THE REAL-LIFE MYSTERY BEHIND EDGAR ALLAN POE'S "THE BLACK CAT"

fiction in Poe’s classic story of a murderer.

The bones were discovered by George Stebbins while he was tearing down a stone wall in the cellar of his house in Northfield, Massachusetts. The bones of the head, spine, arms, and legs all emerged first. The fact that the remains were crammed into a space less than three feet square suggests that the body had either been dismembered or had decomposed to a skeleton before being buried. Had Stebbins, who ran a ferry service on the Connecticut River close to the state's border with Vermont and New Hampshire, disturbed an unmarked grave? Or did the discovery have a more sinister justification?

He told the Vermont Phoenix that "the condition of the wall appeared as if part of the wall had been removed, the human body crowded in, and the wall, unworkmanlike, replaced." In his letter to the local Brattleboro newspaper, which was published after press reports of the discovery went public in the summer of 1842, he emphasised the word "unworkmanlike." He made it clear that he thought the body had been buried behind the wall by someone who was either inexperienced in building stone walls or had been pressed for time.

The news was first reported in mid-July by The Greenfield Democrat, a nearby town's newspaper. The bones were described as being "in a good degree of preservation" and must have been buried behind the wall within the previous 25 years, which is when the house was built, before Stebbins moved in, and just before he started expanding the cellar, according to the article titled "Mysterious." The bones were identified as those of a woman who had died between the ages of sixteen and twenty by doctors called to the scene. Additionally, there was proof of wrongdoing.

According to what the Democrat reported to its readers, "there is a hole on the back part of the skull about the size of an ordinary sized bullet, and, judging from appearance, the probability is that she came to her death by being shot." The victim and her killer's potential identities were eagerly offered by the newspaper. About 20 years prior, a young woman with the last name Kendall vanished in the Northfield area; her body was never discovered, and it was assumed that she had drowned in the river. However, there were rumours that "an unprincipled and vicious man by the name of Mallory," who later served time in the Vermont state prison, was the culprit at the time.

The newspaper hoped that the murderer might be identified at this late hour. Though it may take time, justice will eventually catch up to the wicked. Let men gain knowledge from Providence's decrees. Newspaper editors in distant towns and cities were drawn in by the details of Stebbins' discovery of a potential murder victim. A number of newspapers, including the Boston Post, Charleston Daily Courier, and Pennsylvania's Sunbury Gazette, published the entire or a portion of the story. It was also republished as far away as Holly Spring, Mississippi.

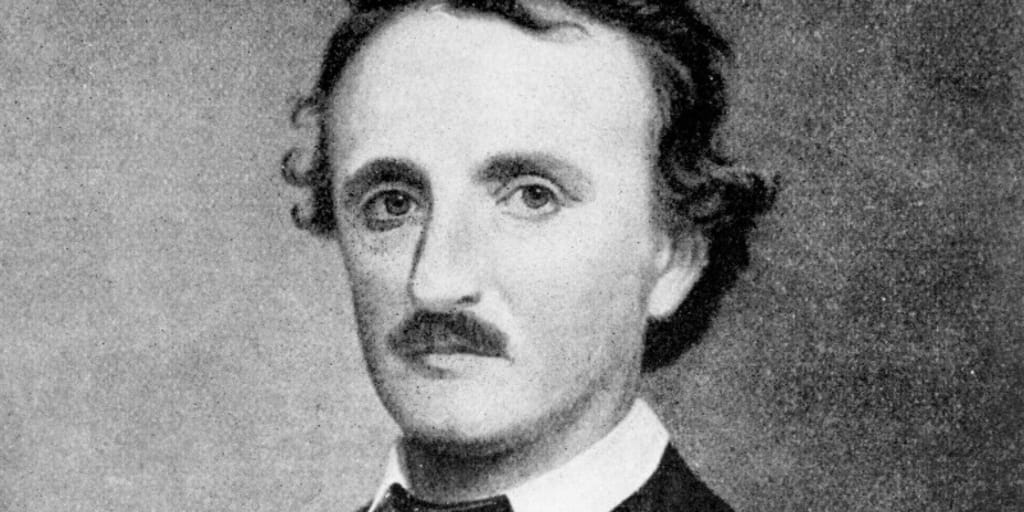

The Greenfield Democrat's report was reproduced verbatim on the front page of the Saturday, July 16, edition of the Public Ledger in Philadelphia, making it unlikely that readers would have missed it. A writer whose name frequently appeared in the Public Ledger and had lived in Philadelphia for four years would have recognised the tale immediately. His interest in the macabre would have been piqued by the grisly discovery of the bones, the suspicions of a heinous murder, and the devious attempt to hide the victims' remains and the proof of the crime.

However, Edgar Allan Poe would require something in order to turn the news report into a gothic horror story that explored the depths of sin and depravity. A cat. cat in black. A little over a year after George Stebbins discovered the bones, "The Black Cat" made its debut in the Saturday Evening Post in August 1843. Similar to "The Tell-Tale Heart," which was released in January of the previous year, it is presented as a murderer's admission of guilt. The unnamed narrator of "The Black Cat" describes how drinking too much turned him from a person "noted for the docility and humanity of my disposition" into a violent abuser filled with "the fury of a demon" on the eve of his execution.

He acknowledges hitting his wife with "personal violence" and torturing and killing his black cat Pluto by chopping off one of its eyes. The narrator finds and adopts another one-eyed black cat despite being tormented by guilt but unable to rein in his drinking and destructive behaviour. However, his new pet makes him think of the harm he had done to Pluto, and he soon develops a dislike for it. He nearly trips over the cat as he enters his cellar with his wife on an errand, setting off an explosive fit. To kill the cat, he grabs an axe, but his wife stops him. He admits that the interference caused him to become "more than demonically enraged," at which point he "buried the axe in her brain.

" He cuts a hole in the cellar wall, places her body inside, and closes the hole to hide the crime. He notices the cat is missing after meticulously replacing and re-mortaring the stones "so that no eye could detect anything suspicious." Unaware that the woman's remains are just a few inches away, the police look into the woman's disappearance and even search the cellar. The narrator remarks on the cellar walls' sturdy construction and taps the stones obscuring the corpse in what he calls a "frenzy of bravado." A murmured noise coming from inside the wall becomes a "inhuman... wailing shriek." The body of his wife is discovered after the officers tear down a wall.

The black cat is perched on her head, surrounded by the remains and the source of the shrieking. Poe's "The Black Cat" is regarded as a classic. Could it have been inspired by a true story? The introduction to the story when it first appeared in The Saturday Evening Post gave a hint that it was, saying that it combined "probable events with improbable circumstances, so blended with the real that all seems plausible." At the time, reviews were either positive or negative. While London's Literary Gazette dismissed it as "impossible and revolting," the United States Gazette praised it as "a thrilling original tale." The story, in Blackwood's Magazine's opinion, was nothing more than a "wild and horrible invention." Hervey Allen, a Poe biographer, concurred in the 1930s, stating that "The Black Cat" was "the mad realisation of a dream.

" The Northfield discovery appears to have been the first to be mentioned as a potential source of inspiration for "The Black Cat" by Poe scholar John E. Reilly. Reilly, an English professor at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, and one of the organization's founding members, wrote an article linking the case to the tale that was published in the journal Nineteenth-Century Literature in 1993. Of course, there are noticeable differences. There was no indication that a man had killed his wife in the Northfield case, which appeared to be a shooting, and the police were not present when the bones were discovered.

There wasn't even a black cat; Poe's narrator referred to them as "witches in disguise." In spite of the differences, Reilly maintained that "the nucleus of Poe's episode and the nucleus of the news item are identical: the body of a woman who died by a puncture of the skull is discovered immured in a basement." Reilly gathered some strong circumstantial evidence to back up his assertion. A 1840 article in the Philadelphia Public Ledger praised Poe's "extraordinary powers" and "originality of genius," and Poe was probably a subscriber or frequent reader, making sure he did not miss such kind words.

And just months before he wrote "The Black Cat," the Public Ledger reported on the bones' discovery. Poe had read the story's manuscript to Felix Darley, an illustrator he collaborated with, in the fall of 1842, though it wasn't published until the summer of 1843. And it wouldn't have been the first time Poe had based one of his gruesome stories on news accounts of a horrifying crime. The sensational murder of a young woman named Mary Rogers in New York City in 1841 is his most notorious example of turning fact into fiction.

She was given the new name Marie Roget, the setting was changed to Paris, and Poe assigned his detective C. Auguste Dupin to the case, but the plot was, in his words, "a series of nearly exact coincidences," mirroring the actual crime. The identity of the woman who was interred in ferryman George Stebbins' cellar, as well as her cause of death, are still unknown. A group of Northfield locals wrote to the Gazette in Bennington, Vermont in September 1842, swearing that no woman named Kendall had ever lived in the town, much less vanished without a trace two decades earlier. Furthermore, they argued that Mallory, the man accused of killing her, would have been no older than twelve years old at the time.

The editor of The Gazette reprimanded the Greenfield Democrat for insinuating that Mallory had committed "so horrid a crime" without providing any evidence, and he urged the newspaper to "clear Mr. M. from these unjust suspicions." Another explanation for the discovery was provided by other Northfield locals. One insisted that Stebbins' home was constructed on the site of a nearby fort that was built more than a century earlier, during frontier conflicts with local tribes. A Mr. Tiffany, who asserted he had been present when the cellar was initially dug, claimed that "human bones have frequently been dug and ploughed up here.

He claimed that bones found during construction had been collected and thrown behind the wall, where Stebbins had discovered them. No inquiry appears to have been opened to ascertain the age of the bones or search for criminal activity. A coroner's jury should be appointed, according to a letter to the editor that was published soon after the discovery in the Gazette and Courier, another newspaper in Greenfield. "There had been in former years a continued and very offensive smell," the author, who wrote under the alias "Anti Cryptamia," claimed of Stebbins' cellar. However, no mention of an inquest or other official action was found when searching through the remaining copies of local newspapers published in the area.

The Greenfield Democrat was mistaken in thinking that justice would ultimately triumph over the evil if the bones belonged to a murder victim. Additionally, there is no sign of the "unprincipled and vicious" Mallory, who may have been the John Mallory detained in 1846 along with other members of a "den of counterfeiters" close to the Massachusetts-New York border. Unlike Poe's tortured and unlucky narrator, did a murderer in the New England town of Northfield get away with murder? Possibly. Was a news story about the discovery of bones behind a cellar wall the source of Poe's inspiration for "The Black Cat"? Decide for yourself. (“The Strange Real-Life Mystery Behind Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Black Cat’”)

About the Creator

Elle

I love to write and share my stories with others! Writing is what gives me peace.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.