convenience and escapism could do when blended with unchecked tech.

And maybe the most unsettling part?

The movie ends with Carter unplugging. After a mental breakdown and a painful realization that his life is a simulation of comfort, not a reality of connection, he walks out of his pod and into the light. The camera pans out. The streets are empty. Buildings decaying. No one else joins him.

That final shot lingered in my mind long after the credits rolled.

We’re not there yet. But we’re close.

So maybe the lesson isn’t to fear technology. Maybe it’s to remember to live beyond it. To see that the future isn’t written in code or virtual blueprints. It’s written in the choices we make—to reach out, to connect, to be uncomfortable in the real world and still choose it anyway.

And maybe, just maybe, a forgotten sci-fi movie from 1995 was trying to tell us that all along

About the Creator

Muhammad Sabeel

I write not for silence, but for the echo—where mystery lingers, hearts awaken, and every story dares to leave a mark

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.