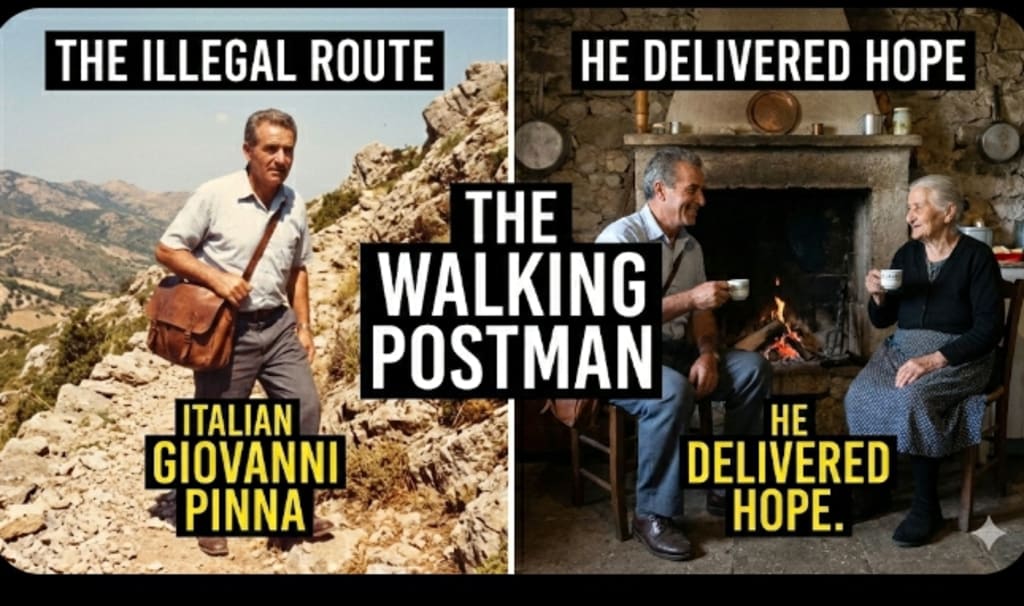

The Walker of the Ghost Villages: Giovanni Pinna’s Rebellion Against Silence

In the rugged mountains of Sardinia, modernization demanded that remote villages be cut off from the postal service. One postman decided that efficiency was not a good enough reason to let the elderly vanish from the world

The inspiring true story of Giovanni Pinna, the Italian postman who walked miles off-road every day to deliver mail to isolated mountain villages that the government had abandoned.

Introduction: The Silence of the Stones

Sardinia is an island of dualities. On the coast, there is the Emerald Coast—a playground of turquoise water, superyachts, and billionaires. But turn your back to the sea and walk inland, and you enter a different world.

You enter the Barbagia. The deep, mountainous heart of the island.

Here, the landscape is composed of granite, scrub brush, and silence. The villages cling to the sides of cliffs like barnacles. They are ancient places, built of stone, where the streets are too narrow for cars and the air smells of wild thyme and woodsmoke.

In the 1990s, a quiet tragedy was unfolding here. It was called spopolamento—depopulation. The young were leaving for the cities or the mainland. The schools were closing. The bakeries were shuttering.

The only people left were the old. The anziani. The stubborn, hardy generation that had survived wars and famines and refused to leave the houses where they were born.

But the modern world operates on metrics. It operates on "cost per unit" and "delivery density."

And by 1995, the metrics said that delivering mail to these high, remote hamlets was a waste of money. The roads were crumbling. The recipients were few.

The postal service made a decision. Service to the "zones beyond the pavement" would be suspended. Residents would have to come down to the nearest town to collect their mail.

For an 85-year-old widow with bad knees, "coming down to the nearest town" was not an inconvenience. It was an impossibility.

It was a sentence of total isolation.

But the postal service hadn't accounted for Giovanni Pinna.

Part I: The Man in the Blue Uniform

Giovanni was not a radical. He was not an activist. He was a man of the state, a civil servant who wore the blue uniform of the Poste Italiane.

He was in his late forties, a man with the weathered face of someone who has spent his life outdoors. He had strong legs and a back that didn't complain.

He had been assigned the route that covered the foothills and the upper ridges. For years, he had driven his yellow Fiat Panda as far as it would go, and then walked the last few hundred meters to the doorsteps.

Then came the order. Stop at the asphalt.

Giovanni held the paper in his hand. He looked at the map. He looked at the red line that marked the new boundary of his world.

He thought about Maria, who lived in the stone house at the top of the ridge. She waited for a letter from her grandson in Germany. It came once a month.

He thought about Antonio, the retired shepherd who lived alone with his dogs. Antonio received his pension check by mail. Without that check, he couldn't buy flour. He couldn't buy oil.

Giovanni looked at his supervisor.

"They can't come down," Giovanni said.

"That's not our problem," the supervisor replied, not unkindly. "We are a logistics company, Giovanni. We aren't a charity. The directive comes from Rome."

Giovanni nodded. He understood the chain of command. He understood the budget cuts.

He folded the paper and put it in his pocket.

"Understood," he said.

The next morning, Giovanni drove his Panda to the end of the asphalt. He turned off the engine.

The road ended. The dirt track began.

According to the rules, he should turn around. He should mark the letters "Undeliverable" or "Held at Depot."

Giovanni looked at the steep, winding path that disappeared into the chestnut trees.

He grabbed his leather satchel. He shoved the letters for Maria and Antonio inside. He locked the car.

And he started walking.

Part II: The Illegal Route

What Giovanni began that day was technically a breach of protocol. He was working off the clock. He was taking official government property (the mail) into unauthorized zones. If he twisted his ankle on those rocks, there would be no insurance coverage.

He didn't care.

The walk was not a leisurely stroll. The Sardinian interior is brutal. In the summer, the heat radiates off the granite, turning the valleys into ovens. In the winter, the Tramontana wind screams through the passes, carrying freezing rain that stings the face like needles.

The path to the furthest hamlet was seven kilometers. Uphill.

Giovanni walked it.

He developed a rhythm. Step, breath, step, breath. He listened to the cicadas. He watched for vipers in the grass.

When he arrived at the first house, a dog barked.

Maria came to the door. She was dressed in black, as she had been since her husband died twenty years prior. She leaned on a cane.

She looked at Giovanni. She looked at the sweat soaking through his shirt. She knew the mail had been canceled. The village priest had told them.

"Giovanni?" she asked, confused. "I thought..."

"I was in the neighborhood," Giovanni lied. He held out the envelope. "From Germany."

Maria took the letter. Her hands shook. It wasn't just paper. It was proof that she was remembered.

"Come in," she said. "Coffee."

You do not refuse coffee in Sardinia. It is an insult.

Giovanni sat in her dark, cool kitchen. He drank the strong, bitter espresso. He listened to her read the letter aloud.

He stayed for ten minutes.

Then he stood up. "I have to go to Antonio's."

"Go with God," she said.

He walked another three kilometers to Antonio’s.

That night, Giovanni went home. His feet ached. His uniform was dusty. He was exhausted.

The next morning, he did it again.

Part III: The Invisible Web

This went on for months. Then years.

Giovanni created a ghost route. It existed on no official map. It existed only in the muscles of his legs and the gratitude of the villagers.

He became a mule.

He realized that if he was walking all that way, carrying just a few envelopes seemed inefficient.

So he started asking questions before he left the town below.

"I'm going up to the ridge," he would tell the pharmacist. "Does Pietro need his blood pressure meds?"

"I'm going to see Elena," he would tell the grocer. "She’s out of coffee."

His bag grew heavier.

He carried medicine. He carried batteries for hearing aids. He carried fresh bread. He carried forms for the government—tax documents, census papers—and he helped the illiterate villagers fill them out.

He became the internet for people who had no electricity.

He brought news.

" The road is being repaired in the valley."

" The mayor is resigning."

" It’s going to rain on Tuesday."

He connected the severed dots.

Part IV: The Ministry of Presence

The physical exertion was immense, but the emotional labor was the true weight of the job.

Giovanni realized early on that the mail was secondary.

For many of these people, Giovanni was the only human being they saw for days, sometimes weeks.

Isolation is a physical disease. It eats at the mind. It makes the silence loud.

Giovanni didn't just drop the mail; he performed a "Ministry of Presence."

He developed a radar for trouble.

One Tuesday, he arrived at a house where an old man named Giuseppe lived. Usually, Giuseppe was sitting on the stone bench outside, whittling wood.

The bench was empty. The shutters were closed.

Giovanni knocked. Silence.

He tried the door. Unlocked.

He went in. The house was cold. The fire was dead.

He found Giuseppe in the bedroom, on the floor. He had fallen two days ago and broken his hip. He was dehydrated, delirious, unable to move.

Giovanni didn't panic. He gave the man water. He covered him with blankets.

Then he ran.

He ran the five kilometers back down the mountain to his car. He drove to the nearest phone. He called the ambulance. He guided the paramedics back up the trail.

They saved Giuseppe’s life.

If Giovanni had followed the rules—if he had stopped at the pavement—Giuseppe would have died alone on that floor.

Part V: The Storm

The winter of 1998 was harsh. A storm system stalled over the island, dumping snow on the peaks. The trails disappeared under white drifts.

The official advice on the radio was: Stay indoors. Do not travel.

Giovanni looked at the window. He thought about the pension checks in his bag. It was the first of the month.

If he didn't deliver them, the old folks couldn't pay the neighbor who brought them firewood. If they didn't have firewood, they would freeze.

Giovanni put on his heaviest coat. He wrapped his boots in plastic bags to keep the damp out.

He drove the Panda until it got stuck in a drift.

He got out. The wind was howling, a banshee scream that tore through the trees.

He started walking.

The snow was up to his knees. Every step was a battle. His face went numb. His eyelashes froze together.

He fell several times. He lost the path twice and had to navigate by the shape of the ridges.

It took him four hours to reach the first house.

When he knocked on the door, the woman who opened it screamed.

He looked like a yeti. He was covered in ice, shaking uncontrollably.

"Giovanni!" she cried. "Are you mad? You will die out there!"

He couldn't speak. His jaw was frozen. He just handed her the envelope with the pension check.

She pulled him inside. She put him by the fire. She made him soup. She rubbed his hands to bring the circulation back.

"Why?" she asked him, weeping. "Why would you do this for us?"

Giovanni waited until his teeth stopped chattering.

"Because it is the first of the month," he said simply. "And you have bills."

Part VI: The Discovery

For a long time, this was a secret. The villagers didn't tell the postal service because they were afraid Giovanni would get in trouble. Giovanni didn't tell anyone because he didn't want the praise.

But secrets in mountains have a way of echoing.

A hiker, a journalist from the mainland, was exploring the "lost villages" of Sardinia. He was looking for ruins.

Instead, on a high, desolate ridge, miles from the nearest road, he saw a man in a blue uniform walking with a heavy bag.

The journalist stopped him.

"Are you lost?" the journalist asked.

"No," Giovanni said. "I am working."

"Working? There is nothing out here."

"There are people out here," Giovanni corrected him.

The journalist followed him. He watched the interactions. He watched the coffee. He watched the tenderness.

He wrote the story. It appeared in a regional newspaper, then a national one.

THE ANGEL OF THE APENNINES.

THE POSTMAN WHO WALKS WHERE ROADS END.

People were shocked. In an era of efficiency, speed, and digital detachment, the image of a man walking through the snow to deliver a handwritten letter struck a chord.

The postal service was embarrassed, then proud. They couldn't fire a national hero. They offered him a van.

"The van won't fit on the trail," Giovanni said.

They offered him a promotion to a desk job.

"I cannot sit at a desk," Giovanni said. "Who would go up to Maria?"

Part VII: The Philosophy of the Step

When reporters came to interview him, they wanted a grand philosophy. They wanted him to talk about politics, or the neglect of the south, or the beauty of sacrifice.

Giovanni disappointed them. He was pragmatic.

"I walk because they are there," he said. "If I stop, they disappear. And it is not right for people to disappear while they are still alive."

He articulated something profound in his simplicity.

He understood that society is a contract. We agree to take care of each other. When the state breaks that contract because it is "too expensive," the individual must step in to repair it.

He wasn't just delivering mail. He was stitching the social fabric back together, one step at a time.

Part VIII: The Quiet Retirement

Giovanni walked for years. He walked until his knees began to protest, until his back began to stiffen.

Eventually, he had to retire.

The day he hung up his bag was a day of mourning in the high villages.

But he didn't leave them entirely. He still drove up on Sundays, in his own car, just to visit. Just to have coffee.

But time is undefeated.

Slowly, the lights in the high houses went out. Maria died. Antonio died. Giuseppe died.

The villages truly became ghost towns. The roofs collapsed. The briars took over the gardens.

Today, if you walk those paths, you will find ruins. You will find silence.

But you will also find a memory.

The locals who remain in the valley still talk about him. They tell their children about the man in blue who came out of the mist.

They don't talk about the mail. They don't remember the bills or the circulars.

They remember the sound of his boots.

Crunch. Crunch. Crunch.

The sound that meant: You are not forgotten.

Conclusion: The Radius of Responsibility

We often look for motivation in the stories of people who conquer the world. People who build empires, win gold medals, or make millions.

But Giovanni Pinna offers a different kind of motivation.

He teaches us about the "Radius of Responsibility."

We cannot fix the whole world. We cannot stop the march of time or the crumbling of economies.

But we can look at the people within our walking distance.

We can ask: Who is about to be forgotten?

Who is falling off the map?

And we can choose to walk toward them.

Giovanni Pinna didn't save the villages from extinction. He didn't stop the depopulation.

But he ensured that the final chapters of the people who lived there were written with dignity. He ensured that no one died thinking they didn't matter.

The Lesson

In a world that is obsessed with scaling up, sometimes the most radical thing you can do is scale down.

To focus on the one person in front of you.

To do the job that no one watches.

To take the walk that no one pays for.

Because the measure of a society isn't how it treats its rich and powerful. It is how many people it is willing to walk uphill to find, just to tell them:

"I see you. You are still here. And I have brought you news from the world."

About the Creator

Frank Massey

Tech, AI, and social media writer with a passion for storytelling. I turn complex trends into engaging, relatable content. Exploring the future, one story at a time

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.