The Penguin Who Walked Into the Void

Why the most haunting scene in documentary history is actually a story about you, me, and the courage to leave the huddle.

Part I: The Huddle

There is a story about a penguin.

It sounds like a joke, the setup to a punchline you’d hear at a bad open mic night. But it isn’t a joke. It is one of the most haunting things ever captured on film.

The setting is the bottom of the world. Antarctica. McMurdo Sound. A place where the wind doesn’t just blow; it screams. It is a landscape of violent white, where the horizon is a myth because the sky and the ice are the same blinding shade of nothingness.

Here, survival is a numbers game. It is an act of collective submission.

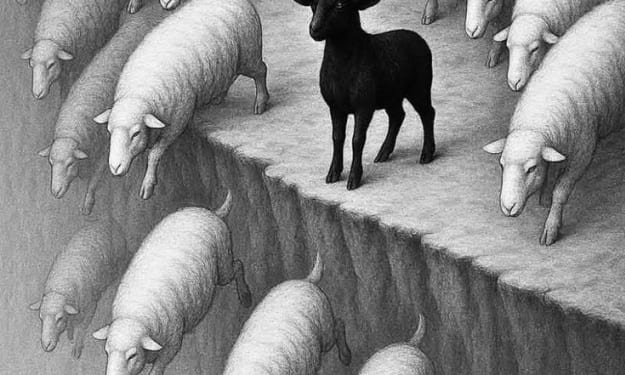

Thousands of them stand together on the ice. The colony. A shifting, shuffling organism made of black and white feathers. They are huddled. They are safe. They are freezing, but they are alive.

If you have ever seen a penguin colony up close, or even in high-definition video, you know it is not the dignified gathering we imagine. It is loud. It smells of digested krill and guano. It is a constant, frantic jostling for position. The birds on the outside of the circle are desperate to get in; the birds on the inside are trapped in the heat and the noise.

It is a machine designed for one thing: the continuation of the species.

They follow the rules. They march to the sea. They fish. They march back. They feed the chick. They huddle. They wait.

It is a life of absolute certainty. If you stay in the huddle, you live. If you follow the feet in front of you, you survive the winter.

But then, the camera catches something.

One of them… stops.

He is an Adélie penguin. He looks exactly like the thousands of others surrounding him. But while the colony moves in a rhythmic tide toward the open water—toward food, toward purpose, toward life—he pauses.

He stands completely still. A statue in a sea of motion.

He looks at the group, the chaotic safety of the mob. Then, he turns his head. He looks at the endless white horizon where the ice sheet stretches out for thousands of kilometers.

And he turns his back on safety.

He starts walking.

Alone.

He does not walk toward the sea. He walks directly toward the mountains. Toward the interior of the continent. Toward a place where there is no food, no water, no shelter, and no hope. Toward the place where nothing survives.

The documentary crew, led by Werner Herzog, watches in stunned silence. This isn't supposed to happen. It violates every biological imperative written into the bird’s DNA.

The scientists tried to stop him. They physically intervened. They dragged him back to the group. They thought he was lost. They thought he was disoriented by the sun or the magnetic fields. They thought, “We just need to point him in the right direction.”

But every time they let him go… he turned right back around.

He didn't run. He didn't panic. He just resumed his course.

He waddled away from the colony, away from the ocean, and back toward the mountains.

Seventy kilometers. Into the silence.

The camera zooms out. We see him as a tiny black speck against a cathedral of ice. He is marching with a terrifying determination. He is marching toward his own end.

The scientists called it a mistake.

They called it a malfunction.

They called it "insanity."

But I think they are wrong.

I think he was just tired.

Part II: The Soul Tired

We need to talk about "tired."

I don’t mean the way you feel after a session at the gym, where your muscles ache with a good, heavy soreness. I don’t mean the way you feel after a long flight, where your eyes are gritty and your brain feels like cotton wool. That is physical tiredness. That can be fixed with eight hours of sleep and a glass of water.

I’m talking about the other kind.

Soul tired.

You know the feeling. You might be feeling it right now as you read this on your phone, procrastinating the next task on your list.

It’s the alarm clock at 7 AM. That shrill, violent intrusion that doesn't just wake you up; it startles you into anxiety. It’s the realization, the moment your eyes open, that you have to do it all again.

It’s the traffic you sit in every single day. The red taillights stretching out in front of you like a string of angry beads. You look at the car next to you, and the driver looks just as hollow as you feel. You are both trapped in metal boxes, burning dinosaur bones to get to a building where you will sit in another box under fluorescent lights that hum.

It’s the smile you fake for people you don’t even like. The "Per my last email" passive-aggression. The mandatory birthday cake in the breakroom. The small talk about the weather.

It’s the path everyone told you to walk.

From the moment you were a child, you were placed in the huddle.

"Stay in line."

"Raise your hand to speak."

"Get good grades."

"Go to university."

"Get a stable job."

"Get a mortgage."

"Save for retirement."

"Keep your head down."

"Just survive."

We are social creatures, just like the penguins. We rely on the colony. We rely on the validation of others to tell us we are doing the right thing. If everyone else is swimming toward the ocean, then the ocean must be the right place to go. If everyone else is fighting for a promotion, then the promotion must be the prize.

So we march. We shuffle. We huddle against the cold of uncertainty.

But sometimes… surviving isn't enough.

Sometimes, the noise of the colony becomes unbearable. The squawking, the jostling, the smell of stagnation. You look around at the life you have built—the life that is "safe" and "correct"—and you realize it doesn’t belong to you. It belongs to the collective.

You are well-fed. You are warm. You are safe from the leopard seals.

But you are starving.

Part III: The Malfunction

When the scientists in Antarctica saw that penguin, they saw a broken machine.

In biology, an animal that acts against its survival instinct is considered "deranged." Evolution is supposed to ruthlessly weed out this behavior. If you don't want to eat and breed, you are an evolutionary dead end. You are a glitch in the code.

This is exactly how society treats us when we stop marching.

If you quit your high-paying job to paint landscapes, people ask if you are having a breakdown.

If you sell your house to live in a van, people whisper that you’ve lost your way.

If you simply stop smiling at the dinner party and say, "I am not happy," the room goes silent.

They try to drag you back to the group.

"You're just stressed," they say.

"Take a vacation. You'll feel better."

"Think about your pension."

"Don't be irresponsible."

They act like the scientists. They try to reorient you. They try to point you back toward the ocean, back toward the "food," back toward the safety of the known world. They do this out of love, usually. Or fear. Because if you walk away, it forces them to wonder why they are still standing in the cold.

But that penguin? He wasn’t confused.

Herzog, in his narration, captures the profound sorrow of the moment, but he also captures the dignity of it. The penguin pauses. He looks at the others. He makes a calculation.

He didn't want to die. I truly believe that. No sentient being wants to die.

He just couldn't pretend to live like that anymore.

He found something out there in the cold. Something the others didn't have.

Silence.

Can you imagine the silence of the Antarctic interior? No cars. No voices. No wind in the trees (because there are no trees). Just the absolute, crushing weight of peace.

Choice.

For the first time in his life, his direction was not dictated by the current or the flock. Every step he took toward the mountains was his own. He was the author of his own geography.

A destiny that was actually his.

We look at the footage and we scream at the screen. "Turn around!" we yell. "You're going to die!"

But is it better to live a thousand years in a huddle, never seeing anything but the back of the head in front of you? Or is it better to walk for one week, alone, seeing the mountains that no one else has ever seen?

Part IV: The Mountains

There is a term in Japanese: Hikikomori. It refers to people who withdraw from society, locking themselves away in their rooms for months or years. Society calls them sick.

There is a term in the corporate world: The Great Resignation. Millions of people walking away from "good" jobs. Economists call it a labor shortage.

There is a feeling in your chest right now. A tightness. A longing.

We label these things as problems. We treat them as malfunctions.

But what if they are just the penguin turning around?

I am not suggesting you walk into the snow to die. That is where the metaphor ends and reality begins. We are human beings, not flightless birds. We have options that the penguin did not have.

When we walk away from the huddle, we don’t have to walk toward death. We can walk toward a different kind of life.

But the mechanism is the same. The terror is the same.

To leave the path is to embrace the void.

When you finally quit that job, you feel a moment of pure vertigo. The ground disappears. The structure that held up your days—the alarm, the commute, the paycheck—vanishes. You are standing on the ice, and the horizon is endless.

It is terrifying. It is lonely.

Most of us will stay in the huddle.

We will complain about the cold. We will complain about the smell. We will post on social media about how much we hate Mondays. We will count down the days until Friday, and then the weeks until vacation, and then the years until retirement.

We will stay. Because it’s safe. Because the leopard seals are not in the huddle.

But once in a lifetime… maybe twice, if you are lucky… you get that feeling.

It starts as a whisper. A curiosity.

What is over there?

Who would I be if I wasn't this?

You look at the group. You see them arguing over politics, or money, or status. You see them climbing over each other to get slightly closer to the center of the circle.

And you realize: I don't want to be in the center.

So you stop.

You turn your back on the noise.

You stop following the feet in front of you.

And just… walk.

Maybe it looks crazy to them.

Maybe they’ll say you’re lost.

Maybe they will send the "scientists" (your parents, your boss, your bank manager) to drag you back.

"You can't be an artist," they'll say.

"You can't move to a new country now," they'll warn.

"You can't start over at 40."

But you’re not lost.

For that penguin, the mountains were a tomb. But for us? The mountains are just a metaphor for the unknown. And the unknown is the only place where new life can be found.

The mountains are the book you haven't written yet.

The mountains are the business you haven't started.

The mountains are the relationship that actually makes you feel seen.

The mountains are the quiet morning where you drink coffee and answer to no one.

Part V: The Horizon

I often wonder about the final moments of that penguin.

Dr. Ainley, the ecologist in the film, says that the penguin will march until his energy reserves are gone, and he will collapse. It is a tragic image.

But I like to imagine something else.

I like to imagine that for those seventy kilometers, he saw things of indescribable beauty.

He saw the way the light hits the blue ice of the glaciers, unshadowed by the bodies of other birds. He heard the sound of his own footsteps, a rhythm that belonged only to him. He felt the wind, not as an assault, but as a companion.

He died, yes. But he died free.

You are not a penguin. You have the luxury of returning. You can walk into the mountains, find what you need, and come back to build a new huddle—one of your own making.

But you have to take the first step.

You have to be willing to look like a malfunction. You have to be willing to be called "deranged." You have to be willing to withstand the intervention of the well-meaning people who are terrified of your freedom.

The world is noisy. The huddle is tight. The pressure to conform is heavier than the Antarctic ice sheet.

But look at the horizon.

Look at the mountains.

You are tired. I know you are. You are soul tired.

So stop marching.

Turn around.

Walk.

For the first time in your life, you’re finally heading somewhere real.

About the Creator

Frank Massey

Tech, AI, and social media writer with a passion for storytelling. I turn complex trends into engaging, relatable content. Exploring the future, one story at a time

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.