The Barber of Alexandria

A Brief History of Ctesibius, the Father of Pneumatics

Ctesibius of Alexandria (285–222 BCE) was one of the first great engineers of the ancient world. A Greek mathematician and inventor, he discovered and experimented with the elasticity of air, earning him the title of the ‘father of pneumatics.’

Although none of his writings survived into the modern age, we know from other references that Ctesibius experimented with and wrote the first studies on how compressed air (and water) can be used to power machines.

Ctesibius has been given credit for inventions that have survived to the present day.

And sometimes he gets credit where credit isn’t due.

The Barber of Alexandria

History remembers very little of Ctesibius’ early life. Third-century Greek author Diogenes Laërtius believed that Ctesibius’ first job was as a barber like his father.

It was during his time cutting hair that he created his first invention and gained his first insights into the elasticity of air.

Ctesibius affixed a mirror to a hollow tube with a lead weight in the opposite end. The lead counterweight allowed the mirror to be adjusted up or down, depending on the customer’s height.

Ctesibius noticed that when the mirror was moved the weight bounced up and down and made a whistling noise. He quickly realized that the noise was air escaping from the hollow tube. This simple invention led him to think about how the power of compressed air (and water) could be used for other purposes.

Credit Where Credit is Due: Improved Water Clocks

Water clocks, or clepsydra (translated as ‘water thief’) were used in courts to measure the amount of time each defendant could speak. Similar to an hourglass, water (instead of sand) was poured into a jar with a hole in the bottom. The water dripped out at a predictable rate. When all of the water had drained from the jar, the defendant’s time had expired.

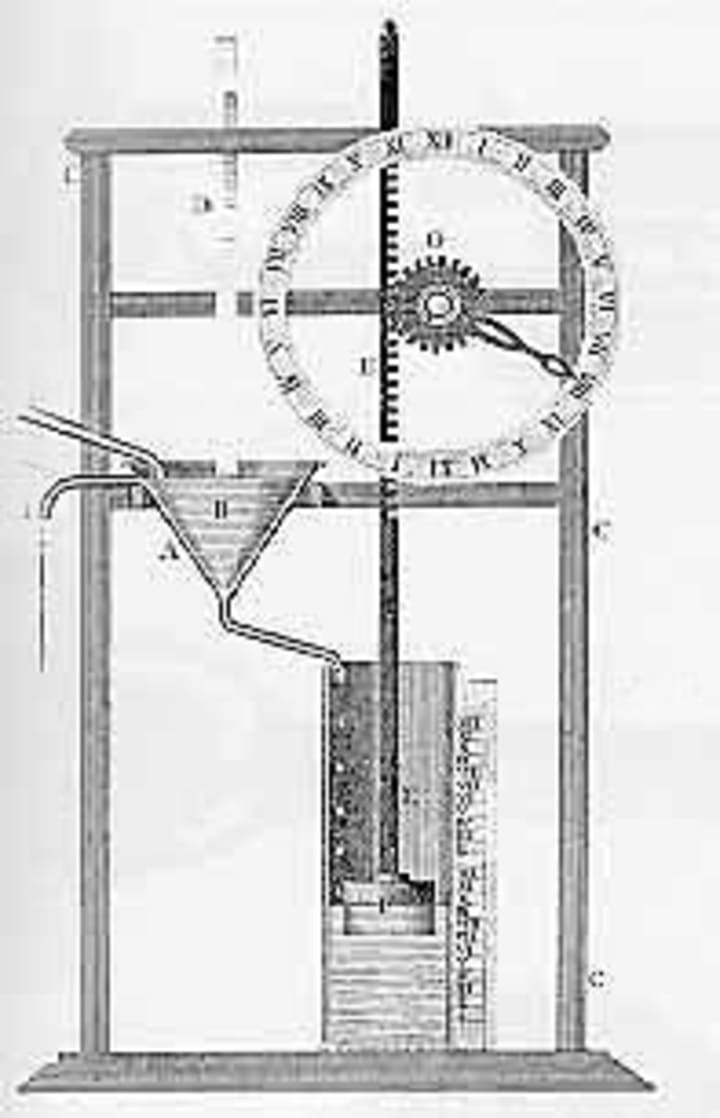

Ctesibius noticed that as the volume of water changed in the jar, it affected the water clock’s accuracy. His solution was to add two more containers — one that kept the water level constant while the other, equipped with a float and a pointer, measured the number of drips.

He also installed the float with a rack to turn a toothed wheel that animated mechanical whistling birds, puppets, and chimes.

For the next 1800 years, Ctesibius’ Water Clock was the most accurate clock in existence, until the Dutch physicist Christiaan Huygens invented the pendulum clock in 1656.

A portion of Ctesibius’ brilliance exists today, for his mechanical birds and chimes still exist in the cuckoo clock.

Credit Where Credit is Due: Water Organs

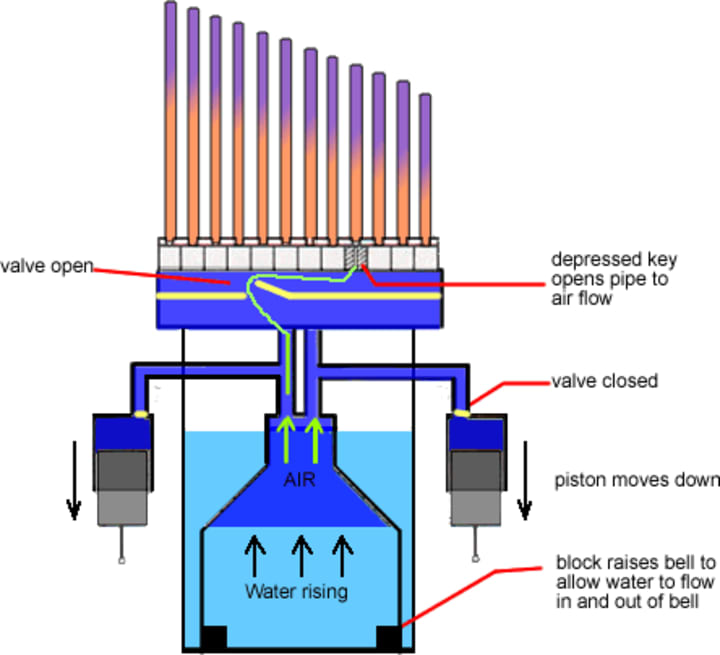

Ctesibius’ hydraulis (or water organ) is the forerunner of the modern pipe organ. Ctesibius’ version forced air through organ pipes by the weight of water rather than falling lead weights.

The water displaced air in a bucket that kept pressure elevated and consistent in the organ even when the pump was on the recovery cycle, giving the organ a continuous sound. Notes could be played by selecting different operating valves.

It was said that he and his wife Thais were very good players.

Credit Where Credit is Not Due: Siphons

Ctesibius is often credited with inventing the siphon, but it is reality much older.

Egyptian hieroglyphics on tombs in Thebes, from the reign of Egyptian Pharaoh Amen-Hotep (approx. 1500 BCE) illustrate wine drinkers siphoning wine from several containers into a large bowl. It is believed that that Egyptians probably used siphons for other purposes such as purifying drinking water.

Hundreds of years later, Assyrian King Sennacherib was building an aqueduct to bring water to the city of Nineveh. To get over a hill that stood in the way, he had constructed a large siphon to move the water over the hill. This ancient siphon was so efficient that modern engineers could not improve on this design until the 19th century.

Modern scientists today are divided on how siphons work.

Some believe they work due to the difference in the atmospheric pressure between the high and low points in the tube. This theory was discredited when a siphon was tested in a vacuum found that siphons still worked.

Others believe that when a liquid is sucked over the hump of a siphon gravity pulls the liquid along the tube.

Still others contend that small bonds between molecules pull the other liquids up and through the tube.

No matter who is correct, one this is certain — siphons were around a long time before Ctesibius.

Conclusion

Ctesibius would rise from humble beginnings to become the head librarian of the Library of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Ctesibius established the foundations for an engineering tradition that has given us the knowledge to develop compressed air that is used in various modern machinery such as drills, presses, paint sprayers, and high-pressure water cleaners.

Not bad for a humble barber.

About the Creator

Randall G Griffin

I am Pop-Pop, dad, husband, coffee-addict, and for 25 years a technical writer. My goal is to write something that somebody would want to read.

Comments (1)

This article earns my appreciation for being both well-written and informative.