Why Did the Best Surgeon in History Kill Most of His Patients? Robert Liston, The Story of Surgery's Evolution

The Fastest Knife in the West End: The Revolutionary and Risky World of Victorian Surgery

Surgery isn’t something many of us look forward to. The very thought of it brings shudders, unless you're the woman who made headlines for spending millions to look like a cat. Yet, for most of us, the notion of going under the knife is something we dread. However, we should be thankful that we live in an era where anesthesia and hygiene are both considered essential practices in medicine. Imagine, for a moment, a time where surgery meant being wide awake, feeling every agonizing cut and incision, as a surgeon hacked through your body with a dirty saw. The terror of such an experience was the unfortunate reality of surgery in Victorian England.

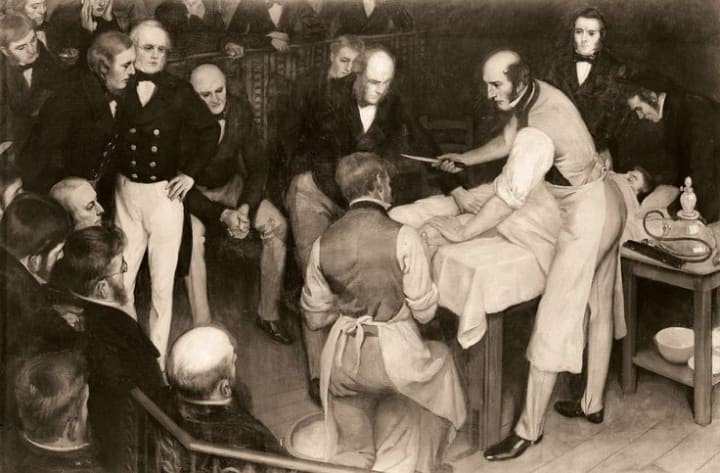

A Blood-Soaked Spectacle

Victorian operating theaters weren’t the sterile, silent rooms we’re familiar with today. Instead, they were crowded, filthy, and anything but private. Medical students, fellow surgeons, and even paying visitors would gather to watch a surgeon at work, much like a spectator sport. The theater, far from being a place of healing, was often an overcrowded auditorium reeking of blood and panic. In an era when anesthesia was unheard of, operations were more about brute force than finesse, and survival often depended on one thing—speed.

Surgeons of the time did their best to work quickly, knowing full well that every second increased the risk of their patient dying from shock or blood loss. The faster a procedure was completed, the better the chances of survival. And when it came to surgical speed, no one was faster than Robert Liston, known as the “fastest knife in the West End.”

The Lightning-Fast Surgeon

Born in 1794 in Scotland, Robert Liston was a man of great stature, both literally and metaphorically. Standing over six feet tall, with an imposing personality to match, Liston struck fear into the hearts of his students and peers alike. He studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, where his fascination with human anatomy began. As he rose through the ranks, he quickly developed a reputation as one of the best—and fastest—surgeons of his time.

Liston’s speed was legendary. It was claimed that he could amputate a limb in less than a minute. In an age where every second on the operating table was a matter of life and death, this speed earned him the title of "the Usain Bolt of the 19th-century medical world."

Before each surgery, Liston would walk across the blood-stained floor of the operating theater, holding his knife high in the air, before turning to his audience and bellowing his catchphrase, “Time me, gentlemen! Time me!” His audience, which included everyone from medical students to curious onlookers, would anxiously watch their pocket watches as he skillfully went to work. His speed was so great that he would often grip his blood-drenched scalpel between his teeth while sawing through a limb.

Mishaps and Mayhem

Despite his skill and speed, Liston’s surgical methods weren’t without their risks. In fact, the chaotic nature of Victorian surgery meant that accidents were almost inevitable. One of Liston’s more unfortunate blunders occurred when he was operating on a young boy. The aim was to remove a lump from the boy's neck, but as Liston began cutting, he realized—too late—that the lump was connected to a major artery. The boy tragically bled to death in front of a horrified audience.

On another occasion, Liston accidentally amputated not only his patient’s leg but also the man’s testicles in the process. As you might imagine, this was a rather painful mistake that did not go unnoticed. However, none of these mishaps compared to what has been dubbed the greatest surgical disaster in history.

One fateful day, Liston was in the middle of one of his famous high-speed amputations when things went terribly wrong. In his haste, he not only sliced off his patient's leg but also managed to chop off a few of his assistant’s fingers. To make matters worse, Liston’s knife accidentally slashed through the coat of an elderly spectator standing nearby. The elderly man, convinced he had been mortally wounded, fainted and later died of shock. Both the patient and Liston’s assistant would also die from infection, leading to a grim tally of three deaths in one surgery—a record that remains unmatched to this day.

A Gruesome Reality

Surgeons like Liston were celebrated for their speed, but hygiene was a different matter altogether. Washing hands or sterilizing surgical instruments was considered unnecessary, and the blood-soaked apron of a surgeon was seen as a badge of honor. In fact, the more congealed blood and gore a surgeon’s apron could hold, the more respected they were.

Patients recovering from surgery were often taken to overcrowded, unsanitary hospital wards where their fresh wounds were exposed to bacteria, leading to a high risk of gangrene or blood poisoning. It wasn’t uncommon for the air in these wards to be thick with the smell of rotting flesh and bodily fluids. Bedbugs infested the hospitals, and “bug destroyers” were often paid more than the surgeons themselves. In such dire conditions, it was no wonder that many patients died from infection after their surgeries.

The Search for Anesthesia

The unbearable agony of surgery made it clear that something had to change. Surgeons needed a way to nullify the pain that patients experienced on the operating table. For centuries, humans had experimented with various substances—opium, alcohol, and cannabis were all used to dull the senses. However, a reliable method for surgical anesthesia didn’t emerge until the early 19th century.

In Japan, surgeon Hanaoka Seishū performed the first recorded surgery with an anesthetic in 1804, using plant extracts. Meanwhile, in the West, doctors were experimenting with more eccentric methods, one of which was mesmerism—a technique developed by Franz Mesmer. Mesmer believed that an invisible force flowed through all living things, and by harnessing this force, a patient could be put into a deep, pain-free sleep. Though mesmerism briefly gained popularity, it was soon replaced by a more scientific approach.

Enter Ether: The Miracle Drug

The breakthrough came with the discovery of ether, an organic compound capable of inducing unconsciousness. Ether was first popularized during “ether frolics”—public gatherings where people would take turns inhaling ether to experience its effects. It wasn’t long before surgeons realized its potential for painless operations.

In 1846, American dentist William Morton made history by using ether during a tooth extraction. Although ether had been used earlier by another surgeon, Crawford Long, Morton’s demonstration is considered the first public use of ether as an anesthetic in surgery. The news spread quickly, and Robert Liston soon became one of the first surgeons to use ether during a major operation.

During his first ether-assisted surgery, Liston performed an amputation so quickly and painlessly that when the patient woke up, he had no idea the operation had already taken place. Liston triumphantly declared, “This Yankee dodge beats mesmerism hollow!” The age of anesthetic surgery had begun.

From Ether to Chloroform

Despite ether’s revolutionary impact, it had its downsides. The substance was highly flammable and irritated the lungs when inhaled. There was room for improvement, and it wasn’t long before Liston’s student, James Simpson, made a game-changing discovery. After experimenting with various chemicals, Simpson found that chloroform was a more effective and safer alternative to ether. Not only was chloroform non-flammable, but its effects lasted longer, allowing surgeons to perform more complex operations without fear of the patient waking up mid-surgery.

However, not everyone was convinced that anesthesia was a good idea. Some surgeons believed that patients needed to be awake during surgery to “fight for their lives.” This skepticism faded when Queen Victoria used chloroform during childbirth. Suddenly, the world’s most famous monarch had given anesthesia the royal seal of approval, and it became the standard practice for surgery.

The Fight Against Infection

While ether and chloroform solved the problem of surgical pain, the battle against post-surgical infection was far from over. In the mid-19th century, the leading theory on how disease spread was miasma theory—the idea that “bad air” caused illness. Hospitals were often ventilated to let in fresh air, but this did little to protect patients from infections that spread through unsanitary conditions.

It wasn’t until Louis Pasteur proposed his germ theory in 1861 that the medical community began to understand the true cause of infections. Germ theory suggested that microorganisms in the air, not the air itself, were responsible for spreading disease. This groundbreaking discovery laid the foundation for modern infection control practices.

The Triumph of Joseph Lister

Why Did the Best Surgeon in History Kill Most of His Patients? You'll definitely enjoy this!

One of Robert Liston’s students, Joseph Lister, was particularly inspired by Pasteur’s germ theory. He theorized that if he could keep the operating room free of germs, he could reduce the likelihood of infections after surgery. Lister’s solution came from an unlikely source—the Carlisle sewage works. He learned that carbolic acid was being used to neutralize the stench from the sewage, and he realized that in a diluted form, it could be used to kill germs during surgery.

Lister began to disinfect his surgical tools, bandages, and even his hands with carbolic acid. He also used a spray to pump the acid into the air during operations. Initially ridiculed for his methods, Lister soon saw dramatic results. In just three years, he reduced his patients' post-surgical death rate from almost 50% to 15. Hospitals today are bastions of good hygiene, with sterilization and cleanliness taking priority in every aspect of medical practice. The advancements made in surgery, anesthesia, and hygiene since the days of Robert Liston have been monumental, and it's hard to imagine that operations were once performed under such primitive and perilous conditions.

Why Speed Mattered: Robert Liston’s Role in Surgical Efficiency

But Liston's contributions shouldn't be downplayed, despite the occasional mishaps (like accidentally chopping off his assistant's fingers or slashing through an unlucky spectator's coat). In fact, Liston played a key role in ushering in a new era of surgical speed and efficiency—qualities that, while they may seem reckless now, were necessary for patient survival at the time. In a world without modern painkillers or proper sanitation, getting a procedure over with as quickly as possible was often the difference between life and death.

As for Liston’s other famous contemporaries and students, figures like James Simpson and Joseph Lister went on to revolutionize surgery even further. Simpson's discovery of chloroform as an anesthetic not only prolonged the length of surgeries but also made them far more bearable for the patients. The use of anesthesia meant that complex surgeries could be performed without the agonizing screams of patients echoing through the operating theater—something that must have been a game-changer, both for patients and surgeons alike.

Joseph Lister’s Fight Against Infection and the Birth of Antiseptic Surgery

Joseph Lister, on the other hand, took the fight against infection seriously and helped develop antiseptic techniques that would drastically reduce the mortality rates of surgical patients. His discovery that carbolic acid could kill germs was a revelation. No longer would surgeons be proud of their blood-soaked aprons as badges of honor; instead, they began to recognize the importance of cleanliness, sterilization, and the role microorganisms played in post-operative infections.

Lister’s use of carbolic acid to sterilize surgical instruments, bandages, and his own hands transformed the medical field. It showed that infection, a major cause of death after surgery, could be mitigated with proper hygiene practices. Though his methods were initially met with skepticism, they eventually gained widespread acceptance, and hospitals around the world began to implement his antiseptic practices.

While these practices were revolutionary, it’s important to acknowledge that the world of 19th-century surgery was still rife with challenges. The discovery of germs and the importance of sterilization were only the beginning. Surgeons and medical professionals had to battle against long-held beliefs and ingrained practices, such as miasma theory—the idea that diseases were caused by "bad air" or noxious gases rather than by microorganisms.

Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch: Pioneers in Germ Theory and Disease Control

Even though Louis Pasteur's germ theory was groundbreaking, it took time for the medical community to accept and apply it. In fact, the idea that tiny, invisible organisms could cause disease seemed preposterous to many. It took the work of other scientists, like Robert Koch, who isolated specific pathogens responsible for particular diseases, to finally give germ theory the recognition it deserved.

As these new scientific discoveries gained traction, they had a profound impact on surgery. Surgeons, who had once operated in filthy environments, now began to prioritize cleanliness and hygiene. Instruments were sterilized, and medical professionals started to wash their hands and wear clean clothing during procedures. These advancements reduced infection rates dramatically and set the foundation for modern surgery as we know it.

However, despite these advances, surgery in the 19th century was still a risky endeavor. While ether and chloroform made it possible for patients to undergo operations without being fully conscious, the risk of infection remained a constant threat. Even with improved techniques, the mortality rate for many surgeries was still alarmingly high by today's standards. Yet, the innovations of people like Liston, Simpson, and Lister laid the groundwork for future breakthroughs in medicine.

How Modern Medical Advancements Ensure Patient Safety and Precision

Over time, further developments in medical science continued to improve surgical outcomes. The invention of antibiotics in the 20th century provided another powerful weapon against infection, and the refinement of anesthesia allowed for even more complex and lengthy surgeries to be performed with minimal risk to the patient.

Today, we benefit from the cumulative knowledge and progress made over centuries of medical advancement. Modern hospitals are equipped with state-of-the-art technology, sterile operating rooms, and highly trained surgeons who can perform life-saving procedures with incredible precision. And while surgery is never something anyone looks forward to, the thought of undergoing an operation in the 21st century is far less terrifying than it would have been in the days of Liston.

Yet, we can’t forget how far we’ve come. The days when speed was valued over precision, when blood-soaked aprons were a surgeon’s pride, and when anesthesia was a pipe dream may seem like a distant past, but it wasn’t all that long ago. The contributions of Robert Liston, James Simpson, and Joseph Lister were instrumental in shaping the surgical practices we take for granted today.

Conclusion: How Far Surgery Has Come

In many ways, the history of surgery is a testament to human ingenuity and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. From Liston's rapid amputations to Lister's meticulous antiseptic procedures, each step forward in the field of surgery brought humanity closer to a future where medical care was safer, more effective, and—thankfully—less painful.

So, the next time you're in an operating room, remember: it wasn't always this way. Surgery used to be a brutal, bloody affair, performed with little regard for pain or cleanliness. And while we may never know exactly how many lives were saved by the speed of Robert Liston's knife, or how many infections were prevented by Joseph Lister's antiseptic methods, there's no doubt that their contributions were pivotal in the journey towards safer, more humane medical care.

In conclusion, the story of surgery’s evolution from its grisly, unsterilized roots to the precise and hygienic practice it is today is one that deserves to be remembered. It reminds us that even in the face of skepticism, progress is possible—and sometimes, it comes at the tip of a surgeon’s blade.

By the way, the next time you go under the knife, be grateful for the advances in anesthesia and sterilization—and perhaps spare a thought for Robert Liston, the "fastest knife in the West End," whose lightning-quick surgeries may have saved lives in a world before modern medicine caught up with the dangers of infection and the need for pain relief. Because let’s face it, nobody wants to be awake for that!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.