One of America's Oldest Missing Teens Case: Bonita Bickwit & Mitchel Weiser

In 1973, two teens in love set out hitchhiking to a rock concert and were never heard from again...

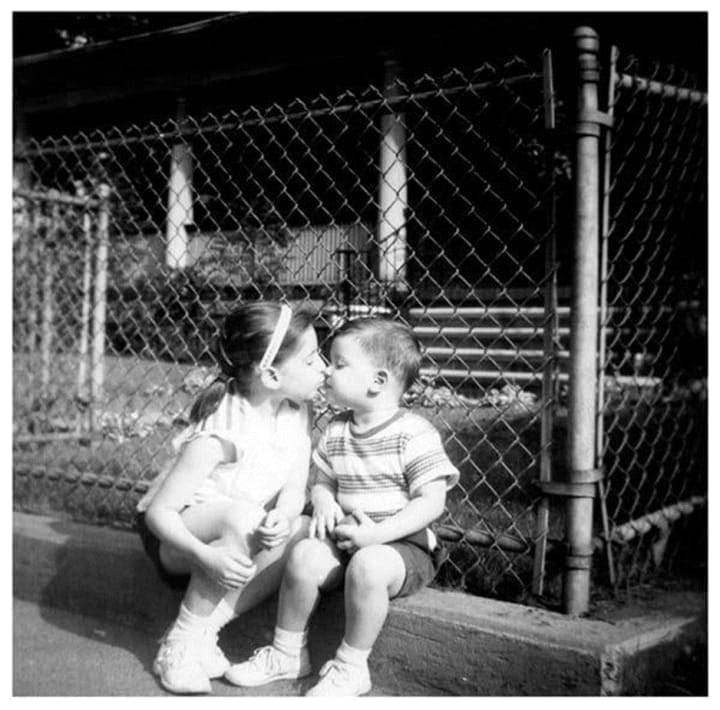

Young & in love, 16 year old Mitchel Fred Weiser and his girlfriend of one year, 15 year old Bonita Mara Bickwit - or 'Bonnie' to her friends and family, were a teenage couple in the summer of 1973.

The teens had first met at Brooklyn's John Dewey High School, a school for gifted students, when their respective friend groups merged into one circle. From there, Bonnie and Mitch quickly grew very close.

Both came from loving Jewish families and lived in well-to-do neighbourhoods in New York—Bonnie’s family in Borough Park and Mitchell’s in Midwood.

Despite their young ages, they were deeply devoted to one another, even exchanging wedding rings in secret that year. Friends often recalled how they would refer to each other as husband and wife, a testament to the intensity of their bond.

In June of that year, with school out for the summer, Bonnie and Mitchell had gone their separate ways for work. Mitchell was working as a photographer’s assistant at the Chelsea Booth on Coney Island, while Bonnie was 120 miles away in Narrowsburg at Camp Wel Met, working as a mother’s helper.

But being kids of the ’70s, they were both eager to experience the most talked-about event of the season: Summer Jam.

Summer Jam was one of the biggest music festivals of its time, drawing over 600,000 attendees and even earning a Guinness World Record for the largest audience at a music festival. Fans flocked to see some of the era’s most popular bands, including the Allman Brothers and the Grateful Dead. Everyone wanted to be part of this iconic event.

Mitchell had tickets to attend, but he was planning to go with his friend Larry. Just a few days before the festival, however, Larry’s mother had a bad feeling and forbade him from going, leaving Mitchell to reconsider his plans.

With Larry unable to go, Mitchell was left with a spare ticket and urged Bonnie to join him. At the time, she was working for a family in Narrowsburg. She asked her employer for a couple of nights off to attend the festival, but when her request was denied, she became frustrated and quit on the spot.

Bonnie informed her employer that she was leaving but would return later to collect her pay check. Her mother later explained that Bonnie felt exploited—she had been working 16-hour days and constantly clashing with the family. In her eyes, if she couldn’t have a few days off to enjoy her summer, she didn’t want to work for them anymore.

The only problem was getting to Summer Jam. The festival was being held in Watkins Glen, roughly 75 miles away, and the teens had no transportation. Their only option was to hitchhike.

In the 1970s, an era that celebrated freedom and adventure, hitchhiking was seen as a relatively safe and practical way to get around—especially for young people with little money and no means of transportation who were determined to travel.

When Mitchell’s mother learned that he was no longer going with his friend and planned to hitchhike to the festival, she had a very bad feeling and pleaded with him not to go. His sister Susan, however, described him as extremely stubborn—there was no way he was going to miss the event.

A few days before the concert, Mitchell found himself enduring yet another lecture from his mother. Eventually, she realised he was determined to go regardless. As she turned to fetch her purse to give him some money for transportation, Mitchell bolted out of the house.

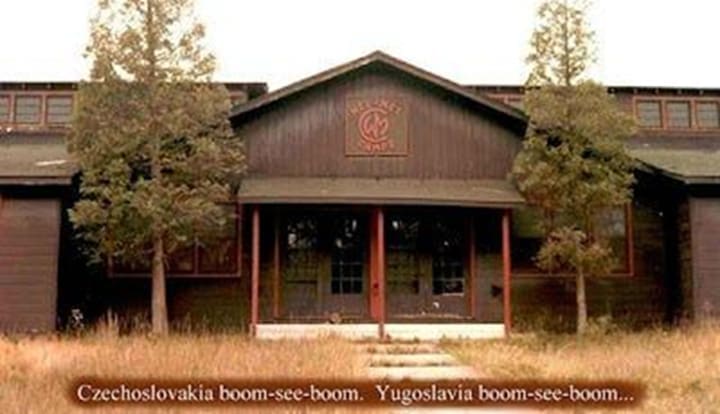

Mitchell boarded a bus to Narrowsburg, where he was to meet Bonnie at Camp Wel Met. From there, they planned to travel together to Watkins Glen for the festival. According to his sister Susan, he had only $25 in his pocket when he set off on the 120-mile journey, arriving at Bonnie’s camp around midnight. It was then that he called her to explain he had already spent all his money on the bus ride.

Susan was understandably anxious and warned him that if he didn’t have the funds, he shouldn’t attempt to go to the festival. But Mitchell refused to listen. Before hanging up, he reassured Susan that he would be home by Sunday night. Tragically, this would be the last time his family ever heard from him.

In the week leading up to the festival, Bonnie had been seen sneaking into her home by neighbours—apparently to collect the $80 she had saved to buy a new bicycle.

Finally, the day of the festival arrived: Saturday July 28th 1973. Bonnie and Mitchell were spotted leaving the camp by friends. Bonnie wore a peasant blouse, a bandanna, and blue jeans, while Mitchell sported his trademark slicked-back ponytail, a T-shirt, jeans, and boots. They carried a backpack, a sleeping bag Bonnie had borrowed from a friend, and a cardboard sign she had made that read, “To Watkins Glen.” The pair were last seen walking along State Route 97, hoping to hitch a ride to the festival.

By Sunday night, Mitchell’s family stayed up anxiously, waiting for him to return as planned—but he never walked through the door. Bonnie’s parents, who had been on vacation in Cape Cod, returned home a few days later on Tuesday, only to receive a phone call asking if Bonnie had arrived. Confused, they assumed she was still at camp.

It was then that Mitchell’s family revealed she had quit her job days earlier and left to attend the festival with Mitchell. Since then, however, no one had seen or heard from either of them.

Bonnie’s family immediately went to her summer camp in Narrowsburg, but when they found that neither teen was there and no one had heard from them, they contacted the local authorities to report them missing.

Initially, the police did not take the case seriously. They assumed Bonnie and Mitchell had simply run away together, viewing them as two young teens in love—a scenario that was becoming increasingly common in the 1970s. With many young people questioning societal norms and seeking freedom, officials expected the pair would eventually turn up on their own.

Adding weight to this theory, Bonnie’s parents found a letter she had written just three days before leaving for the festival. In it, she expressed her desire for independence and to enjoy her summer if only her parents would trust her with more responsibility.

After reading the letter, Bonnie’s mother understood her daughter’s yearning for freedom, but the mysterious circumstances of their disappearance left her uneasy. She couldn’t shake the feeling that there was more to Bonnie and Mitchell vanishing than a simple runaway adventure.

Friends and family of both Bonnie and Mitchell noted that, in the weeks before they vanished, the pair seemed uneasy. Bonnie was struggling with the family she worked for, and on top of that, her beloved father was seriously ill. These worries weighed heavily on her, and she was often brought to tears.

Mitchell, meanwhile, was anxious about his future: he feared he wouldn’t be able to attend the prestigious college of his choice because his parents couldn’t afford it, forcing him to consider a school closer to home—a prospect he deeply disliked.

Despite these challenges, neither family believed that Bonnie or Mitchell would run away. These were typical adolescent struggles—difficult and emotional, but not the kind that would drive them to abandon the families they loved so dearly.

Mitchell had been looking forward to his driving test, which was scheduled just a few days after his disappearance. Meanwhile, Bonnie had been corresponding with a friend throughout the summer. Her friend noted that Bonnie seemed completely in character and had never mentioned anything alarming—no plans to run away or hints of trouble.

Since July 27th 1973, the pair were never seen or heard from again. Their families have never forgotten them. Bonnie’s mother remained in the same house for decades, hoping her daughter would one day return. Mitchell’s family eventually moved to Arizona but kept a phone listing in the Brooklyn directory since 1973, in case Bonnie or Mitchell tried to make contact.

Thirteen years later, Mitchell’s father received a collect call from someone identifying herself as “Bonnie.” He was ecstatic, and according to him, his excitement could be heard over the phone. Tragically, before the operator could connect them, the caller hung up. His father blamed himself, fearing he had scared her away. The caller never called back and has never been identified.

The case lay dormant until 1998. On the 25th anniversary of the festival, reporter Eric Greenburg—who had remembered Bonnie and Mitchell’s story—began his own investigation. What he uncovered was deeply disturbing.

The Sullivan County Sheriff’s Department, responsible for the case, admitted that they had lost the original files, including investigatory notes taken at the time. The only remaining copies of Bonnie and Mitchell’s dental records, which could have helped identify their remains, had also been destroyed by mistake. Furthermore, the department admitted to failing to interview key people connected to the case, including the teens’ friends, family, and staff at the summer camp.

In 2005, the only credible lead in the case would surface when a witness named Allyn Smith came forward. Smith said that in 1973, at age 24, he had been hitchhiking to the Summer Jam festival. As he walked along the road, a VW camper van pulled up and offered him a ride.

Smith accepted the ride and climbed into the back of the van, where he said he encountered a young teenage couple who matched the descriptions of Bonnie and Mitchell. He told police that he overheard them talking about the girl’s summer camp.

According to Smith, the group stopped along the way to cool off in a river. The long drive had left everyone hot and uncomfortable, so they wanted to splash some water on themselves. Smith claimed that the girl got into trouble in the water and began screaming for help. The boy jumped in to save her, but both were reportedly swept away by the current, still alive and crying out for assistance.

The driver of the Volkswagen allegedly told Smith that he would call the police from the nearest gas station. However, authorities have no record of any such call being made.

While police considered Smith credible, questions arose about why, as an athletic Navy veteran, he did not attempt to rescue the teens. Smith explained that the current was too strong and he could do nothing to help.

Investigators looked into Smith’s account, but there was no way to verify his story. He could not remember the location of the river, and the Volkswagen driver has never been identified. Attempts to locate the river where the group allegedly stopped proved unsuccessful.

During the summer of 1973, New York experienced a scorching heatwave and a severe drought. Water levels in rivers and streams were significantly lower than usual—experts estimate no more than five feet deep. Even though Bonnie was only 4’11”, the current at the time would not have been strong enough to sweep two teenagers away. Moreover, if they had truly been carried off as Allyn Smith claimed, their bodies likely would have surfaced at some point.

Many have questioned Smith’s account, suggesting that the camper van may have never existed. Some speculate that he may have encountered the couple during his travels and perhaps harmed them, while crafting a story that hints at their fate without directly implicating himself.

As of 2025, Bonnie and Mitchell remain missing, and their case remains unsolved. If alive today, Mitchell would be 68 years old and Bonnie 67. Age-progression photographs have been created to show what they might look like today.

About the Creator

Matesanz

I write about history, true crime and strange phenomenon from around the world, subscribe for updates! I post daily.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.