Mary Oliver: How Poverty Forged a Voice That Reshaped Modern Poetry

A life shaped by scarcity, long walks, devotion to observation, pursuit of meaning through daily practice

Mary Oliver entered childhood with little support or comfort. Her home life carried tension that weighed heavily on her, so she sought refuge outdoors whenever she could slip away. Fields, woods, tide pools, birdsong, creeks, shifting weather, all of it offered relief from an atmosphere that felt too tight for a growing spirit. Those early escapes created habits that defined her entire career. She learned to listen, to watch closely, to follow small traces of movement through grass or across water. She learned to trust perception more than conversation. That trust evolved into a poetic voice treasured by millions.

Finances during her youth rarely allowed ease. Food, time, space, encouragement, all arrived in limited supply. She discovered strength through survival, though she discovered purpose through attention. Poverty sharpened her senses because she had little choice. She grew aware of subtle changes in light or temperature during her walks. Leaves trembling near her feet, insects lifting through sunlit air, waves rearranging strips of seaweed, each detail shaped her understanding of the world. She felt pulled toward natural landscapes with a level of focus rarely taught in classrooms.

She found libraries early in life. Shelves filled with poetry offered guidance she had never received at home. She copied lines from books into notebooks, studying rhythm, tone, shape. She learned how a poem can rise from ordinary sights without elaborate language. Through repetition she built a foundation without formal instruction. Determination served her more reliably than any structured education could have at the time. Books offered voices that made her feel less alone. Poetry became less of a dream for her, more of a method for survival.

During her late teens she supported herself through physically demanding jobs that paid poorly. She woke early for long walks before each shift, then returned to writing with fatigue that strengthened her discipline. She used each day to refine her vision. Poverty forced her to work with whatever she had. She protected her creative time fiercely, even through exhaustion. These habits formed an unbreakable framework for her future.

When she eventually reached Provincetown, she encountered a landscape that illuminated everything she had built through years of self-study. Tide patterns, dune ridges, sudden salt air gusts, shifting bird calls, each element provided endless material for reflection. She walked for hours with a small notebook tucked inside her pocket. She wrote in short bursts whenever a phrase surfaced. She wrote again at home, shaping those fragments into poems that honored the world with striking clarity.

Her style grew distinct through patience, restraint, sincerity. She preferred plain language shaped with precision. She avoided cluttered phrasing because it distracted from the pulse of each poem. Readers sensed truth in her work because she approached each line with absolute fidelity to experience. She never forced an image. She never attempted to appear intellectually ornate. Her craft arose from looking deeply rather than decorating ideas with excess.

Scarcity from her early life influenced her devotion to small details. When money remains scarce, sunsets become gifts. When praise rarely arrives, a breeze across tall grass becomes a kind of companionship. She discovered significance in moments others skipped. This sensitivity became the signature of her work. It allowed readers to rediscover their own surroundings with new awareness.

Recognition arrived slowly, through journals that appreciated her focus. Then her collection American Primitive earned a Pulitzer Prize. This achievement expanded her audience significantly. Teachers introduced her poems to students. Readers repeated her lines during difficult phases of their lives. Her name began to circulate through literary communities, yet she maintained the same habits as before. Early morning walks. Afternoon writing sessions. Careful reading. Careful revision. She stayed loyal to the process that shaped her.

Success never shifted her priorities. She avoided spectacle. She avoided literary rivalries. She valued steadiness over prestige. Through her later books she explored mortality, spiritual longing, personal evolution, resilience. She wrote of loss with tenderness that comforted those facing their own grief. She wrote of desire with openness that felt grounded rather than sentimental. She wrote of presence with clarity that encouraged readers to step outside their routines.

Writers still seek lessons from her life because she showed that craft thrives through sustained attention rather than privilege. She began with almost zero external support. She forged a voice through persistence, curiosity, survival, long walks through fields that cost nothing. Creativity rose through her ability to notice. Her poems revealed how a person can build immense meaning from small daily rituals.

Her partnership with photographer Molly Malone Cook provided stability that her childhood lacked entirely. Their relationship offered continuity, affection, trust. Their home evolved into a creative sanctuary. Cook’s influence supported Oliver’s confidence, helping her reach depths she may have struggled to reach alone. That love played a central role in her maturity as a writer.

Through her later years, Oliver continued refining her perspective. She wrote of aging with candor. She wrote of contemplation with ease. She wrote of human longing through questions rather than proclamations. Her poems carried a kind of tenderness shaped through resilience rather than softness. She respected her readers enough to speak plainly, even when topics felt heavy.

Her legacy remains remarkable because it challenges assumptions about who becomes an influential poet. She emerged from poverty, trauma, household tension. She lacked formal training during formative years. She lacked mentors early on. She lacked comfort, safety, encouragement. Through perseverance she created work that comforts people across the world. Through daily walks she rooted herself in something larger than hardship. Through observation she cultivated gratitude for the world as it is.

Mary Oliver’s rise reveals that creativity develops through presence more reliably than through privilege. Those early walks in fields taught her how to pay attention. Those long hours in libraries taught her how to shape language. Those low-paying jobs taught her how to protect her craft with fierce loyalty. Her life shows that beginnings hold influence without dictating destiny. Through steady practice she built a voice that feels both intimate and universal.

Readers return to her work because it reminds them to slow down. Her poems offer steady hands during grief, transition, transformation. She invites reflection without pressure. She invites awe without grandeur. She invites truth through details that feel earned through lived experience.

Mary Oliver transformed hardship into vision. She entered adulthood with few advantages, though she constructed a career that reshaped modern poetry. She crafted poems that linger long after reading. She taught millions to notice the world with deeper care. Her life stands as proof that a writer’s greatest tool remains perception. Her work continues to welcome readers into moments they might have missed without her guidance.

Author's Note:

Below is one of Mary Oliver's poems:

The Summer Day

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean—

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down—

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

(Mary Oliver)

About the Creator

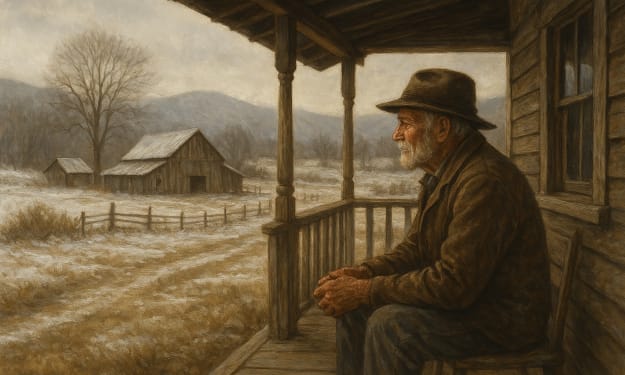

Tim Carmichael

Tim is an Appalachian poet and cookbook author. He writes about rural life, family, and the places he grew up around. His poetry and essays have appeared in Bloodroot and Coal Dust, his latest book.

Comments (2)

I remember hearing her name back in the 1980s and 1990s but I didn’t really know who she was. This was a great introduction to who she was. Well done Tim!

Thank you for sharing this. I only know a little of Oliver's work, but I didn't know anything about her background, so thank you for the insight.