The Quiet Contract of Asian America and the Architecture of Conditional Belonging

The system isn’t working

America presents itself as a system built on arrival. Come, contribute, comply and belonging will follow. 😊

The promise is implicit, rarely stated aloud, but reinforced through law, labor markets, education systems, and cultural mythology. For many Asian immigrants and their descendants, this promise has always functioned less as an invitation than as a conditional contract; one that demands output without guaranteeing protection.

The misalignment does not announce itself through spectacle. It operates through expectation. Asian communities were welcomed into America but not as people to be integrated; rather as labor to be utilized. From Chinese railroad workers to Filipino farmhands, from Japanese agriculturalists to South Asian medical professionals, Asian presence has often been filtered through usefulness. The system made room for hands, not voices. Productivity became a substitute for belonging. This orientation shaped everything that followed.

The economic system rewarded Asians who performed well within narrow parameters education, technical skill, professional compliance; while simultaneously excluding them from informal networks of power. Advancement was possible, but only in lanes that did not threaten existing hierarchies. Success was tolerated so long as it remained quiet, apolitical, and contained. The result was a paradox of visibility without recognition.

Asian migration to the United States did not begin as an act of free cultural exchange; it was the result of coordinated economic need colliding with global instability. In the mid-19th century, southern China particularly Guangdong province was experiencing profound disruption of the collapse of the Qing dynasty’s administrative stability, widespread famine, land shortages; and the devastation of the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), one of the deadliest civil conflicts in human history. The Qing dynasty's control was severely undermined by the aftermath of the First Opium War (1839–1842), which, along with the subsequent Treaty of Nanjing, damaged imperial prestige and fostered widespread anti-Manchu sentiment. Local administration became increasingly ineffective, leaving security in the hands of bandits, triads, and local militias.

A severe population boom with China's population reaching over 400 million by 1850 led to immense pressure on agricultural land, causing widespread poverty and land shortages. This was compounded by natural disasters and the disruption of local trade networks. While the epicenter of the Taiping Rebellion was in neighboring Guangxi and later the Yangtze Valley, the movement began in the south, with many followers coming from the Guangdong/Guangxi region. The rebellion created massive, bloody conflicts throughout the region, with significant loss of life in Guangdong, often pitting local Punti (Cantonese) against Hakka groups.

These conditions created a large population of displaced men with limited prospects at home, making them vulnerable to recruitment by foreign labor brokers. American railroad companies, mining interests, and agricultural enterprises actively capitalized on this instability, sending recruiters and intermediaries to Chinese port cities with promises of steady wages, temporary work, and eventual return.

Chinese laborers were not invited as future citizens; they were imported as a solution to labor shortages created by westward expansion, the California Gold Rush, and the construction of the transcontinental railroad. Once in the United States, they were assigned the most dangerous and underpaid work blasting tunnels through the Sierra Nevada, handling explosives, and enduring extreme conditions that white laborers often refused. When economic conditions shifted and white labor competition intensified, the system reframed these same workers from indispensable to undesirable.

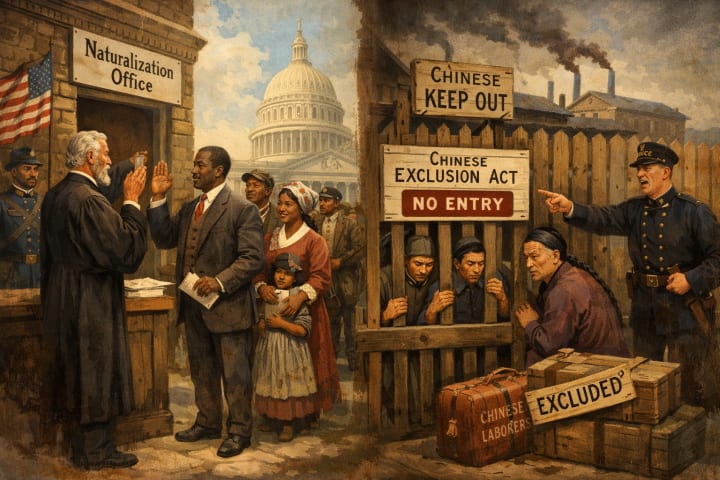

This shift was not merely social but legal, culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which halted Chinese immigration and barred Chinese residents from naturalization, formalizing a contradiction at the heart of the system that Chinese labor was welcomed but Chinese presence was not.

The same logic governed public health responses during the San Francisco plague outbreaks (sound familiar?), where Chinese neighborhoods were forcibly quarantined, residents were denied medical care, and propaganda framed Chinese bodies as inherently diseased despite officials knowing the plague was transmitted via rats arriving on commercial ships they chose not to halt.

These conditions were not incidental; they were tolerated. Japanese immigrants followed a similar trajectory, initially recruited as agricultural labor after Chinese exclusion, then targeted through measures like the Alien Land Laws (1913, 1920) that barred “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning land language designed explicitly to exclude Asians.

Citizenship and voting rights remained largely inaccessible until the McCarran–Walter Act of 1952, which finally allowed Asian immigrants to naturalize, though meaningful political inclusion lagged far behind legal permission. Each policy revision appeared corrective in isolation, yet collectively they reveal a system that oscillated between recruitment and rejection, labor inclusion and civic exclusion granting Asians access to work while withholding the protections, dignity, and political power that define belonging. These actions reveal a consistent pattern Asian bodies were admitted when economically useful, restricted when inconvenient, and scapegoated when fear demanded a target. The system did not malfunction it performed as designed, extracting labor while withholding permanence, protection, and political inclusion.

Here’s the timeline:

Naturalization Act of 1790 Limited U.S. citizenship to “free White persons” only. Asians were explicitly excluded from citizenship and voting by definition. This exclusion remained foundational for over 150 years.

1848–1870s mixed with the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) Chinese laborers recruited during the Gold Rush and railroad expansion. Allowed to work, barred from citizenship, political participation, and many legal protections. Courts repeatedly ruled Asians were “aliens ineligible for citizenship.

Naturalization Act of 1870 extended citizenship eligibility to people of African descent but Asians remained excluded, reinforcing a racial hierarchy of belonging; a post-Civil War legislation that allowed foreign-born individuals of African descent to naturalize, broadening rights beyond the 14th Amendment's birthright citizenship, while maintaining racial exclusions for others, specifically Asian immigrants.

1882 Chinese Exclusion Act First U.S. law to ban immigration based on race/nationality and this prohibited Chinese labor immigration and denied Chinese immigrants the ability to naturalize as citizens; and renewed and expanded repeatedly (1882–1943).

1885 Rock Springs Massacre in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory One of the deadliest episodes of anti-Chinese racial violence in U.S. history. On September 2, 1885, a mob of white miners attacked Chinese coal miners, killing at least 28 and burning down the town’s Chinese quarter. Survivors fled, and their homes and belongings were destroyed. The town’s newspaper later reported that “Nothing but heaps of smoking ruins mark the spot where Chinatown stood.” Despite the scale of the violence, few if any participants were ever held accountable, and the massacre was largely forgotten in mainstream histories for decades. (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2025/03/10/when-an-american-town-massacred-its-chinese-immigrants)

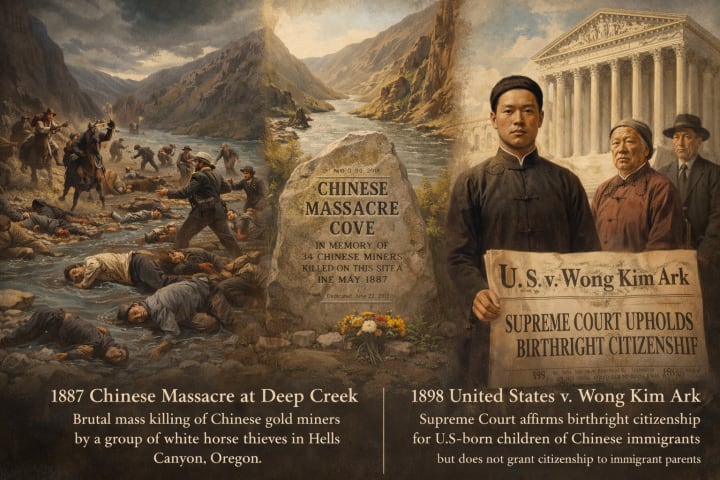

1887 The Chinese Massacre at Deep Creek (also called the Hells Canyon Massacre) Brutal racially motivated mass killing of Chinese gold miners in May 1887 on the Oregon side of the Snake River. A group of white horse thieves ambushed a remote mining camp in what is now known as Chinese Massacre Cove, killing between 31 and 34 Chinese miners who had been working there for gold; some bodies were thrown into the river and showed evidence of torture. The miners were employed by the Sam Yup Company of San Francisco, which later tried to pursue justice, but despite indictments and at least one confession, the accused were acquitted and no one was punished for the crime. This massacre is considered one of the worst acts of violence against Chinese immigrants in U.S. history and reflects the intense anti-Chinese prejudice of the period, which included other attacks, expulsions, and legal discrimination such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. In 2005, the site was officially named Chinese Massacre Cove, and in 2012 a memorial was installed to honor the victims.

1898 United States v. Wong Kim Ark Supreme Court affirmed birthright citizenship for children born in the U.S. to Chinese parents. It did not grant citizenship to immigrant parents themselves. The Supreme Court ruled in 1898 that anyone born in the United States including children of Chinese immigrants barred from naturalization; was a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment. This decision protected U.S.-born Asians from being stripped of citizenship and affirmed jus soli (citizenship by birthplace). However, it did not allow Asian immigrants to naturalize, did not change exclusion laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act, and did not open immigration. It simply clarified that U.S.-born Asians were citizens from birth.

Importantly, citizenship still did not equal guaranteed voting access. While U.S.-born Asian Americans were legally citizens after 1898 and could theoretically vote, many faced local barriers such as discriminatory registration practices, language exclusions, and intimidation especially in western states. So Wong Kim Ark established a constitutional floor for citizenship but like the 15th Amendment for Black Americans it took decades and further federal action before those rights were meaningfully protected in practice. (https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/169/649/)

1913 & 1920 Alien Land Laws (California and other states)

Barred “aliens ineligible for citizenship” (i.e., Asians) from owning land this specifically targeted Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and South Asian immigrants; and prevented long-term economic stability and intergenerational wealth. The Alien Land Laws, first enacted in California in 1913 and expanded in 1920, were state-level laws designed to exclude Asian immigrants from economic stability and permanence, even after United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898) affirmed birthright citizenship. These laws barred “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning land or leasing it long-term a phrase that was race-neutral on its face but explicitly targeted Asians, who were still barred from naturalization under federal law at the time. The 1920 amendments tightened the restrictions by banning leases entirely and prohibiting land ownership even through U.S.-born children, directly undermining the practical value of citizenship for Asian American families.

Crucially, these laws show how states adapted their methods of exclusion when federal law or the Constitution closed one door. Even though U.S.-born Asians were citizens after 1898, and even though Black Americans were citizens after the 14th Amendment, states used property law, local enforcement, and proxy racial categories to maintain racial hierarchy. The Alien Land Laws remained in effect in some states until they were struck down in 1948 (Oyama v. California) and 1952 (Fujii v. California) the same year the McCarran–Walter Act finally allowed Asian immigrants to naturalize. Together, these laws demonstrate that citizenship, voting rights, and economic belonging were deliberately decoupled, ensuring that formal legal status did not translate into real power or security for marginalized groups.

1924 The Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson–Reed Act)

This was one of the most explicitly racialized immigration laws in U.S. history. It established strict national-origin quotas based on the 1890 census, deliberately favoring Northern and Western Europeans while sharply limiting Southern and Eastern Europeans. Crucially, it completely barred immigration from Asia by defining Asians as “aliens ineligible for citizenship,” effectively extending and hardening earlier exclusion laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act. This law was grounded in eugenics and white-supremacist ideology, openly aimed at preserving the U.S. as a white, Anglo-Saxon nation.

The 1924 Act did not address citizenship or voting directly, but it froze racial hierarchy into immigration policy by ensuring that Asian communities could not grow through legal immigration, even as U.S.-born Asian Americans were citizens under United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898). When read alongside the Alien Land Laws, racial violence like the Rock Springs Massacre, and the later partial reversal in 1952, the Johnson–Reed Act shows how exclusion operated systemically: when citizenship could not be denied to U.S.-born Asians, the state restricted land ownership, immigration, and safety instead. It remained the backbone of U.S. immigration policy until it was dismantled by the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which finally rejected race-based national quotas.

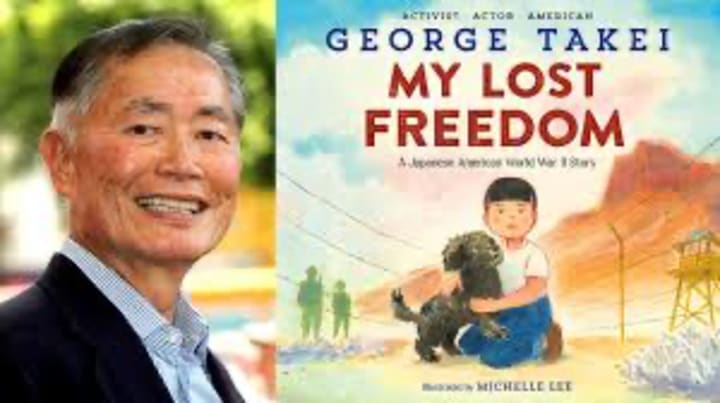

1942 Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government issued Executive Order 9066 (1942), authorizing the forced removal and incarceration of over 120,000 people of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens. Entire families were uprooted with little notice, stripped of property, businesses, and savings, and confined to inland camps under armed guard without charges, trials, or evidence of wrongdoing. The system did not distinguish between immigrants and citizens; ancestry alone was treated as sufficient cause. While Japanese Americans were the primary targets, the logic extended beyond them: Asian bodies broadly were cast as foreign, suspect, and interchangeable, reinforcing the idea that citizenship did not override race. Star Trek anyone?

German and Italian Americans were not subjected to mass incarceration at the same scale revealing how national security was selectively racialized; despite World War II including other countries partnering up with Hitler. Conditions within the camps barbed wire, overcrowding, inadequate medical care, exposure to extreme weather were justified as administrative necessity rather than acknowledged as incarceration; does this sound familiar? Even loyalty tests imposed on internees framed allegiance as something Asians had to repeatedly prove, rather than a status conferred by birth or law. Decades later, the government would formally concede the absence of military necessity through the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, offering an apology and reparations to surviving Japanese American internees. Yet the acknowledgment came long after livelihoods were destroyed and generations absorbed the lesson that Asian citizenship in America could be revoked in practice without being revoked in name.

1943 Magnuson Act Repealed Chinese Exclusion Act

The 1943 Magnuson Act (Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act) formally repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, ending the first and only U.S. law to ban immigration solely on the basis of race and nationality. It allowed Chinese immigrants to naturalize as U.S. citizens for the first time, marking a major symbolic shift after decades of exclusion, violence, and legal discrimination. The repeal was driven largely by World War II geopolitics, as China was a U.S. ally against Japan and the exclusion laws had become an international embarrassment.

However, the Magnuson Act was extremely limited in practice. It imposed a token annual quota of 105 Chinese immigrants, one of the smallest in U.S. immigration history, and did nothing to dismantle broader racialized immigration systems. Anti-Asian land laws, segregation, and social discrimination largely remained intact, and meaningful immigration from China was still effectively blocked until the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. In this sense, the Magnuson Act functioned less as full inclusion and more as a diplomatic gesture granting formal eligibility for citizenship while continuing to restrict population growth and structural equality.

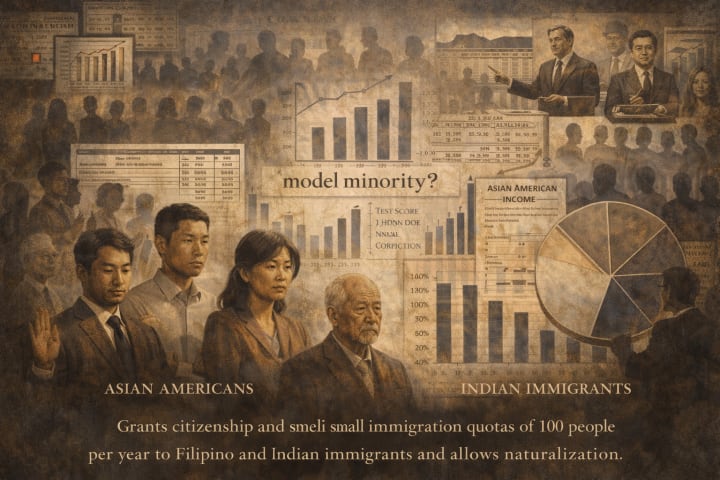

1946 Luce–Celler Act This granted citizenship rights to Filipino and Indian immigrants and small immigration quotas allowed. The 1946 Luce–Celler Act extended limited immigration and naturalization rights to Filipinos and Asian Indians, these were groups that had long occupied an ambiguous or excluded status under U.S. law. The act granted each group an annual immigration quota of 100 people and, crucially, made them eligible for naturalization, ending their classification as “aliens ineligible for citizenship.” Like the Magnuson Act of 1943, this change was shaped by World War II politics and U.S. foreign policy: the Philippines was moving toward independence (granted in 1946), and India was on the brink of independence from Britain (1947), making continued racial exclusion diplomatically untenable.

Filipinos had a unique path to the U.S. before 1946 because the Philippines was a U.S. colony after 1898. As U.S. nationals (not citizens), Filipinos were able to migrate freely to the mainland in the early 20th century to work in agriculture, canneries, and service jobs, particularly on the West Coast and in Hawaii. This changed with the Tydings–McDuffie Act of 1934, which reclassified Filipinos as aliens and sharply restricted immigration. The Luce–Celler Act partially reversed that exclusion by restoring limited immigration and naturalization rights. For Indians, immigration before 1946 had been extremely small and was effectively halted after the Supreme Court ruled in 1923 (Bhagat Singh Thind) that Indians were not “white” and therefore ineligible for citizenship. The Luce–Celler Act finally reopened a narrow legal door for Indian immigrants, laying early groundwork—though on a very small scale—for the larger waves of Filipino and Indian immigration that would only become possible after the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act abolished race-based quotas altogether.

1952 McCarran–Walter Act (Immigration and Nationality Act) This would become the first law to allow all Asian immigrants to naturalize and ended race-based naturalization restrictions; but it did not eliminate discriminatory quotas. This is the first moment Asian immigrants could broadly become U.S. Citizens, Vote and fully access legal protections tied to nationality. Although the Act removed race as a legal barrier to U.S. citizenship, making it the first law that allowed all Asian immigrants to naturalize. Before this, remember that most Asians were explicitly barred from becoming citizens, regardless of how long they lived in the United States. The 1952 law meant that Asian immigrants who met the requirements could become citizens and, once naturalized, could legally vote and access full legal protections tied to nationality. However, the act did not eliminate discriminatory national-origin quotas, so Asian immigration remained tightly restricted and relatively small in scale.

1965 Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart–Celler Act) This abolished national-origin quotas, opened large-scale immigration from Asia and fundamentally reshaped Asian America as we know it today. This Act addressed a different issue by abolishing national-origin quotas altogether, opening the door to large-scale immigration from Asia and reshaping Asian America demographically and culturally. This does not mean Asians gained voting rights before Black Americans. Black men were constitutionally granted the right to vote by the 15th Amendment in 1870, but that right was systematically suppressed for decades through violence and discriminatory state laws until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 enforced it. In short, Asians were excluded through citizenship laws, while Black Americans were excluded through the denial of enforcement different mechanisms; but both forms of systemic racial exclusion.

1965–Present

Asian Americans formally possess citizenship rights, voting rights, property ownership and equal protection under law (on paper) However lurking was informal exclusion, surveillance, and conditional belonging persist; and the legal inclusion did not erase cultural or political marginalization.

That was quite the path but Asian immigrants were allowed to work in America decades before they were allowed to belong to it.

Remember that Chinese laborers were not invited as future citizens; they were imported as a solution to labor shortages created by westward expansion, the California Gold Rush, and the construction of the transcontinental railroad. Once in the United States, they were assigned the most dangerous and underpaid work blasting tunnels through the Sierra Nevada, handling explosives, and enduring extreme conditions that white laborers often refused. When economic conditions shifted and white labor competition intensified, the system reframed these same workers from indispensable to undesirable.

This shift was not merely social but legal, culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which halted Chinese immigration and barred Chinese residents from naturalization, formalizing a contradiction at the heart of the system that Chinese labor was welcomed but Chinese presence was not.

As long as you behave

Asian Americans became statistically legible test scores, income brackets, employment sectors while remaining culturally and politically abstract. The system learned how to measure them, but not how to hear them. Data replaced dialogue. Representation became numerical rather than human. Let me elaborate, after formal exclusion laws began to fall, Asian Americans were no longer treated as legally invisible, but they were not truly understood or engaged either. Instead, institutions, schools, employers, policymakers began to recognize Asian Americans primarily through metrics: test scores, income levels, workforce participation, census categories. This made Asian Americans statistically legible (they could be counted, graphed, compared) while remaining culturally and politically abstract (their lived experiences, internal diversity, trauma, and dissent were ignored). The system learned how to measure Asian Americans but not how to listen to them. Quantitative data replaced qualitative dialogue, and “representation” became a matter of numbers rather than voice, agency, or narrative.

The “model minority” myth deepened this misalignment. It did not arise naturally from Asian American communities; it was produced by media, policymakers, and social science in the mid-20th century as a stabilizing story during the civil rights era. By framing Asian American survival under exclusion as evidence of cultural superiority or exceptional discipline, the myth erased structural barriers and redirected attention away from racism. Hardship was recast as personal virtue, silence as emotional maturity, and endurance as proof of contentment. In this way, compliance was rewarded, protest was discouraged, and Asian Americans were positioned not as full political subjects but as a comparative tool used to discipline other marginalized groups and to reassure the system that it did not need to change.

In this framing, struggle ceased to count as struggle if it did not resemble protest. The cultural system rewarded Asians for not demanding space. It praised adaptability while ignoring the cost of constant self-editing names shortened, accents softened, histories compressed into palatable anecdotes. Assimilation was encouraged, but never completed. No matter how fluent, successful, or law-abiding, Asian Americans remained provisional. Belonging was always one geopolitical shift away from revocation.

This pattern became most visible during moments of collective stress. Wars, pandemics, trade disputes, and geopolitical rivalries repeatedly reactivated a familiar script. In these moments, Asians were recast as external to the nation suspicious, interchangeable, and foreign regardless of citizenship, tenure, or generational depth. The distinction between immigrant and citizen collapsed under the weight of racialization. The system that had long benefited from Asian labor, technical expertise, and economic contribution revealed its limits: it could extract value, but it could not confer full moral belonging. Humanity, unlike productivity, remained conditional.

In earlier periods, invisibility functioned as a fragile form of protection. To be overlooked was to avoid scrutiny, hostility, or state attention. But when national anxiety intensified, that same invisibility became exposure. Without a firmly anchored narrative of belonging, Asians were easily repositioned as proxies for foreign threat. Social cohesion, once assumed, revealed itself as contingent a tolerance extended so long as global stability held and obedience remained legible.

The legal system reflected this instability with remarkable consistency. Immigration policy did not move along a linear path toward inclusion; instead, it oscillated between recruitment and restriction, often reversing course within a single decade. Skilled labor programs, refugee admissions, exclusionary quotas, surveillance regimes, and sudden enforcement crackdowns coexisted within the same policy ecosystem. For many Asian communities, this produced a permanent state of anticipatory anxiety. Legal status was not experienced as safety but as something provisional, revocable, and perpetually in need of documentation.

This instability did not end with naturalization. Citizenship, while legally conferred, did not reliably translate into psychological security. Even those born into citizenship absorbed the lesson that belonging was not self-sustaining. It had to be constantly reinforced through behavior. Status became something to manage rather than inhabit. The system failed to transmit a stable sense of national membership across generations, replacing it instead with inherited vigilance.

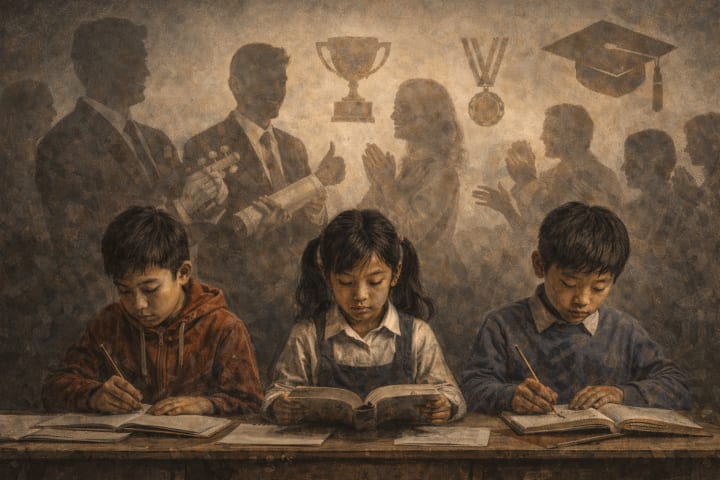

Children learned these rules early. They internalized the expectation to be exemplary without being disruptive, accomplished without being visible, and grateful without being secure. Success was permitted, encouraged and even but only insofar as it did not challenge dominant narratives or demand structural recognition. Emotional needs, political claims, and expressions of vulnerability were subtly discouraged. Silence was rewarded. Deference was misread as harmony.

Education played a central role in reproducing this pattern. Schools celebrated Asian academic achievement as evidence of meritocratic fairness, using aggregate success to obscure uneven access to resources and support. High performance was treated as proof that the system worked, rather than as a survival strategy within constrained conditions. This framing erased internal disparities across Asian communities, flattening distinct histories into a single metric of achievement.

Southeast Asian refugees shaped by war and displacement, undocumented students navigating legal precarity, and working-class families balancing multiple forms of labor were rendered statistically invisible. Their struggles did not fit the prevailing narrative of effortless success and were therefore excluded from policy concern. Vulnerability was masked by averages; need disappeared beneath accolades.

In this way, the system preserved a paradox where Asians were simultaneously held up as evidence of inclusion and denied the protections that true inclusion requires. Achievement substituted for belonging. Compliance stood in for security. And tolerance…never unconditional…remained subject to revocation the moment external pressures returned.

The System Flattened Complexity Into Convenience

Political structures followed suit. Asian Americans were frequently framed as politically inactive, a perception that justified their exclusion from serious engagement. Low outreach became a self-fulfilling prophecy. When participation did occur, it was often reactive and mobilized by crisis rather than cultivated by inclusion.

This left Asian communities in a structural limbo, being too successful to be seen as marginalized, too foreign to be fully trusted, too quiet to be prioritized. The misalignment is not rooted in individual prejudice alone. It is architectural. The system was not designed to integrate people whose presence complicates binary narratives of race, power, and resistance. Asian America unsettles the simplified moral math the system prefers.

So it responds by minimizing them. This is why the failure feels quiet. There is no singular breaking point. Instead, there is a steady accumulation of friction being present but peripheral, included but unconsidered, praised but unprotected. The system continues to function, and Asian Americans continue to function within it. That is precisely the problem. A system that relies on endurance as proof of alignment cannot distinguish between resilience and resignation.

The promise of America remains intact on paper. But for many Asian communities, it has always arrived with fine print contribute without complaint, adapt without acknowledgment, belong without assurance! The system does not collapse under this arrangement. It stabilizes itself. And in doing so, it leaves a growing population suspended between visibility and belonging, inside the system but never fully of it. Attention to that suspension is enough.

The persistence of Asian American achievement is often cited as proof that the system works. But survival under constraint is not evidence of fairness. It is evidence of adaptation. When success requires silence, and safety requires self-erasure, the metric itself is flawed. A system that only “works” when people absorb harm without complaint is not functioning; it is avoiding accountability. Any system that confuses endurance with consent, productivity with belonging, and silence with harmony is not inclusive by design; it is extractive by structure. America promises belonging through arrival. Asian America learned instead that belonging is conditional, renewable only through usefulness, and revocable without warning.

References

Merton, R. K. (1938). Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review, 3(5), 672–682.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2014). Racial formation in the United States (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Wu, F. H. (2002). Yellow: Race in America beyond Black and White. Basic Books.

Chou, R. S., & Feagin, J. R. (2015). The myth of the model minority: Asian Americans facing racism (2nd ed.). Paradigm Publishers.

Lee, J., & Zhou, M. (2015). The Asian American achievement paradox. Russell Sage Foundation.

Takaki, R. (1989). Strangers from a different shore: A history of Asian Americans. Little, Brown.

Chang, I. (2003). The Chinese in America: A narrative history. Viking.

Ngai, M. M. (2004). Impossible subjects: Illegal aliens and the making of modern America. Princeton University Press.

Chinese Exclusion Act, ch. 126, 22 Stat. 58 (1882).

Lee, E. (2003). At America’s gates: Chinese immigration during the exclusion era, 1882–1943. University of North Carolina Press.

Pfaelzer, J. (2007). Driven out: The forgotten war against Chinese Americans. University of California Press.

Kraut, A. M. (1994). Silent travelers: Germs, genes, and the “immigrant menace”. Johns Hopkins University Press.

New Yorker. (2025, March 10). When an American town massacred its Chinese immigrants.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2025/03/10/when-an-american-town-massacred-its-chinese-immigrants

Pfaelzer, J. (2016). The Chinese massacre at Hells Canyon. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 117(2), 224–259.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/169/649/

Motomura, H. (2006). Americans in waiting: The lost story of immigration and citizenship. Oxford University Press.

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948).

Fujii v. California, 38 Cal. 2d 718 (1952).

Daniels, R. (1993). Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 1850. University of Washington Press.

Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson–Reed Act), Pub. L. No. 68-139, 43 Stat. 153.

Ngai, M. M. (1999). The architecture of race in American immigration law: A reexamination of the Immigration Act of 1924. Journal of American History, 86(1), 67–92.

Kevles, D. J. (1985). In the name of eugenics. Harvard University Press.

Executive Order No. 9066, 7 Fed. Reg. 1407 (1942).

Daniels, R. (1993). Prisoners without trial: Japanese Americans in World War II. Hill and Wang.

Takei, G. (2019). They called us enemy. Top Shelf Productions.

Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Pub. L. No. 100-383, 102 Stat. 903.

Magnuson Act (Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act), Pub. L. No. 78-199, 57 Stat. 600 (1943).

Luce–Celler Act, Pub. L. No. 79-483, 60 Stat. 416 (1946).

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (McCarran–Walter Act), Pub. L. No. 82-414, 66 Stat. 163.

Tichenor, D. J. (2002). Dividing lines: The politics of immigration control in America. Princeton University Press.

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart–Celler Act), Pub. L. No. 89-236, 79 Stat. 911.

Zhou, M., & Lee, J. (2017). Hyper-selectivity and the remaking of culture: Understanding the Asian American achievement paradox. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 8(1), 7–15.

Poon, O. A., et al. (2016). Asian American and Pacific Islander students and the myth of the model minority. Teachers College Press.

Kim, C. J. (1999). The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics & Society, 27(1), 105–138.

Cho, S. (2020). Asian Americans and the politics of contagion. Harvard Civil Rights–Civil Liberties Law Review, 55, 1–45.

Ngai, M. M. (2004). Impossible subjects: Illegal aliens and the making of modern America. Princeton University Press.

About the Creator

Cadma

A sweetie pie with fire in her eyes

Instagram @CurlyCadma

TikTok @Cadmania

Www.YouTube.com/bittenappletv

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.