A Very English (Literary) Education

The 'Sleepless Nights' Series

There is no doubt that because of people like Shakespeare and Chaucer, writers such as the Bronte Sisters, Austen, Dickens, Shelley and Byron - it is safe to say that England has perhaps one of the greatest literary cultures in the world (but that doesn't take away from any other literary cultures, please don't hate me). But it has become clear that state schools in the UK in the current era are having a crisis of identity and faith around the subject itself.

TES (The Times Education Supplement) has recently released a report in which a very odd thing is investigated: why state schools in the UK mostly do the exact same books for GCSE. These books are/include: Macbeth by William Shakespeare, An Inspector Calls by JB Priestley and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by RL Stevenson or A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. I have my theories about why this is, but let's first try to clear this up for our friends across the Atlantic who perhaps, have no idea what I'm talking about:

The term 'GCSE' stands for 'general certificate of secondary education' in which at the age of 16, students across the UK in every walk of life take examinations in most subjects (especially the compulsory English, Maths and Science - and depending on the school, a modern foreign language - though that has been deleted from many of the compulsory subject lists in state school education that I have witnessed).

In order to 'pass' and complete education after you are 16 years' old (in what is usually referred to as sixth form, lasting from the ages of 16-18 years' old in which examinations will have results sent to your university of choice and you will receive a letter of whether you have got a place or not), you require to get a '4' out of a possible grade of '9' for English and Maths.

Note: It used to be the case in my day that you would get a lettered grade and must not only get higher than a 'C' in English and Maths but then higher than a 'B' in any subject you wanted to do afterwards (you would choose four).

The article in question is available here.

A Very English (Literary) Education

Leave Taking and Its Issues

The article first mentions the argument that many new books have been added to the GCSE syllabus such as a text entitled Leave Taking which seek to diversify an otherwise very English literary curriculum. As someone who is old enough to have remembered when American literature was on the curriculum, this is a strange idea I wanted to investigate. The main argument being made is that although these new and diverse books have been added en masse, schools aren't really taking them up for study. I can tell you objectively why and subjectively why.

Objectively, of course, it is relative to the amount of time an educator has on a particular topic and the ease of known and familiar resources to guarantee success in a subject where success needs to be achieved for the student to move on in life. Risk-taking is not in an educator's job description. Subjectively, the books that have been chosen are simply terrible. Leave Taking as a 'new and exciting' representation of immigrant literature is something else when The Lonely Londoners is right there and has been known to encourage humour and philosophical thought about the immigrant experience. I'm not going to lie to you, but it is a universally acknowledged fact that The Lonely Londoners is a legendary 20th century text even if we're not talking about the immigrant experience. Perhaps the only new book that has been added to the syllabus that is worth its salt is the fantastic novel, My Name is Leon by Kit De Waal.

Perhaps they've simply chosen the wrong books for representation thinking that more modern novels because of their more familiar use of language are therefore better. But something like Leave Taking being written in the Jamaican dialect of patois means that children who are not from that background (and in fact, some children who are) find it entirely inaccessible. Whereas, in a text like The Lonely Londoners, slang is used to a degree - but language can still be learnt in time for an examination with focuses on the diversity of identity.

Here's my point: half of the battle with English Literature is confidence. If you simply hand over a Shakespeare play to a child of GCSE age (14-16 years' old) and tell them to analyse it for themselves, unless they go to the kind of weird school I went to - chances are they're going to struggle and that's not good for a child who doesn't value literature already. However, if you hand them a Shakespeare play plus a DVD/Netflix adaptation of the play starring Denzel Washington, chances are it is going to be not only better understood, but in fact: enjoyed. The same goes for modern texts. Hand the child a book written in patois in the name of diversity and they are terrified - but hand a child a book they feel like they can read that showcases a similar level of diversity and they have a sense of achievement almost immediately. Half the battle is won.

Time, Expertise and Confidence

"Experts say many teachers lack the confidence to choose less popular texts, given the high-stakes nature of the subject, and that some schools cannot afford to buy new books."

I understand this argument. For example: if a school has been teaching An Inspector Calls for as long as time itself has existed, then they have not only accumulated tried and tested resources that ensure success at every level but also, they have probably got in their possession multiple copies of the book. In an age that has experienced funding cuts to education and lower grades in the subject of English Literature, it is less likely that an educator at whatever level will take risks with the funding or the marks the students will eventually get in the examination.

I expect at this point in the article there will perhaps be some empathy for the poor people who have to go through the hell of being told they have to teach entirely new material with no tried and tested methods. Yes, the TES article repeats the same ideas about this over and over again with scholarly representation but, I think it's important that it needs to be hammered home.

'Robert Eaglestone, lead on educational policy at The English Association and professor of contemporary literature and thought at Royal Holloway, University of London, said: “If you’ve got 30 copies of An Inspector Calls already, a lot of schools can’t afford to buy 30 or 60 copies of a new play or novel.”'

I've already stated the point about this above, but there seems to be a rising inclination to put more and more duties upon the people who educate your children whether that be a teacher in school, a mentor online or an extra-curricular volunteer. I think we are missing one group of people who have sole legal responsibility over what happens to the child: the parents. So, you cannot possibly blame educators for teaching the same texts over and over again. The resources are there, the methods are clear, the books are provided.

These people already have so much work to do - it literally never ends.

Professional Development?

To increase uptake of other texts, the Department for Education should provide free copies, as well as professional development, according to Mel Wells, a head of department for English at a school in Somerset.

It should also provide new schemes of learning with booklets and PowerPoint resources that could be a starting point for teaching a new text, she recommended.

Ms Wells said that in making the decision to teach An Inspector Calls she factored in the time it takes to prepare for a new text and create new resources, as well as concerns about not wanting to teach a text to a GCSE class before she has had time to refine teaching it.

This I don't agree with fully. I think that free copies should be provided but I don't think professional development will do anything. Instead, you should provide a clear framework of what exactly needs to be learnt and allow time for the teachers to come up with a way to teach that to an ever evolving set of students. Providing blanket professional development therefore, would render the whole thing completely useless and take up an unnecessary amount of the time teacher's have to possibly be doing other things.

It's easy to pass off the situation on to the Department for Education in the thought that they themselves also don't have anything better to do than talk about useless professional development to a bunch of people who would rather be actually doing the stuff than listening about doing it. Emails and Zoom exist for a reason. Use these tools to make the lives of teachers easier and more flexible.

That being said, not all professional development is bad. Some professional development considering the teaching of SEND students can be very useful. My question is: how much professional development can you physically provide without it becoming tedious for the educators involved? I think this constant band-aid of 'give some professional development towards x, y and z' is part and parcel of just throwing things at educators and expecting a little lesson of an hour or so of learning about random things per week should pretty much cover it. It's not realistic for someone who is constantly making decisions on the job.

A Combination of Issues and So Much More...

“The reasons for this could be due to familiarity, assumptions about examiner knowledge or preference, the time needed to acquire training and resources for other novels and plays, a lack of physical copies of the texts themselves, or a combination of these..."

This is what is quoted by being said by AQA in the article and I think it is both telling of how AQA both hits the nail on the head and misses the point. The first way (in which it hits the nail on the head) is that it states that it is a combination of issues and it is never really just one. AQA seems to be the only quotation here that has accounted for the fact that educators do more than one thing a day. The second way (in which I do not agree) is that they still put some of the concentration on training. Every single instance in which I try to investigate the training that is provided it is most of the time something that is getting in the way of actually doing the thing.

AQA has added three texts by women of colour for next year.

I'm going to say this: just because they are by women of colour, doesn't mean they are objectively good. Your random wattpad mate on Twitter is not Toni Morrison. They are not the same. I find that objective writing talent has been ignored in the face of wanting to please everyone ever. This is yet another issue - though AQA has identified the 'combination of these' issues, it hasn't identified perhaps one of the missteps it has made in choosing literature they believe is relatable but is not actually relatable.

Stating that you understand there's a problem and then adding more to the problem surprisingly, does not fix the problem.

May Contain Lies

Read the Lit in Colour research in full here.

Researchers for the Lit in Colour Pioneers pilot scheme found that teachers reported higher levels of engagement in the classroom when studying new texts added to Pearson’s specification.

Yeah, thanks a LOT Alex Edmans. But he has made me see every piece of literature with a strange and paranoid eye, especially this one. The research being referenced here is a bit dodgy to say the least and I'm about to break this into some sections for you to understand a bit clearer. Here's the issue that we encounter from the research done by Lit in Colour (and note: this is an organisation I really respect, I'm quite shocked about their purposeful want to misdirect research)...

Teachers responding to the survey were largely positive about changes in the range of set texts that are now available for study, but a substantial number of them warned that the canon was ‘still largely white male and dead’, and that there was still not sufficient racial diversity in the options available.

The key phrase I think we are looking at here is "teachers responding to the survey" which will be only the teachers who are involved with the ideas Lit in Colour put forward. It's a strangely worded phrase which basically means 'the people who responded to our survey were people who generally agree with us'. Against the fact that the very curriculum reports themselves are stating that not a lot of schools are actually studying these texts leaves us with the thought that even though the people responding to the survey generally agree that making the curriculum more diverse is a good thing, they don't actually teach those texts in reality.

Yes, Lit in Colour acknowledges this in the research to a certain degree, but doesn't say anything about the wording of their reporting - which has no real data set that can be corroborated. In fact, they could have made the whole thing up for all we know.

There are a few more concerning wordings that we need to look out for. These of course, may contain lies. These include:

1) "Teachers and students report higher levels of classroom engagement when studying Lit in Colour Pioneers texts..."

2) Students in the matched dataset were less likely to report...

3) "But others referenced the idea that canon literature made them feel that English was not for them:

‘Shakespeare makes you feel small.’

Whereas studying their Lit in Colour Pioneers text made them feel ‘smart’."

4) "One teacher reported [insert shoddy phrasing here that seems to support everything Lit in Colour has ever said, ever]"

5) The fact that the tables often say 'excluding missing data' - because why would you miss data if you're collecting survey responses, really?

This is just the beginning of poking holes in the Lit in Colour report. That does not necessarily mean that diversity in English Literature is a bad thing, perhaps it is a good thing and presents a net-positive to confidence in the subject. However, we can also be choosy about that literature, purposefully selecting things that are just as in-depth and explorative about experience as their native counterparts. But that is not really what is happening, is it?

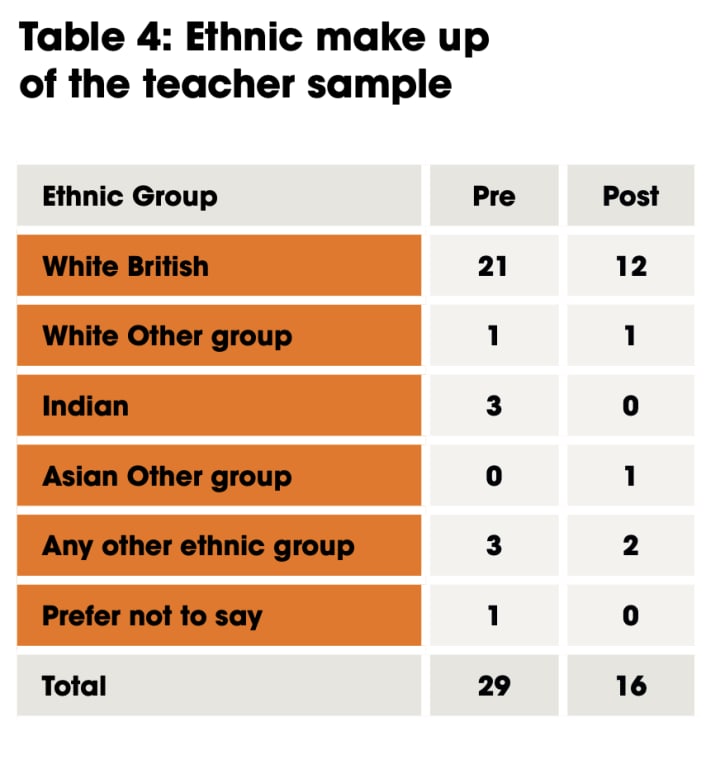

I think what is the most telling is the teacher samples from the references of who participated in the survey because not only does it not add up, but they seem to willingly admit that the majority of opinions are made up from White, virtue-signalling teachers rather than the teachers of which these cultures represent.

On top of this issue however, there are many references in the research to 'one teacher reported'. The question here is if only 16 teachers reported on anything by the end of the survey then that really is not representative of anyone is it? No, it is not.

The last thing I have to say is upon the 'limitations' section in which they admit there is a smaller sample size than they would have liked, but of course this is flipped so that we understand it is still representative. Imagine a disease charity doing this by saying 'hey we have a small sample size that have said the disease isn't really all that bad, so I think that's a good start to say the disease isn't that bad at all'. Well, any sane person would question that:

"Nonetheless, despite the limited data we are able to show some impacts, and therefore to start to show important relationships between teaching texts by authors of colour and certain outcomes."

The phrase 'start to show' doesn't make us any more confident about the way they are conducting research. Just because they call it 'pilot research' doesn't make it any better. I could get a bigger sample size if I did the research. It simply isn't reflected by the reports done by the actual examination boards in which the worries of the majority of educators and education research teams have been highlighted.

So let's have a look at a University of Oxford professor and what she had to say about the research:

“When you give schools and teachers the support they need, it has a huge impact on engagement with English literature. People want to teach these texts and they want the resources to do it. [paragraph break] The last couple of years there have been lots of good study guides coming out for these new texts, and that will really support this change. It is very tempting to stick with what you know you can get good grades in. But the research shows you can do just as well with the new texts, if not better.”

A tone-deaf response to struggling educators clearly struggling with the amount and the freshness of material when there are practically no past papers to go off as they update the curriculum, let's take a look at what kind of thing she researches then: "...associate professor of English and literacy education at the University of Oxford and one of the authors of the Lit in Colour report." Oh. Okay. That actually explains a lot.

Choosing Texts

Last year 76 per cent of AQA candidates opted for Macbeth, along with 70 per cent of those taking Pearson Edexcel and 52.2 per cent of those taking OCR. The next most popular play for all three exam boards was Romeo and Juliet.

There's a reason for this: it's because these two plays are perhaps the two that are most adapted out of all the Shakespeare plays not only in the theatre, but also in the cinema, also on Netflix, also in cartoons and other media. When you've got a very recent adaptation of Macbeth containing Denzel Washington alongside a very sub-par (in my humble opinion) but fun adaptation of Romeo and Juliet starring Leonardo DiCaprio, two stars very recognisable to the young folk, then why would you bother with the third most (but in my opinion far more superior) play of The Merchant of Venice? Not many of the children recognise Al Pacino, no matter how legendary his performance was. We cannot ignore that this perhaps has something to do with it.

Another thing that has something to do with it is that both Romeo and Juliet and Macbeth are tragedies which contain a horrific level of violence and death, which definitely appeals more to young boys than the friendship, love and racial elements that dominate the critical thought we go through when reading The Merchant of Venice perhaps does. And if one of the arguments a lot of the arts and humanities is primarily concerned with is how to appeal to young boys, then this is how you appeal to them. I would say that the process here, needs to be trusted for those who have a majority male intake, which is especially true for inner-city schools.

This is also the same sort of argument that comes out of not many schools taking up Jane Eyre. Now, I read Jane Eyre when I was in school. It wasn't my GCSE text, but it was sometime during the school era. But here's the thing: I went to an all girls' school, we enjoy Jane Eyre. When you are teaching in a majority boy school or even a mixed school in which it is especially difficult to get boys involved in literature, perhaps Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is the way to go. I'm not saying girls can't read that too - but please understand that educators are trying to make the best decisions they can for the best results possible in a limited amount of time with a fairly challenging focus group. Making their job that tiny bit easier could be a better idea than pointing the misdirected finger.

As for A Christmas Carol well, we go back to not only the adaptation argument but we make a new argument: many children already know the basis of the story. If you have a very challenging group of students who struggle to read at a basic level, A Christmas Carol is a great way at providing confidence whilst also teaching the children how to read and gain confidence in reading 19th century literature. We can't simply look at 'oh it's written by a dead white male, so it must not be as good as another book written by someone from another country' as a measure. We do need diversity on the syllabus, but we need it to be mindfully researched to focus on the optimisation of confidence and ability in the majority of students who are struggling with the subject. This comes down to boys who are from low-income families. Books like Leave Taking simply don't support that.

Conclusion

This is in fact the main problem:

"...many schools report pupils having a reading age significantly below chronological age."

This can only be solved through rote learning if they are secondary age. Reading needs to be something involved with at an early years stage for the best possible results and therefore, it is another complaint from a section of education which receives the problem instead of creates it. But, the secondary education system is the one that normally gets blamed for the 11-year-old (the age of a secondary student at the start of this education) not having the reading age of an 11-year-old when we often forget they have had a number of years of education before this that are meant to explicitly teach reading.

So of course, I'm back to my old argument. The newer generations are becoming less and less literate as the years go by. Now I turn to you: how do we solve this problem?

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 280K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.