Cultural Protestantism and The Spirit of Austerity

The Moral Logic of Capitalism. How Protestant Ethics Have Shaped Financial Reality

It was a relatively warm night in Berlin when this article began to take shape. I was sitting in a pub in Charlottenburg, half-listening to the hum of overlapping conversations across from me, two friends were describing the economic differences between East and West Germany, and how culture still seemed to influence wealth, ambition, and social discipline. Something about it struck a nerve. This article is a reflection on that influence, on how a religious ethos may have evolved into an economic morality, shaping not just policies but entire cultures.

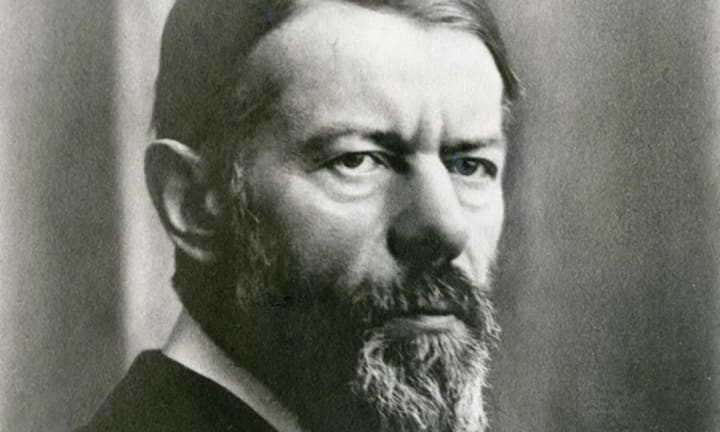

Max Weber

Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism remains one of the most intriguing attempts to link theology with economic behavior. The German sociologist and economist argued that after the Protestant Reformation, Calvinism introduced a new attitude towards work and wealth, one that would profoundly shape the modern capitalist ethos. Calvinists, according to Weber, were haunted by the doctrine of predestination, the belief that only a select few were destined for salvation. With no clear way of knowing if they were among the chosen, Calvinists sought reassurance in worldly success. They built businesses, generated wealth, yet lived thriftily, reinvesting surplus rather than indulging in luxury. In doing so, they unintentionally laid the groundwork for a self-sustaining capitalist system.

Economics as a form of Self-punishment

Weber did not view capitalism merely as an economic activity, but as a cultural and psychological necessity, one that incorporated a sense of sin. The Calvinist work ethic was not simply a practical reaction to material conditions, but a psychological necessity rooted in fear and hope. Predispositional faith created anxieties, and this anxiety became the catalyst for the desire for productivity. Thus, work transformed into a spiritual quest. In the modern world, this necessity for productivity and austerity continues to exist, with work becoming a form of spiritual "search" or even "salvation." Indeed, it is a perception often found in the lower, primarily economic, strata, something I can confirm through my own personal experiences. In our society, everyone is defined by their work: "I am a doctor," "I am a lawyer," "I am a teacher." How many times have we heard such conversations without ever discussing who we really are as people beyond our professional identity?

"The poor deserve to be poor"

Weber wrote that “the waste of time is thus the first and in principle the deadliest of sins,” because human life is short and every moment must be used to assure oneself of salvation. Laziness and sloth were mortal failings, but so too was the spontaneous enjoyment of life. In the modern context, this ethic morphs into a problematic psychological form of self-punishment. It does not bring redemption or financial responsibility, but instead promotes inequality. It conceals the corrupt features of capitalism: economic nepotism, the concentration of capital among the elite, the divestment from the arts and sciences. Perhaps the most alarming aspect is that it fuels a propagandistic narrative that the poor deserve to be poor, that they have failed economically and morally because they did not adhere to fiscal discipline. This morality, however, has transformed into an economic tradition that dictates the poor deserve their poverty. And when this morality is combined with capitalism, a deep inequality is created. The poor, though often victims of systemic issues, are characterized as responsible for their own misfortune. This, beyond being absurd, can be seen as deliberately ignorant in order to promote an ideology that justifies and blesses both social and geopolitical inequality.

The 2008 Reformation: Austerity

My reference to geopolitical inequality leads me to the period after 2008, when austerity became not merely an economic policy but a form of moral theater or even a religious sect, as a way of extending the once religious, but now political and social, Protestantism. In countries like Greece, Spain, and Ireland, the debt crisis was framed as the consequence of collective indulgence, with austerity posed as righteous penance. The idea of debt as sin and austerity as redemption shaped not only public discourse but also EU policy. Normally, high unemployment in a country would be counteracted by printing more money, thereby weakening the currency, boosting exports, and attracting tourists and investors. But within the Eurozone, monetary policy was shared, and the needs of nations like Greece (with 25% unemployment) clashed with those of Germany (with under 5%).

The euro was a political project, not an economic one. Unlike the U.S., where poor states receive continual transfers from richer ones, the EU lacked mechanisms for real fiscal solidarity. So austerity became the only dish on the menu. But austerity measures, which mostly involved cutting public spending, disproportionately hurt the most vulnerable. While framed as "common sense" or "fiscal responsibility," austerity confused virtue with vice. It punished the poor for systemic failures while the wealthy remained insulated. This is where the moral logic becomes dangerous. Policies rooted in supposedly neutral economics were, in fact, profoundly ideological. Austerity masked class politics behind a veil of virtue. It harmed more than it healed, and in doing so, deepened the very inequalities it claimed to fix.

Cultural Protestantism and Austerity

Cultural Protestantism also had a quiet but powerful influence on how different countries perceived austerity. Protestant-majority nations like Germany, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia brought with them a moral culture that valorized thrift, personal responsibility, and financial prudence. These values shaped the political stance of creditor nations, reinforcing the belief that debtor countries were morally lax and in need of discipline. In contrast, Catholic and Orthodox countries like Spain, Italy, and Greece often emphasized communal welfare, social solidarity, and the state's responsibility to protect its citizens. This divergence in values wasn’t just theological; it was political. It affected how policies were debated, justified, and resisted. Where Protestants saw austerity as a necessary correction, Catholics and Orthodox populations often saw it as unjust punishment. The otherwise united Europe, then, transformed into a battleground of politics and ethics for survival.

Waiting for the next Reformation

Finally, we must look at the broader cultural implications: neoliberalism and its Protestant roots. Neoliberal ideology often treats economic failure as a personal failure. If you're poor, it's because you didn't work hard enough; if you're rich, it's because you deserved it. This echoes the old Protestant idea of individual responsibility before God, now secularised into economic doctrine. It reinforces meritocracy, but only as a myth. The poor are labeled undeserving; the rich, virtuous. Structural injustice disappears behind a moral smokescreen. In this way, capitalism perpetuates itself not only through markets but through meaning. It tells a story where suffering is earned, and success is proof of moral worth. And perhaps that is the most enduring legacy of all that I mentioned in this article.

Written and Published by Sergios Saropoulos

References

• Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. 1905. Translated by Talcott Parsons. Routledge, 2002.

• Beckford, James A. "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism: A Reconsideration." Sociology of Religion, vol. 62, no. 3, 2001, pp. 259–276.

• Sombart, Werner. The Quintessence of Capitalism: A Study of the Relationship Between Calvinism and Economic Development. Translated by M. R. Black, 1915.

• Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer, Harvard University Press, 2014.

• Brown, Wendy. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism's Stealth Revolution. Zone Books, 2015.

• The Guardian. "Greece Austerity Protests – In Pictures." The Guardian, 13 Feb. 2012, theguardian.com/world/gallery/2012/feb/13/greece-austerity-protests-eurozone-bailout.

• The Economist. "The Eurozone's Debt Crisis Explained." The Economist, 22 Nov. 2011, economist.com/news/europe/21537911-how-eurozone-debt-crisis-was-created.

• Klein, Naomi. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Metropolitan Books, 2007.

• Wright, Erik Olin. Class Counts: Comparative Studies in Class Analysis. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

About the Creator

Sergios Saropoulos

As a Philosopher, Writer, Journalist and Educator. I bring a unique perspective to my writing, exploring how philosophical ideas intersect with cultural and social narratives, deepening our understanding of today's world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.