The legend of the fiery battlefields - Le Trong Ton's generals

Anh hùng lực lượng vũ trang

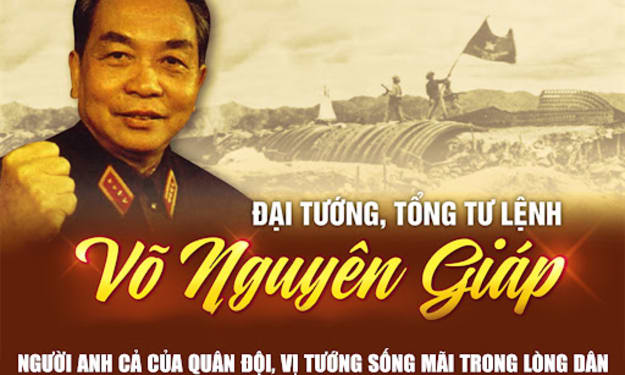

Thailand and Vietnam, despite not sharing a border, have a history of confrontations that have left a lasting impact on the Thai people. One notable conflict occurred during the 1972 Common Field Campaign, where Thai forces faced off against the legendary Vietnamese general Le Trong Tan. This battle became infamous for instilling a sense of fear in the Thai population, a sentiment that lingers even decades later. In the early 1970s, the war situation in the Indochina Peninsula intensified. The failure of the Lam Son 719 operation was a significant blow to the coalition of the US and South Vietnam, which was essentially a test of American military strategy. The objective was to determine if the Republic of Vietnam could defend itself without American ground troops. The outcome was unexpected; after three years and hundreds of billions of dollars invested, the final result was a defeat. Ultimately, it was the US Air Force and special forces that had to intervene to help the South Vietnamese military return to safety. Following the setback in 1972, the United States deployed troops to Laos, this time opting for the Royal Thai Army instead of the South Vietnamese forces. The hope was that utilizing local troops would lead to more effective combat against distant adversaries. However, this strategy proved flawed, as both the Royal Lao Army and the Thai forces displayed poor discipline and training. Their inability to conduct large-scale military operations resulted in an anticipated failure even before the conflict began. In July 1971, taking advantage of the rainy season, the United States and the Royal Lao Army initiated an operation to invade the Common Fields. Their plan was to secure this strategic area by retaking the airport and advancing along the trap line towards the Vietnam-Laos border. Unlike previous efforts, this time American forces included a larger contingent of Thai mercenaries. The combined forces consisted of 30 infantry battalions, including 18 from the Yellow Pau, 4 from the Royal Lao Army, and 8 from Thailand, along with 3 artillery battalions. A company of T28 aircraft and a platoon of armored vehicles received strong support from the US Air Force, including B52 and F-111 aircraft, alongside the liberation army, marking this as a significant battle. Special preparations were made to welcome the US Thai Lao coalition. Major General Le Trong Tan Sang, a party member and the deputy general directing the campaign, was well-known for his strict, fiery, and decisive leadership, which instilled fear in the Thai Lao coalition. Following their encounter with him, even the Thai media struggled to contain their praise for General Tan's strategic brilliance. The liberation army and the Lao pate army referred to this operation as a collective victory. Volunteer military units involved included division 316, regiment 866, and battalions 42, 25, and 26, which would be bolstered by units from division 312 and phase 335. The campaign also incorporated one ground artillery battalion, one anti-aircraft artillery battalion, two armored battalions, and several technical units. The Lao Revolutionary Armed Forces contributed nine infantry battalions, one artillery company, and three local armed teams. This campaign unfolded around Tet in the Year of the Rat, 1972. After assessing the situation on both sides, Le Trong Tan boldly declared his intention to engage in this battle, asserting that Thailand would still feel the repercussions three generations later. General Tan did not speak boastfully; rather, he devised a meticulous battle plan with thorough calculations. He accurately anticipated every move of the Thai Lao alliance merely by examining the map, positioning his troops in a masterful formation as if he had foreseen the battle's flow. His defensive strategy was well-considered, focusing on the center of the battlefield at Khun's main defense area, identifying weak spots, and establishing a basic forward defense area. He designated the Muong buc area and Sieu Khoang town for coordinated combat, planning to engage the enemy at optimal distances based on scientific assessments. The general's approach to force deployment aligned with the strengths of his selected units, and he meticulously outlined every detail of his strategy. The campaign that would cement his legacy commenced here, with the battle beginning on May 21, 1972, marked by the thunderous roar of B-52s overhead as they unleashed a barrage of iron bombs onto the traffic routes, ensuring total destruction. Air strikes persisted relentlessly throughout the day and night for four consecutive days until the Army advanced on May 25. Troops began to move from multiple directions, with the initial assault led by five battalions of the Royal Thai Army advancing from the west following four days of continuous bombardment. It was believed that the liberation army would withstand the attacks, though panic ensued due to overwhelming firepower. However, subsequent developments raised questions about the situation. General Tan established significant artillery positions, unleashing a barrage of H-72 rockets, 82mm and 120mm mortars, and 130mm explosives, followed by DKZ D40 and B41 weapons to eliminate remaining targets, alongside directional mines. Tanks thundered forward, propelling infantry ahead like a tsunami intent on engulfing the Thai forces. The Vietnamese Army's Regiment 174 actively thwarted counter-attacks, repelling numerous assaults by both the Lao and Thai armies. The Thai infantry, mostly from Laos, became alarmed upon witnessing the liberation army’s armored vehicles and began to scatter. Regiment 165, under Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Truong, executed a decisive assault, while Phu Tan led a successful offensive against the Thai army’s 141st regiment, targeting their command center in Phuton. American OV10 aircraft provided air support, illuminating the area and raining down fire to assist the disorganized units. Despite intense retaliation from Thai and Lao troops, supported by the United States, they could not withstand the fierce onslaught from the Vietnam-Laos coalition. After just five days of conflict, the Thai army and the Royal Lao army faced a significant defeat, as the lines blurred between attackers and defenders. In the second phase, from August 11 to September 10, the enemy shifted tactics, launching attacks on fields and roads from three directions: east, south, west, and northeast. They conducted airdrops in Phuken, targeting the 335th regiment from the southeast to assault Khang Muong at high point 1202. Two Lao battalions, reinforced by four tanks, attacked from the north towards North Phuket. A company from the 866th Regiment collaborated with two Lao teams to encircle the west bank of the Nam Ngu River. Unexpectedly, the enemy retreated toward the bridge over the Nguoi River, leading to an ambush that resulted in casualties, with 200 soldiers lost to floodwaters on September 3. The counter-attack concluded with the Vietnam-Laos alliance inflicting over 670 enemy deaths, capturing around a third of their forces, and confiscating numerous weapons. The situation drastically turned against the royal army. The Thai Royal Lao army and the incoming troops from the attacking side are now forced to retreat ahead of the defending forces. This marks the height of the offensive campaign. The defense led by Tan is proving ineffective. Helicopter transport tactics were employed as the army advanced westward. Field beams were simultaneously launched to disrupt and harass the rear but failed to yield results. The circumstances grew unfavorable for the Thai Laos US coalition as negotiations in Paris left the Americans with diminished hopes for victory, yet they still strived to capture a section in the South of the Common Field to create an illusion of success. During the third phase from September 11 to September 30, the Americans bolstered their forces and launched attacks west of the Common Field, aiming to seize land to claim victory while simultaneously deploying Commandos to Stalinois, complicating logistics for the liberation army, but with little success. In the fourth phase, from October 1 to November 15, the enemy amassed up to 60 battalions to strike the southern Beam Field, aiming to pressure the opposing forces. The political sabotage faction of the Vietnam-Laos coalition accurately assessed the intentions of the Thai-Lao US coalition, allowing them to proactively counter these assaults. The 3rd battalion of the 335th regiment of Vietnam launched an attack at the old village case 1172, thwarting enemy advances in Phu Xuyen Luong Phu. On October 14, the Vietnam-Laos coalition counter-attacked in the southern central area of the Field. By dawn on October 26, all attack fronts opened fire simultaneously, forcing the enemy to retreat back to the local area of Kha Kho Nam Chai Cham Field. From November 2 to 5, the Thai army was compelled to withdraw to maintain morale; not only were they unable to secure the South of the Common Field for negotiations, but the United States also suffered significant losses and was completely ousted from the region. The situation did not end there, as subsequent attacks against the enemy highlighted General Tan's leadership. At Huy Phu Nhu, the atmosphere was tense, with the Command and staff of Front 959 closely observing General Tan. His eyes were red as he moved around the village, occasionally studying a map on the cliff. He attentively scanned the area, displaying a look of anxiety as battlefield reports circulated regarding Dai Thang's return. Suddenly, he halted a conversation, contacting regiment unit 141 with an urgent tone, ordering the assault troops to withdraw. It seemed Mr. Tai’s comments had upset the general. Mr. Tuan approached, threatening to leave if he did not join. Following this, the soldiers surged forward in encouragement. A few Thai units remained to provide machine gun fire, prompting Nghi Binh to open fire and quickly devise a pursuit plan. However, the enemy was blocking their path, leading them to return to Long's lair and investigate reports of bright headlights along the northern road and forest gate area, while the southern route had fewer commanders. Vu appointed deputy commanders, with Dung Ma as head of the Operations Department. Huynh Le speculated that the enemy was retreating north, and someone suggested dividing the artillery to ensure effective fire. Mr. Le Trong Tan, however, ordered an intense concentration of fire along the southern route where there were fewer lights. Though there was hesitation among the officers, no one dared to oppose the order. The following day, Mr. Le Trong Tan dispatched someone to verify the situation. As anticipated, along the southern road, many enemies were indeed fleeing westward, which they attempted to clear, but while retreating, they faced artillery fire totaling 244 rounds. The Lao-Vietnamese coalition managed to capture 5,600 enemies and 1,137 soldiers surrendered. They shot down 130 aircraft, seized 136 artillery pieces, and by day’s end, the Lao army and people had approximately 400 soldiers captured and 139 soldiers taken. Meanwhile, 230 others engaged in battle suffered heavy casualties. Three battalions liberated 32 hamlets and three districts, recovering a significant amount of military equipment and weapons from the enemy before the inevitable defeat on the battlefield. At that time, US President Richard Nixon was compelled to agree to a ceasefire throughout Laos, with international supervision, accepting the 5-point proposal for negotiations aimed at achieving a peaceful resolution in Laos. General Tan’s assertion that this battle would instill lasting fear in Thailand for generations resonated profoundly.

Comments (2)

Thanks for sharing

Interesting