Nigeria’s Ancient Kingdoms

Part 2: The Stateless Society of the Igbo and the Rise of Hausa Kingdoms

Picture a society that flourishes without centralized political entities. This fascinating concept is not an outcome of modern socio-political experiments but has its roots buried deep within the rich history of the Igbo society.

A cluster of brilliant minds propounds that prior to the intrusion of colonial rule, the Igbo society was a stateless entity flourishing in its unique autonomous glory. In this intriguing realm, the Igbo, known for the balanced societal structure, thrived in self-sufficient clusters of villages. Lineage was the bedrock of their societal organization, acting as an ironclad shield against the incursion of social stratification. A person’s fitness to govern didn’t rely on birthright, riches, or strength but rather on the wisdom that was wrought through the crucible of age and experience.

In the midst of this harmonious communal life, yams ruled the roost, and subsistence farming reigned supreme. Land, the source of this life-giving crop, was a tangible symbol of wealth gained not through conquest but through the more peaceful process of inheritance. Complementing their farming prowess with their well-honed skills in handicrafts and commerce, creating a dynamic local economy that flourished amidst a bustling population.

In the absence of traditional chieftaincy, certain Igbo communities relied on an innovative system of priestly order. These priests hailed from the outskirts of Igboland and were believed to be the impartial adjudicators, settling community disputes with divine wisdom. Their pantheon, reminiscent of the Yorubas, teamed with deities that maintained a beautiful symmetry with humanity, echoing the egalitarian essence of the Igbo society itself. Among the multitude of gods, the central figure was Ala, the Earth Mother, a symbol of fertility whose shrines dotted the expanse of Igboland.

The puzzle surrounding the statelessness of the Igbo society, however, remains incomplete. This theory stumbles upon the lack of historical evidence painting a vivid picture of the pre-colonial Igbo world. The gap between the archaeological treasures of Igbo Ukwu, exhibiting a thriving culture around the 8th century A.D., and the 20th-century oral narratives is vast and mysterious.

Notably, the importance of the Nri kingdom is often lost in the annals of history. Though geographically compact, it carries the weighty legacy of being the cradle of Igbo culture. Furthermore, the influence of the Benin kingdom on the western Igbo presents a complex layer to this narrative as they incorporated political structures akin to the Yoruba Benin region. This jigsaw puzzle of history awaits to be deciphered piece by piece, illuminating the full scope of the Igbo societal structure and culture.

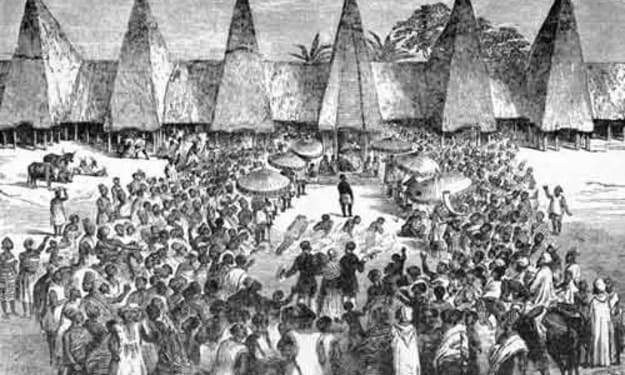

In the third millennium B.C., as the Sahara Desert slowly extended its grip, the early inhabitants adapted, scattering into the vast savanna landscapes. This geographical shift, in turn, gave birth to the trans-Saharan trade routes, establishing a link between the Western Sudan and the Mediterranean, a link that remained active until the end of the 19th century.

These same routes allowed the potent influence of Islam to seep into West Africa after the 9th century A.D. By then, a series of dynamic states, including the initial Hausa kingdoms, unfolded across the Western and Central Sudan. Among them, Ghana, Gao, and Kanem were the titans, though not located within modern Nigeria’s borders. These states profoundly influenced Nigeria’s savanna history, indirectly imprinting the cultural and economic footprint.

Even as these Western empires lacked a significant political influence on the Nigerian savanna states before 1500, the cultural and economic imprints were evident and amplified in the 16th century, particularly due to their association with Islam and trade. The history of Borno intertwines closely with Kanem, which by the 13th century had risen to imperial status in the Lake Chad basin, governed by the Sefawa dynasty, descendants of pastoralists who settled around Lake Chad in the 7th century. The king, or Mai, of Kanem ruled as a constitutional monarch in consultation with the council of peers.

As with the Western empires, Islam became an essential part of Kanem-Borno's identity. By the late 11th century, Muslim Berbers and Arabs began to settle in Kanem. With the conversion of Mai Umme to Islam around 1085, Islamic practices took root within the Kanem royal court. Over time, Islam seeped into the Borno society through trade links with Egypt and North Africa. The state engaged in trade exchanges of slaves, natron, salt, and grains, fortifying the kingdom’s prosperity.

While the political landscape of Kanem faced frequent upheavals due to dynastic discord, the essence of Kanem-Borno endured through centuries. By the late 14th century, Borno declared independence from Kanem and established the Sayfawa dynasty, evolving into a formidable force that navigated the harsh terrain of dynastic conflicts and trade ambitions, leaving a legacy etched in the annals of Nigerian history.

About the Creator

Balovic

Though I might be late, I never fail to make progress.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.