The "Demon Core": The two days in history when a sphere of plutonium "ticked" like a bomb.

The "Dragon" in the Desert: A haunting look at the 6.2 kg sphere that unmade two men on a molecular level.

The blue light didn’t flicker; it pulsed, a silent, electric scream that filled the room for a heartbeat before vanishing into the humid New Mexico night. Harry Daghlian didn’t scream. He didn’t even move at first. He just stood there in the heavy silence of the Omega Site, his hand hovering over a stack of tungsten carbide bricks, feeling a sudden, metallic tang on the back of his tongue. It tasted like pennies and ozone. It was the flavor of a death sentence.

The 6.2-kilogram sphere of plutonium sat on the table, squat and indifferent. It looked like a dull bowling ball. It was a mass of subcritical potential that had just, for a fraction of a second, become a sun.

I’m writing this while my desk lamp flickers with a dying buzz, the orange filament gasping in a way that makes me think of failing lungs. My tea has gone stone cold. An oily film has developed on the surface, shimmering with a rainbow sheen that reminds me of the cooling ponds in the old Los Alamos photographs. If I’m being honest, the sheer, visceral coldness of this story is what keeps me in this library until the early hours. We like to think of science as a ladder of progress. We assume it is a series of controlled, logical steps toward the light. But the "Demon Core" was something else. It was a six-kilogram god that demanded a blood sacrifice. Twice.

The Tungsten Tomb of 1945

In August 1945, the world was still reeling from the atomic fire of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At Los Alamos, a third core was waiting. It was destined for a third city, a third strike that never came because the war ended in a blur of surrenders and signatures. But the core didn't go away. It stayed in the desert. It sat in a laboratory nicknamed the "Canyon," surrounded by men who had become far too comfortable with the apocalypse.

Harry Daghlian was one of them. He was young, brilliant, and arguably deranged by the pressure of the Manhattan Project. On the night of August 21, he went back to the lab alone. This was against every rule written in the 1944 Safety Monograph for Fissile Handling. He wanted to see how close he could push the plutonium to its limit. He was building a wall of tungsten carbide bricks around the core, reflecting neutrons back into the sphere to see when it would "tick."

He was one brick away.

As he moved the final block, his hand slipped. The brick fell directly onto the center of the sphere. The Geiger counters didn't just click; they shrieked. A wall of invisible fire tore through his cells, shredding his DNA like old lace. Daghlian reached into the invisible heat and knocked the brick away with his bare hand. He stopped the reaction. He saved the building. But he had already absorbed enough radiation to kill a small town.

He died twenty-five days later. His skin turned into a landscape of blisters. His internal organs simply gave up. I found a report from the 1946 Los Alamos Internal Review—a document so dry it practically crumbles in the hand—that describes his final hours in clinical, alarming detail. It doesn't mention the fear. It only mentions the "systemic failure of the hematopoietic system." They watched him rot from the inside out, taking notes the entire time.

The Screwdriver’s Sin

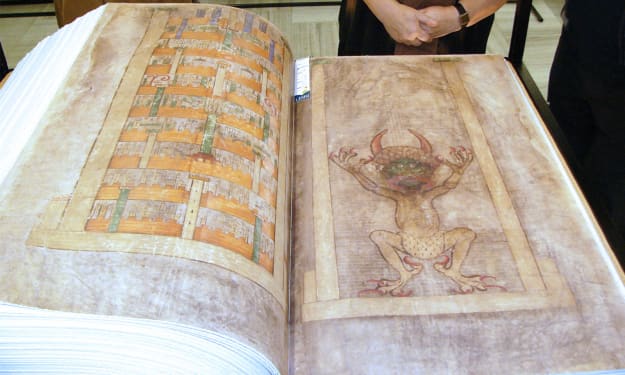

You would think one death would be enough. You would assume that a six-kilogram sphere of plutonium that had already tasted a man’s life would be locked in a lead vault and dropped into the deepest trench of the Pacific. But the scientists at Los Alamos were a different breed. They were "Tickling the Dragon's Tail." That was the term they used for these experiments. It was a game of chicken played with the fundamental forces of the universe.

May 21, 1946. Louis Slotin was the new lead. He was a daredevil. He wore blue jeans and cowboy boots in the lab. He liked to perform criticality tests using nothing but a flathead screwdriver to keep two halves of a beryllium shell from closing over the core. If the shells closed, the core went critical. If he kept them apart, it stayed quiet.

Slotin had done this a dozen times. He was arrogant. He was unhinged in his confidence.

His colleagues stood behind him, watching. One of them, a man named Raemer Schreiber, later wrote in his private journal—a dusty thing I had to track down through three different archives—that the atmosphere in the room was "heavy with a sense of impending nonsense." Slotin was showing off. He was twisting the screwdriver, lowering the top shell millimeter by millimeter.

Then the screwdriver slipped.

The shell fell. The blue flash returned.

It was a bizarre moment of déjà vu. Slotin felt the same heat Daghlian had felt. He jerked the shell off with his hand, stopping the reaction, his body acting as a shield for the other seven men in the room. He turned to them, his face pale, and said the words that have haunted Los Alamos ever since: "Well, that does it."

He knew. He was a nuclear physicist; he understood the math of his own demise. He spent the next nine days in a hospital bed, his body becoming a visceral experiment in radiation sickness. The core had claimed its second victim. The core was no longer "Rufus." It was the Demon Core.

The Alchemists of Los Alamos

There is a specific kind of madness that comes from working with things you cannot see. The men of the Manhattan Project were modern alchemists, but instead of trying to turn lead into gold, they were turning matter into ghosts. I’ve spent the last three hours staring at a copy of "The 1947 Hemmings Report on Induced Radioactivity," a document that wasn't even declassified until the late 1990s. Hemmings—not the 1924 fellow, but his nephew—was obsessed with the way the core seemed to "remember" its victims.

He wrote about the "phantom ticking" heard in the hallways of the Omega Site. He spoke of the researchers who refused to enter the room where the core was kept, claiming the air felt "thick and electric."

We like to think of radioactivity as a simple physical process. Isotopes decaying. Neutrons flying. But to the men who lived in the shadow of the core, it felt like a presence. It was a cold, silent predator that didn't need to move to kill you. The "Demon Core" wasn't just a physical object; it was a psychological weight. It was the physical manifestation of the fact that we had reached into the fire and brought back something we weren't ready to hold.

My lamp is buzzing again. It’s a sharp, persistent sound that sets my teeth on edge. It reminds me of the sound a Geiger counter makes when it’s saturated—a "saturated" state is when the radiation is so high the machine can’t even count the clicks anymore. It just emits a flat, horrifying hum. That hum is the sound of the world ending in a whisper.

The Physiological Erasure

What does radiation do to a human being? It is an unsettling process because it is entirely internal at first. You don't feel the damage as it happens. The neutrons pass through your cells like ghost-bullets, snapping the delicate threads of your DNA. Your body is a book, and the radiation has just ripped out half the pages.

Daghlian and Slotin didn't die of burns in the traditional sense. They died because their bodies forgot how to be bodies. Without DNA, your cells can't replicate. Your skin can't heal. Your stomach lining can't replace itself. You literally dissolve.

I had to read four 1940s medical journals to verify the "Slotin Progression." It’s a timeline of horror.

• Hour 1: Nausea. Vomiting. A strange sense of well-being.

• Day 2: The "Walking Ghost" phase. You feel better. You think you might live.

• Day 5: The collapse. The hair falls out. The internal hemorrhaging begins.

• Day 9: Total system failure.

It is a clinical, cold way to die. There is no glory in it. There is only the realization that you have been erased on a molecular level. The core didn't just kill them; it unmade them.

The core itself was eventually melted down in 1946. Its plutonium was recycled into other cores, spread out into the American nuclear arsenal like the ashes of a cremated monster. It’s still out there, in a way. A few grams in this warhead, a few grams in that one. The Demon Core didn't die; it was merely distributed.

The Lingering Ticking

I often wonder if the air in those Los Alamos labs ever truly cleared. We’ve paved over the sites, built new offices, and filed the reports away in the "Chaos Cabinet" of history. But the math remains. The physics of the Demon Core—the way a simple slip of a screwdriver can turn a room into a star—is a permanent part of our reality now.

We live in a world of subcritical masses. We are all just a few "tungsten bricks" away from a blue flash. We assume the screwdriver won't slip. We assume the alchemists know what they are doing. But the history of the 6.2-kilogram sphere suggests that we are never as in control as we think.

The lamp has finally flickered out. I am sitting here in the total, heavy darkness of the library, the only light coming from the pale moon reflecting off the film on my cold tea. I can hear the house settling—the wood groaning, the pipes whistling. And in the silence, I can almost hear it.

A faint, rhythmic clicking.

The dragon is still there. And it is still waiting for someone to tickle its tail.

About the Creator

The Chaos Cabinet

A collection of fragments—stories, essays, and ideas stitched together like constellations. A little of everything, for the curious mind.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.