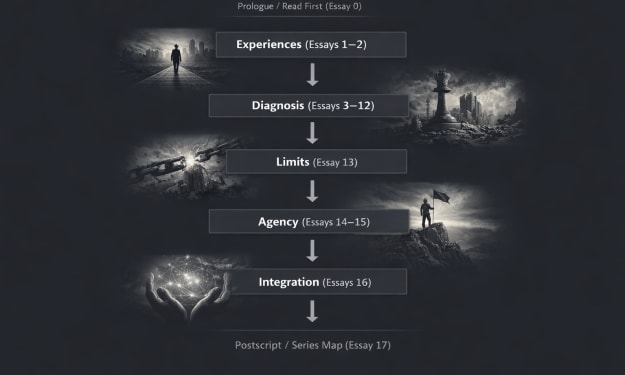

(5) The State Turned Inward

When Public Power Becomes a Tool of Internal Control

- The Original Purpose of State Power -

The fundamental justification for the state’s coercive power has always been outward-facing. Force was legitimized as a means of protecting the community from external threats, adjudicating disputes between citizens, and maintaining internal order where voluntary cooperation failed. In this framework, coercion was constrained by purpose. It existed to preserve the conditions under which ordinary life could continue, not to manage citizens as subjects. The state’s power was understood as dangerous but necessary, and therefore something to be limited, monitored, and distributed across institutions to prevent abuse.

That legitimacy depends on orientation. When coercive power is primarily directed outward or neutrally inward, it remains compatible with consent. When it becomes selectively inward-facing, aimed disproportionately at the population itself rather than at threats to the public interest, the moral character of the state changes. Coercion ceases to be protective and becomes managerial. The state no longer functions primarily as a guarantor of shared order, but as an enforcement arm for the preservation of internal structures of power.

- How Internal Orientation Quietly Emerges -

The inward turn of state power does not announce itself through open repression. It emerges incrementally as enforcement priorities shift and institutional incentives realign. As elite insulation increases and unequal enforcement becomes normalized, the coercive apparatus of the state must find targets that do not threaten its own stability. Enforcement therefore flows toward those without protection, influence, or leverage. Regulatory scrutiny, policing, taxation, surveillance, and administrative penalties increasingly focus downward, not because the public has become more dangerous, but because it is more manageable.

Over time, this reorientation becomes self-reinforcing. Agencies are rewarded for measurable compliance rather than substantive justice. Success is defined by enforcement volume, not legitimacy. Career advancement favors those who avoid politically sensitive cases and instead demonstrate effectiveness against low-risk targets. The state’s coercive capacity grows, but its application narrows. Power becomes increasingly asymmetric, not through explicit command, but through bureaucratic evolution.

- Why Coercion Becomes Asymmetric -

Once the state’s coercive tools are oriented inward, they cannot be applied evenly without destabilizing the structures they now serve. Equal application would expose insulated actors to risk, undermine elite protection, and threaten institutional continuity. As a result, coercion becomes asymmetric by necessity. The public experiences the state as omnipresent and exacting, while powerful actors experience it as distant and negotiable.

This asymmetry produces a profound shift in how citizens relate to authority. The law is no longer encountered primarily as a shared framework, but as a source of potential punishment. Compliance becomes defensive rather than cooperative. People begin to navigate the system strategically rather than trust it. This is not a breakdown of civic virtue. It is a rational adaptation to a system that has made coercion directional.

- The Role of Bureaucracy in Normalizing Control -

Bureaucracy plays a central role in disguising the inward turn of state power. Administrative processes fragment responsibility, obscure intent, and diffuse accountability. Decisions that would provoke resistance if made openly are instead implemented through regulation, guidance, interpretation, and enforcement discretion. Coercion is experienced not as force, but as inevitability. People are told the system has no choice, that rules must be followed, that procedures leave no room for judgment.

This normalization of control is more effective than overt repression because it preserves the appearance of neutrality. Citizens are managed through forms, deadlines, penalties, and compliance requirements rather than violence. Resistance is reframed as noncompliance rather than dissent. The state does not need to declare hostility toward its population. It only needs to make deviation costly and obedience routine.

- Why Dissent Is Recast as Risk -

As state power turns inward, dissent becomes increasingly framed as a threat rather than a corrective. Challenges to policy, enforcement, or legitimacy are treated not as signals of system failure, but as sources of instability. This reframing allows coercive measures to be justified as protective rather than punitive. Surveillance becomes safety. Enforcement becomes order. Suppression becomes responsibility.

This shift is not ideological. It is structural. A system that relies on internal coercion to maintain stability cannot tolerate challenges to its authority without undermining itself. As a result, dissent is pathologized, marginalized, or criminalized selectively. The goal is not total control, but deterrence. Enough pressure must be applied to discourage widespread challenge while preserving plausible deniability.

- Why This Does Not Require Authoritarian Intent -

The inward turn of state power does not require authoritarian ideology or explicit malice. It emerges from incentive alignment within existing institutions. Officials act to preserve careers, budgets, and legitimacy. Agencies act to justify their existence. Leaders act to maintain stability. None of these motivations are inherently tyrannical. Yet when combined within a structure that rewards insulation and punishes accountability, they produce coercive outcomes.

This is why focusing on intent misses the point. The problem is not that the state desires control for its own sake. It is that control becomes the path of least resistance in a system where legitimacy has eroded and accountability is uneven. Coercion fills the gap left by trust.

- How This Feels at the Personal Level -

For ordinary people, the inward turn of state power manifests as constant low-level pressure. Rules proliferate. Penalties increase. Compliance demands expand. Yet the sense of protection does not grow proportionally. People feel monitored rather than represented, managed rather than served. The state appears powerful in its ability to punish, but weak in its ability to solve underlying problems.

This produces a specific psychological effect. People become cautious, disengaged, and resentful without necessarily becoming rebellious. They adapt by minimizing exposure, avoiding attention, and lowering expectations. Civic life contracts. Participation becomes performative. Trust erodes quietly, replaced by resignation.

- Why This Is Unsustainable -

A state oriented inward against its own population can persist for long periods, but it cannot remain stable indefinitely. Coercion can enforce compliance, but it cannot generate legitimacy. Over time, the cost of enforcement rises as trust declines. More pressure is required to achieve the same level of order. This creates a feedback loop in which control must continuously expand to compensate for diminishing consent.

Eventually, the system reaches a point where coercion can no longer substitute for legitimacy. At that stage, outcomes become unpredictable. Collapse does not come from outrage alone, but from exhaustion. The system becomes too heavy, too rigid, and too brittle to adapt.

- Orientation Determines Legitimacy -

If the previous essay showed how unequal enforcement fractures law, this essay shows what follows when that fracture becomes operational. A state that directs its coercive power inward to preserve insulated structures ceases to function as a public institution in any meaningful sense. It becomes an apparatus of control.

Legitimacy is not restored through messaging or reform rhetoric. It is restored only when power is reoriented outward again, constrained by consequence, and bound by reciprocity. Without that shift, the state may endure, but it will no longer govern. It will manage decline.

About the Creator

Peter Thwing - Host of the FST Podcast

Peter unites intellect, wisdom, curiosity, and empathy —

Writing at the crossroads of faith, philosophy, and freedom —

Confronting confusion with clarity —

Guiding readers toward courage, conviction, and renewal —

With love, grace, and truth.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.