What ended the 'dark ages' in the early universe? New Webb data just brought us closer to solving the mystery

Astronomy & Space

Approximately 400,000 years following the Big Bang, the universe was enveloped in darkness. The initial burst of light from the universe's creation had dissipated, leaving space filled with dense hydrogen gas and devoid of any sources of illumination.

Gradually, over millions of years, gravity caused the gas to coalesce into clumps, eventually growing large enough to ignite. These clumps marked the emergence of the first stars.

Initially, the light emitted by these stars did not travel far, as a significant portion was absorbed by a hydrogen gas fog. However, as more stars formed, their combined light was sufficient to disperse the fog by "reionizing" the gas, resulting in the transparent universe adorned with bright points of light that we observe today.

The question of which stars were responsible for ending the dark era and initiating the "epoch of reionization" remained unanswered. In a study published in Nature, we utilized a massive galaxy cluster as a lens to examine faint remnants from this period, revealing that stars in small, dim dwarf galaxies likely played a crucial role in this monumental cosmic transformation.

What ended the dark ages?

Most astronomers have reached a consensus that galaxies played a crucial role in reionizing the universe, although the exact mechanism remained unclear. It is understood that stars within galaxies generate a significant amount of ionizing photons, but these photons must be able to penetrate the dust and gas within the galaxy in order to ionize hydrogen in the intergalactic space.

The question of which types of galaxies were capable of producing and emitting a sufficient number of photons to accomplish this task has remained unanswered. Some suggest that more unconventional objects such as large black holes may have been involved.

There are two main schools of thought within the galaxy theory.

The first group believes that massive galaxies were the primary source of ionizing photons. While these galaxies were scarce in the early universe, each one emitted a substantial amount of light. If a portion of this light managed to escape, it could have been adequate to reionize the universe.

On the other hand, the second group argues that it is more plausible to focus on the numerous smaller galaxies present in the early universe rather than the giant galaxies. Although each of these smaller galaxies would have produced less ionizing light individually, their collective numbers could have been sufficient to drive the epoch of reionization.

A magnifying glass 4 million lightyears wide

Looking into the early universe poses significant challenges. The scarcity of massive galaxies makes them difficult to locate, while smaller galaxies, although more abundant, are incredibly dim, making it arduous and costly to obtain high-quality data.

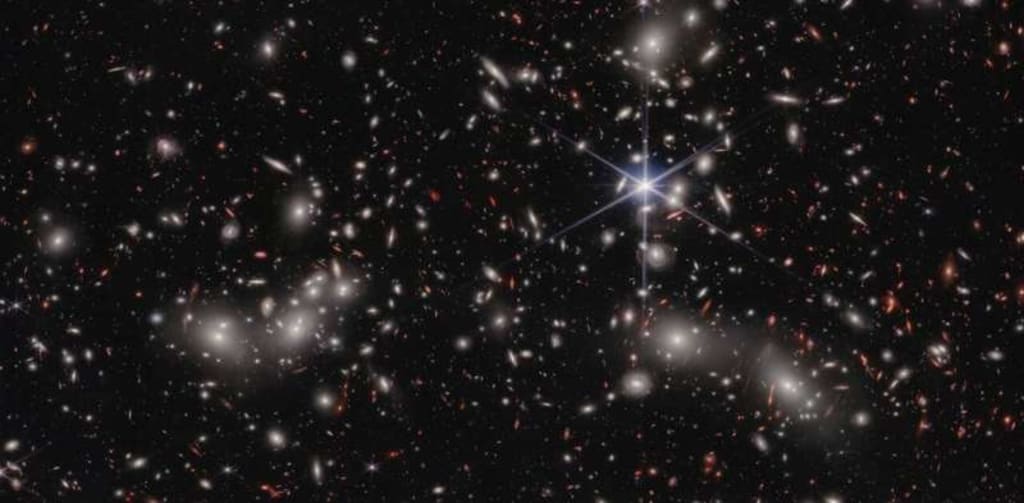

In our pursuit to observe the faintest galaxies, we employed Pandora's Cluster, an extensive collection of galaxies, as a powerful magnifying glass. The cluster's immense mass distorts space and time, enhancing the brightness of objects situated behind it.

As participants of the UNCOVER program, we utilized the James Webb Space Telescope to examine magnified infrared images of faint galaxies positioned beyond Pandora's Cluster.

Initially, we surveyed numerous galaxies before selecting a handful of exceptionally distant (and consequently ancient) ones for closer scrutiny. Due to the substantial expenses associated with such meticulous examination, we could only focus on eight galaxies in greater detail.

The bright gm this period, revealing that stars in small, dim dwarf galaxies likely played a crucial role in this monumental cosmic transformation.

The bright glow of hydrogen

We carefully selected a few sources that were approximately 0.5% as bright as our own Milky Way galaxy during that specific period. These sources were then examined for the distinct glow of ionized hydrogen. These galaxies were incredibly dim and could only be seen due to the magnifying effect of Pandora's Cluster.

Our observations not only confirmed the existence of these small galaxies in the early universe but also revealed that they emitted around four times more ionizing light than what is considered "normal". This finding exceeded our initial predictions based on our understanding of early star formation.

The significant amount of ionizing light produced by these galaxies implies that only a small portion of it would have been required to reionize the universe.

Previously, we believed that approximately 20% of all ionizing photons needed to escape from these smaller galaxies in order for them to be the primary contributors to reionization. However, our new data suggests that even just 5% would be sufficient, which aligns with the fraction of ionizing photons observed to escape from modern galaxies.

Therefore, we can confidently assert that these smaller galaxies may have played a substantial role in the epoch of reionization. However, it is important to note that our study was based on only eight galaxies, all located near a single line of sight. To validate our findings, we will need to examine different regions of the sky.

We have planned new observations that will focus on other large galaxy clusters in various parts of the universe. These observations aim to discover additional magnified, faint galaxies for further testing. If all goes according to plan, we anticipate having more answers in the coming years.

About the Creator

Sun Flora

Hello everyone. I am here to share latest articles about Technologies, Gadgets and other science related information. I hope this will be helpful for everyone.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.