Cato vs Caesar: The False Dilemma of Modern Democracy

From Ancient Rome to Today’s Politics: Elites, Demagogues, and the Search for a Democratic Alternative.

I write this article against the backdrop of today’s political turbulence, the rise of polarisation and extremism in the United States, where hate speech and even political assassination are no longer unthinkable. These events follow an already toxic atmosphere in Europe, with authoritarian tendencies, corruption, and populist rhetoric undermining democratic institutions. In this climate, the dilemmas faced by Rome on the eve of Caesar’s rise feel less like distant history and more like an urgent mirror for our own time.

Praelocutio – Introduction

There are moments in history when the fate of a society, a country, a regime or in our case, a republic, seems to hang on a fragile thread. The late Roman Republic was one such moment. On one side of the political spectrum stood Cato the Younger, austere, uncompromising, a defender of tradition and the senatorial elite. On the other, Julius Caesar, whose dazzling charisma and promises to the people masked his alliances with the wealthiest oligarchs of his age, Pompey and Crassus. Few rivalries in history capture the contradictions of politics as vividly as the clash between Cato the Younger and Julius Caesar. Their conflict was not only personal but emblematic of a deeper crisis in the late Roman Republic between the stern guardianship of tradition and the seductive promise of popular reform. Revealing the deeper fault lines of a society caught between an elitist institutionalism and a populism bankrolled by oligarchs. It is an old duel, one that did not end with the fall of the Roman Republic but still echoes in the dilemmas of our modern democracies.

Today, as someone who has lived my whole life, I have often found myself faced with the choice between technocratic guardians of institutions, distant and aristocratic in their outlook, or populist demagogues who claim to speak for “the people” while standing shoulder to shoulder with billionaires and vested interests. This is the purpose of my article: to show that the false dilemma of Cato and Caesar has not disappeared; it has only changed its names.

Primordium - Sources

Ancient writers and Modern intellectuals never ceased to return to these figures. Plutarch, in his Lives, presents Cato as the embodiment of Stoic virtue, a man whose very life became a moral argument for the integrity of the Republic. Cicero, while admiring Cato’s integrity, also notes his inability to bend in moments of necessity. Caesar, by contrast, appears in the pages of Plutarch and Suetonius as dazzling and charismatic, capable of inspiring both admiration and fear. To Cicero, he was at once a brilliant statesman and a dangerous subverter of republican norms.

Modern intellectuals, too, have read this rivalry as more than a story of antiquity. Antonio Gramsci wrote of “Caesarism” as the moment when political paralysis creates space for a charismatic leader to resolve crises, often by concentrating power. While Max Weber, in his typology of authority, analysed charisma as a disruptive yet compelling force, forever in tension with bureaucratic stability. More recently, theorists of populism such as Chantal Mouffe and Cas Mudde have debated how political movements invoke “the people” to construct legitimacy. For me, the duel between Cato and Caesar thus becomes more than an episode in Roman history: it becomes a mirror for democracy itself.

Roma in speculo - Rome as a Mirror

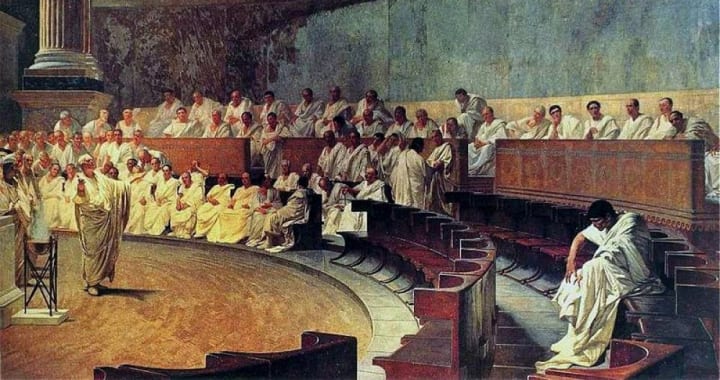

To understand this false dilemma, we must first return to the Roman stage.

The Optimates, embodied by Cato, represented the entrenched power of the Senate. They defended the old order with a mixture of moral severity and political elitism. To simplify it, they defended an elitist institutionalism in which the Republic was governed by the few under the guise of tradition. Cato himself, even though was praised by scholars for his incorruptible character, lived in personal austerity but believed firmly that only the senatorial class was fit to govern.

The Populares, represented by Caesar, claimed to champion the plebs, the common citizens. Yet Caesar’s “populism” was far from simple. His ascent was paved not only by his own aristocratic background but also by the money of Crassus, the richest man in Rome, and the legions of Pompey, the great general. Behind the façade of defending the people stood oligarchic power, military might, and political violence. Cicero himself, both fascinated and horrified, wrote of Caesar’s brilliance while fearing his dismantling of the Republic.

In this struggle, neither side offered a true democratic alternative. The Optimates defended an elitist republic that excluded most Romans from genuine participation. The Populares invoked the people while forging alliances with the wealthy few. The supposed choice was between oligarchic tradition and oligarchic populism.

The False Dilemma Today and the American Case

Here lies our timeless dilemma. Modern democracies often seem trapped between institutional elites and populist leaders. The figures have changed, but the logic endures. Like the Romans of the late Republic, we are asked to choose between Cato and Caesar, between an aristocracy of rules and a demagogy of charisma.

But I want to change this question and doubt this dilemma. My question: Why must democracy always oscillate between these two poles?

The American Case

I am starting with the United States because this false dilemma has become almost archetypal there. The Republican populism of recent years speaks the language of the working class, promising to protect jobs, revive industries, and defend national dignity. Yet its legislative record often tells another story: attacks on labour rights, attempts to weaken social security, hostility to universal healthcare and public education. A party that speaks like Caesar but acts like Crassus.

The so-called liberal establishment, meanwhile, protects the institutional framework of democracy. It defends courts, procedures, and the rule of law. Yet it too has overseen widening inequality, financial deregulation, and policies that protect the wealthy. Like the Optimates, it holds to the letter of the republic, but often forgets the spirit.

The result is a political duopoly not unlike that of the Optimates and Populares: one side cloaked in elitist legality, the other in populist rhetoric, both unwilling to transform the underlying structures of inequality.

The European Case

The European Union also offers its own version of the Roman drama. On one side, the institutions in Brussels, particularly the European Commission and the European Central Bank, often embody the spirit of the optimates, defenders of institutional continuity, fiscal discipline, and an entrenched technocratic order. Their doctrine of austerity and “fiscal solidity” in the aftermath of the Eurozone crisis has repeatedly forced member states, especially in Southern Europe, into policies that prioritised market stability over social welfare, much like the senatorial elite of Rome defended their privileges at the expense of the plebeians.

On the other side, the rise of authoritarian-populist leaders, with Orbán in Hungary being the most notorious. Additionally, with examples such as Meloni in Italy, Le Pen in France, or the far-right movements in Poland, present a populares-style challenge to liberal Europe, claiming to speak for “the people” while in practice aligning with oligarchic business interests and undermining democratic freedoms. The EU thus finds itself trapped in the same false dilemma Rome faced: a sterile choice between rigid elitism and corrosive populism, where neither side can construct a genuinely democratic and socially just alternative.

Aliud – Another choice

If both the technocratic elitism and the authoritarian populism of Europe’s and America’s examples amount to an unequal and problematic situation in society, then the question becomes urgent: Is there an alternative and if so, what would it look like?

Historically, moments of political crisis have allowed progressive forces to articulate a third path, one rooted not in the preservation of privilege nor in the exploitation of resentment, but in the construction of genuine democracy. In the European case, this means moving beyond the sterile debate between austerity and demagoguery and instead reclaiming the politics of social rights: free education, accessible healthcare, strong labour protections, and environmental justice. Such an agenda does not fit comfortably within either camp, because it undermines both the neoliberal order of the optimates and the oligarchic alliances of the populares. Yet it is precisely this refusal to be captured by false choices that makes a progressive alternative credible. The challenge is not only institutional, but also cultural: to rekindle the civic imagination of democracy as a living practice, not a managerial system, and to reassert that Europe’s future must be measured not by its fiscal surpluses but by its ability to safeguard dignity and equality for all its citizens.

What might such a path look like?

I believe that such a path should begin with social rights: the defence and expansion of labour protections, universal public healthcare, free education, and social security. Without these, democracy becomes a form without substance. There are also the required institutional reforms that weaken the grip of oligarchic wealth: campaign finance restrictions, transparency in lobbying, and the empowerment of citizens’ assemblies and participatory budgeting. In our modern democratic societies, there is also a need for cultural transformation, where civic education would teach not only rights but responsibilities, a public sphere that values dialogue over demagoguery, and political organisations that build collective leadership rather than cults of personality.

Such a project recalls not the Roman Republic but the Athenian experiment with direct democracy, where institutions were porous to popular participation. It would not imitate Athens, but it would share its conviction that democracy must be more than the choice between two ruling factions.

Where is the Left?

Many imagine political the Left embodying a third path. Thinking that the Left should not align with the institutional elitists, defending rules without social justice or ride the wave of populist demagoguery, risking capture by oligarchs and personality cults. Knowing, of course, the history of the 20th-century Soviet style Left, which notoriously created some of the most gruesome personality cults, that would require a whole other article just to be briefly mentioned.

Interestingly, Chantal Mouffe has argued for a left populism, as a way to reclaim the language of “the people” without abandoning democratic institutions. In her view, politics is not about erasing conflict but about channelling it into agonistic, democratic forms. To speak for “the people” must not mean following a Caesar but building a demos. The Left must therefore resist the temptation to become either a Cato, noble but detached or a Caesar, popular but dangerous and opportunistic. Its role is to insist on democracy not only as a set of institutions, but as a living practice of equality.

Yet, I believe that for this vision to matter, the Left must also resist its own worst habits: the drift into intellectual elitism, self-referential theory, or insular organisations that substitute internal hierarchies and nepotism for genuine collective action. A movement that aspires to democratize society cannot mirror the closed circles of power it seeks to challenge. Instead, it must cultivate openness, participation, and realism. The task is not to construct a perfect ideological fortress but to create a political practice that empowers ordinary citizens to shape their future. Only then can the Left distinguish itself from both the rigid elitism of the optimates and the demagogic theatrics of the populares.

Clausula – Conclusion

In the end, I should mention that the struggle between Cato and Caesar ended with Caesar’s triumph and the death of the Republic. Creating a linear history of a few charismatic dictators and a lot narcissistic dangerous one that eventually after centuries of existence brought along the way a great deal of disaster, suffering creating an empire that also played an important role in innovation, science and arts since it complete fall in the West with the non-stop Visigoth invasions when finally in 476 AD when the last emperor, Romulus Augustulus was deposed by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer. Whereas in the East, it continued for nearly another thousand years, till the fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD by the Ottomans.

I should end this article with a nice cliché and mention that history is not destiny. Our democracies today face their own Caesars and Catos. We are told to choose between institutional elites who defend rules without justice and populist leaders who promise justice while dismantling rules. This is the false dilemma of modern democracy. The challenge for all who believe in democracy as more than a formality is to break this binary. To reject both oligarchic elitism and oligarchic populism. To create instead a politics that unites equality with participation, justice with institutions.

Written and published by Sergios Saropoulos

About the Creator

Sergios Saropoulos

As a Philosopher, Writer, Journalist and Educator. I bring a unique perspective to my writing, exploring how philosophical ideas intersect with cultural and social narratives, deepening our understanding of today's world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.