The Curse of Kuru: A Tribe, a Brain Disease, and the Price of Ritualistic Cannibalism

why you shouldn't be a cannibal literally

Deep in the highlands of Papua New Guinea lies a tragic chapter in human history—one that merges ritual, culture, disease, and death in a tale as fascinating as it is horrifying. It centers on the Fore people (pronounced "for-ay"), a remote tribe whose unique mortuary rituals gave rise to a deadly brain disease known as Kuru—a term derived from the Fore word meaning "to shake."

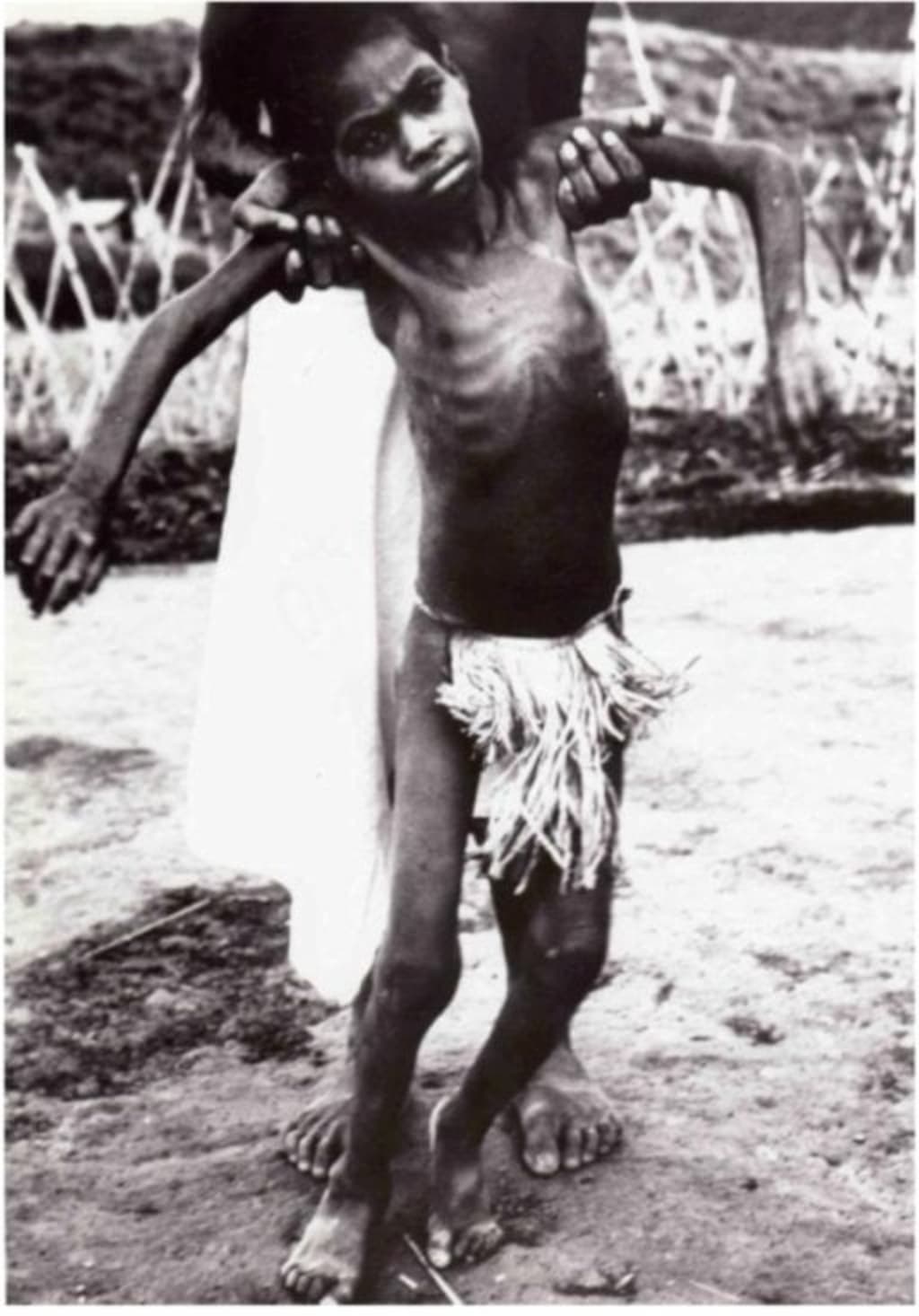

Though the tribe was unaware, their sacred practice of consuming the dead in funerary rites was feeding a nightmare. This bizarre condition, characterized by uncontrollable tremors, laughter, and a gruesome decline into death, once claimed hundreds of lives, mostly women and children. It would take decades of research and cultural understanding to unveil the truth: the Fore were victims of their own love and reverence for the deceased.

Ritual Cannibalism: A Sacred Practice

Among the Fore, the dead were not buried or cremated in the typical Western sense. Instead, a deep spiritual obligation compelled the tribe to partake in endocannibalism—the ritualistic consumption of their dead relatives. Far from barbaric in intent, this practice was an act of mourning and respect, ensuring that the spirit of the deceased lived on within the community.

Women and children bore the brunt of this responsibility. While men often avoided the practice, the females would prepare and eat the body, including the brain. It was this crucial detail—the consumption of human neural tissue—that would unknowingly introduce a deadly pathogen into their midst.

The Symptoms of Kuru: Death with a Smile

The term “Kuru” was given by the Fore themselves due to the shivering and shaking seen in its victims. But this was no ordinary neurological disorder.

Kuru symptoms progressed in three terrifying stages:

Ambulant Stage: The victim would begin to lose coordination, experiencing difficulty in walking, involuntary tremors, and muscle stiffness.

Sedentary Stage: Patients could no longer stand without support. Emotional instability would emerge, often with bouts of uncontrollable laughter, giving Kuru the nickname “the laughing death.”

Terminal Stage: In this final phase, the individual was completely bedridden, unable to swallow, speak, or respond, eventually dying in a coma-like state.

From onset to death, the disease could last anywhere from three months to a year. It was always fatal. Between the 1950s and the late 1960s, Kuru killed over 1,100 members of the Fore tribe, mostly women and children.

The Medical Mystery: Enter the Scientists

In the 1950s, Australian government patrol officers began noticing the high mortality rate among the Fore. Curious and alarmed, they reached out to researchers, and by 1957, American physician Dr. Carleton Gajdusek took up the challenge of investigating Kuru.

Gajdusek suspected that the disease was not bacterial or viral but something even stranger. The breakthrough came when he and his team managed to transmit Kuru to chimpanzees by injecting them with brain tissue from infected humans. The disease took years to develop—a key trait of what would become known as prion diseases.

For his work, Gajdusek won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1976. But there was more to uncover.

The Real Culprit: Prions

Kuru belongs to a family of diseases caused by prions—misfolded proteins that trigger a cascade of abnormal folding in other proteins, especially in brain tissue. Prions are not alive in the traditional sense; they contain no DNA or RNA. Yet, they can spread like wildfire once introduced into a host.

Other prion diseases include Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (CJD), Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE, or "mad cow disease"), and Fatal Familial Insomnia. All are degenerative, untreatable, and fatal.

Kuru was the first known human prion disease caused by ritualistic behavior, and it reshaped our understanding of infectious disease.

The Decline of Kuru: A Cultural Shift

In the early 1960s, under the guidance of colonial officials and researchers, the Fore gradually abandoned the practice of endocannibalism. As this cultural shift took root, the incidence of Kuru began to plummet.

However, due to the extremely long incubation period—sometimes as long as 30 years or more—cases continued to emerge even decades later. The last known Kuru victim died in 2009, marking the likely end of the disease as a public health threat.

Lessons from the Edge of Civilization

The Kuru saga is more than a strange anthropological footnote. It provided the foundation for understanding neurodegenerative diseases, contributed to the regulation of blood donations and surgical sterilization practices worldwide, and underscored how cultural behaviors can influence epidemiology.

Yet the tragedy also illuminates something profoundly human: the danger of judging ancient customs through modern lenses. To the Fore, consuming a loved one was the highest form of respect. They were not cannibals in the horror-movie sense—they were mourners, healers, and spiritual stewards of their community.

Final Thoughts

I was an 11 year old kid when first learned about the kuru disease. it was haunting. it was also my first time learning humans ate humans. so, you can figure how terrifying it was for me as a kid. And after all this years I'm finally writing an article on this damned subject.

The story of Kuru is a haunting reminder of how culture, biology, and mystery intertwine. In a remote corner of the world, a practice born of love unleashed a disease that stumped science for years, reshaped medical knowledge, and eventually faded as quietly as it arrived.

As we delve into the macabre and often misunderstood practices of the past, we must do so with curiosity and compassion—not just for the sake of history, but to better understand ourselves.

Because sometimes, the most terrifying diseases aren't born in labs or spread by mosquitoes. Sometimes, they live in the heart of tradition.

about the kuru disease. it was haunting. it was also my first time learning humans ate humans. so, you can figure how terrifying it was for me as a kid. And after all this years I'm finally writing an article on this damned subject.

About the Creator

E. hasan

An aspiring engineer who once wanted to be a writer .

Comments (1)

This is a wild story. It's crazy how a cultural practice meant to honor the dead ended up causing so much death. I wonder what other cultural practices have had unforeseen consequences like this. And how did they finally figure out the link between the cannibalism and the disease? It's hard to imagine going through something like that. The Fore people must have been so confused and scared as their loved ones got sick. I'm glad we've learned more about these things so we can try to prevent similar tragedies. Do you think there are still cultural practices out there that could be hiding dangerous secrets? It makes you think about how much we don't know about different cultures and their traditions.