The Portrait Left Behind

In the dust of forgotten wars, a faded photograph reopens wounds long buried beneath silence.

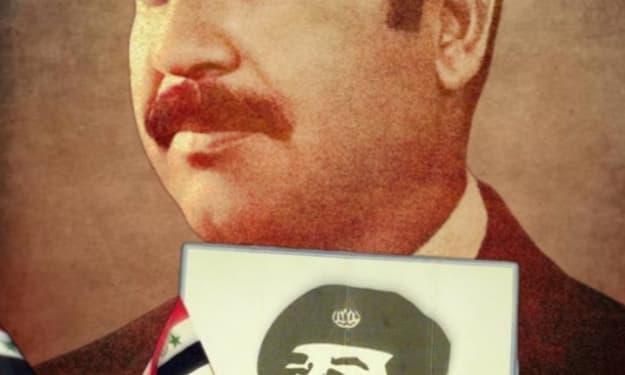

The photograph wasn’t even in color.

Just a black-and-white portrait, frayed at the corners, tucked away in the back of an old drawer at the Ankara State Archives. I found it by accident while researching 1950s municipal transport records. I had no business looking through personal effects, but something about the label caught my eye:

“Unknown Soldier’s Personal Effects – Returned from Korea, 1953.”

The young man in the photo couldn’t have been older than twenty. His uniform was clean but slightly oversized, as if he’d grown into it on the journey. He wore a gentle, almost sheepish smile—the kind you only see in people who have no idea they’re being remembered.

There was something haunting about that smile. Like it was waiting.

My grandmother used to talk about “the boys who never came back.” She’d whisper it sometimes, staring out the window as if she were waiting for someone to walk up the path, decades too late.

Korea was our “forgotten war,” overshadowed by Europe’s chaos and the Cold War’s shadow puppetry. But for a generation of Turkish families, it was heartbreak without closure. The village women knitted socks and sent dried figs in brown paper packages. The young men left with brass buttons and returned, when they did, in silence.

Or not at all.

I kept the photo.

I shouldn’t have. I signed paperwork stating that all items were to be returned to the archive box after examination. But I felt something irrational—something not quite mine.

Back home, I placed it on my desk, beside my books and tea-stained notes. I began calling him “the boy.” Not out loud. Just in my head.

That night, I dreamed of snow and smoke. Of marching feet and paper letters held tight in trembling hands. When I woke, the room smelled faintly of burned paper. I told myself it was my imagination. I told myself a lot of things.

The next day, I visited my grandmother.

She’s 92 now and forgets the present more easily than the past. But when I showed her the photograph, she went quiet.

“This one…” she whispered, tapping the edge with a trembling finger. “He wrote poems. Used to post them to his sister in Erzincan.”

She didn’t elaborate. I didn’t push.

Three days later, she handed me a bundle wrapped in floral cloth. Inside were two yellowed envelopes, brittle with time. No stamps. Just names, written in the kind of ink that fades like memory.

The handwriting matched the back of the photo. A signature:

“Metin A.”

The letters were fragments of a life paused mid-breath.

“We sleep in snow now. It softens the sound of the guns.”

“Tell Mother I dream of figs, and Father’s cough.”

“There is a boy from Manisa who hums in his sleep. I think he hears home.”

Simple. Uneventful. But in that restraint was a violence I couldn’t shake. There was no mention of fear, no anger. Just silence between the lines.

It reminded me of my grandfather, who never spoke of his own conscription except once—when I was eleven and asked if he’d ever fired a gun. He looked at me for a long time and said, “Only when no one was listening.”

I sent a copy of the letters to a professor who specialized in Turkish-Korean War correspondences. A week later, he replied with a single line:

“There’s no record of a Metin A. returning.”

That should have been the end.

But then, while flipping through a dusty newspaper archive from July 1953, I found a small article buried on page nine:

“Personal items of several unidentified Turkish soldiers were returned from Korea last week. Families are asked to visit the Ankara Memorial Center for potential identification.”

No list of names. Just a photo of medals in a velvet-lined box. In the corner, barely visible—a black-and-white portrait.

My portrait.

It’s strange how much silence can scream once you begin to hear it.

That weekend, I traveled to Erzincan. I had no clear purpose. No official reason. But I found an old cemetery on the eastern edge of the town, where pine trees swayed like mourners.

A woman in her seventies noticed me staring at a blank gravestone marked “Kayıp – 1953.”

“That’s for her brother,” she said, nodding toward a nearby bench where an older woman sat knitting.

“Metin?” I asked.

She looked surprised. Then, without a word, she pulled out an old, wrinkled letter from her purse. I recognized the handwriting instantly.

I didn’t say much. Just gave them the photo, the letters, and a soft apology I’m not sure was mine to make.

The older woman held the photograph like something sacred. She didn’t cry. She just stared at it for a long time before saying:

“He always smiled like that when he was about to say something clever.”

We sat in silence.

A breeze moved through the pines, whispering things only trees and sisters understand.

About the Creator

Ahmet Kıvanç Demirkıran

As a technology and innovation enthusiast, I aim to bring fresh perspectives to my readers, drawing from my experience.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.