Being obsessed with all things “Edwardian”, I couldn’t start reading this book fast enough. To read the actual ‘voices’ of children and adults who lived in the Edwardian Era just caught my attention. It was a real eye opener because these people lived in such different times, and although the Edwardian Era was the past moving into the modern, the lives and lifestyles of these ones was still a world away from the way we live today in 2025.

It’s better if I let these children and adults speak for themselves, so I have picked out a few of these ‘Lost Voices’ so that they can speak for themselves.

Childhood =>

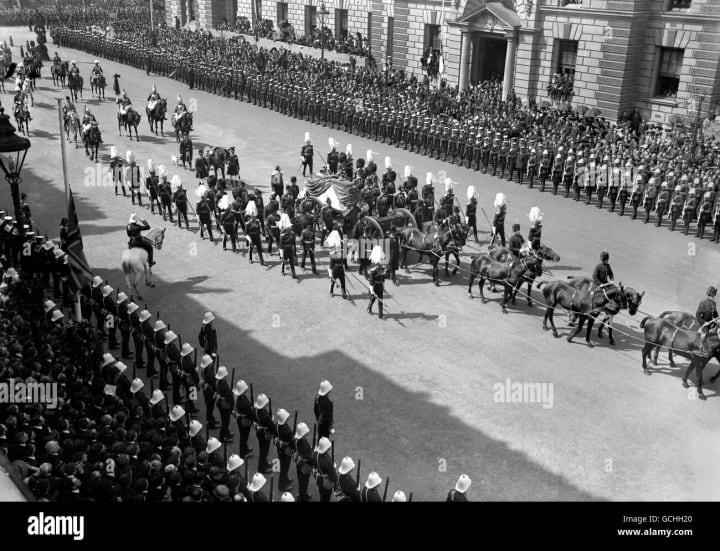

Kitty Marion: “On 22nd January, 1901, the manager of the Opera House, Cheltenham, announced to the audience the news of Queen Victoria’s death. People listened and quietly dispersed. It seemed as if the world stood still and could never continue without the Queen. However, the following day King Edward VII was proclaimed King and life went on as usual.”

Bob Rogers: “My mother had sixteen children. She had diseased kidneys from too many births. Only me and one sister grew up. My mother had so many miscarriages. In the end, it killed her. She died at the age of forty-six.”

Fred Lloyd: “I was born on 23rd February, 1898, at Copewood in Uckfield. There were sixteen of us in our family — I had eight sisters and seven brothers. My parents really loved children. My mother died when she was forty-three — I learned from one of my sisters that she died in childbirth. My father died soon after and they said it was from a broken heart.”

Jack Banfield: “In my family, there were seven children as well as Mum and Dad. Two of the children died as babies. That was very common. When you got over the age of about ten, you were past the post. Until then, there was measles, whooping cough, chicken pox, scarlet fever, and so many diseases.”

Jack Brahms: “I was twelve when my mother died and after I had to fathom for myself. Father couldn’t do much for me. He used to make me go to the synagogue every morning and evening but apart from that he wasn’t interested. He might have made a meal at the weekend but most of my meals were a ha’p’orth of chips from Phillips, the fish and chip shop in Brick Lane. I’d sit on my doorstep and eat it. Or else, I’d go to the soup kitchen to get a can of soup and a loaf of bread. I used to go to McCarthy’s lodging house because they had a fire burning there and I’d have a warm up. I had to bring myself up.”

Work =>

George Wray: “My father died when I was thirteen and my mother decided I should be looking out for a job. I asked her to speak to an uncle who worked at a colliery. I wanted to go down the pit for one shift with him to see what it was like. Even in those days, people who weren’t connected with the mines thought that it was a bit out of the order of things to want to do that. No one wanted to go down the mine when they left school. However, I went down for a shift with my uncle and I decided I wanted to work down the pit.”

George Cole: “I left school when I turned fourteen. I left at teatime, had a drink of tea with my dad, walked up to Seaham Colliery, signed on and started work the next morning. I was down the pit at ten minutes to five on the day after I finished school.”

Albert ‘Smiler’ Marshall: “If you were an apprentice, or you had a job to go to, you could leave school at thirteen, but if not, you had to stay until you were fourteen. After that, you had to leave whether you had a job or not. I was apprenticed to the nearest shipyard, so I left school at thirteen. I changed from knickerbockers to trousers. At the shipyard, I was working with a Yorkshireman who was making all these beautiful doors. All I was doing was handing him the screwdrivers and saws and different tools while he was doing the work. In other words, I was a first-class-carpenter’s labourer. At the end of my first week’s work, I got two shillings and fourpence and felt quite rich.”

Mrs Brown: “When I was twenty I left to be a nurse. I started at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle, which was a new hospital in 1907. I was there until my feet let me down, I had terribly blistered feet. I worked sixty-five hours a week and I got no wages for three months. I had nothing except my keep, as I lived in. At night I used to be so tired I used to scream when I put my feet on the bed. It was exceptionally strict. You were never allowed to start a conversation, you were never allowed to speak unless you were spoken to, and you were never allowed to walk in front of a senior. You had to do exactly what you were told — you could never answer back. You had no social life at all. I remember saying to a sister that I had an appointment with my young man, and she said, ‘Nurses in training have no business to make appointments.’ I wasn’t allowed to go.”

Home =>

Mary Keen: “I worked for Mrs Johnson in a big Victorian house with long flights of steps. I cleaned the steps with the hearth-stone and I did the brass, dusted the front door, cleaned the area and the bits around it, and then swept the hall. I worked from eight in the morning until eight at night and on Sunday from eight until four, and I was paid two shillings a week. Working conditions were very bad. Mrs Johnson never so much as offered me a cup of tea. I had my midday dinner and tea, but I didn’t get enough to eat because she was a very mean type of woman. I didn’t like her. I’d been with Mrs Johnsom for nearly a year when my mother said to me, ‘Tell her you won’t be coming anymore. You’ll be leaving her next week because I’m going to have a baby.’ Mrs Johnson didn’t like that very much, but I was glad. I went home on the next Saturday and the baby had already arrived — a little fair-haired, blue-eyed girl. She was a dear little thing. My mother was in bed for just over a week and I took charge of her.”

Daily Life =>

Mildred Ransom: “London had space and time in those days to appreciate characteristic happenings. There was an old woman in St.James’s Park, close to the Horse Guards, who kept a cow, and sold cow’s milk, cakes and sweets to passers by. She had a tiny hut, but I do not think she lived there. She was one of the sights of London. Another sight was Mr Leopold de Rothschild driving his tandem of zebras in the Park. We used to admire, but not touch, the famous Piccadilly goat; we bowed as the old Queen, now deeply beloved, drove slowly by, or the Princess of Wales passed with her three daughters packed into the back seat of a landau. Royalty passed with a stately step then.”

John William Dorgan: “In 1900 I was going to school and my parents were very, very poor. I know poverty right to its limit. I was brought up on rice pudding and broth. Those were the cheapest meals anyone in our position could get. I can’t remember ever having any meat in my schooldays. My mother made all our clothes. She’d go to a jumble sale or a second-hand shop and buy an old suit and take it apart until it was just cloth, and then she would make me something.”

Travels and Excursions =>

Mary Keen: “Everything was dirty. The transport, the streets, everything. They hardly ever cleaned the trains, so you had to be very careful with your clothes. You generally took a bit of rag or something to rub the seat where you were going to sit.”

Ray Head: “The streets of the City of London were very, very dirty. The horse manure was all over the place. Boys used to collect it up in little pans and brushes and put it in special containers. At night time, the cleaners used to come along with hoses and hose the whole City.”

Ronal Chamberlain: “I remember seeing the first motorbus. It must have been in about 1907. Somebody shouted ‘Quick! Quick! Come and Look! There’s a bus without a horse!’ It was a very primitive thing running along in Islington, making an awful lot of stink and noise, but everybody stood up to look.”

Mary Keen: “I remember the first motor cars. They used to have a man with a red flag walking in front. Everyone was very excited at seeing them. They were open, with two people sitting at the back, and people used to walk and run behind them.”

Eveline Goddard: “As I grew older, we took to a car, which my father hated like poison. He considered it an invention of the devil! Anyway, he never drove himself, but as soon as I could drive — and I could drive quite well — I used to drive him around. The hay trade in which he had worked all his life was finished more or less, because cars were coming, so hay wasn’t needed for the horses.”

Politics And Suffragettes =>

Kitty Marion: “One of the first things I learned was to sell the paper “Votes for Women”, on the street. That was the ‘acid’ test. The first time I took my place on the island in Piccadilly Circus, I felt as if every eye that looked at me was a dagger piercing me. However, that feeling wore off and I developed into quite a champion paper-seller.”

Mary Keen: “I thought the suffragettes were right. They were women paying rates and taxes but with no say as to who was in Parliament. Yet an ordinary man, uneducated, ignorant, he wouldn’t know what he was voting for but ‘he’ could have a vote.”

Katherine Willoughby Marshall: “No one hearing Emmeline Pankhurst’s lovely voice could be unmoved by what she said. It was so clear that when in the Albert Hall, she never used a microphone. Her eloquence was remarkable and she talked so much common sense that it was no wonder that she had a great following of supporters. I never heard her say one word against anybody. If we abused Mr Asquith, she would wave her hand, as if dismissing him from her mind. She was a wonderful leader and a friend.”

Military =>

Don Murray: “I remember the of the Boer War. We were allowed to go out in the playground, line the railings round the school, and we all had little Union Jacks as the soldiers were marching back from the Boer War to the barracks at the top of the road. I remember one soldier in particular had a bandage round his head and we cheered madly at him. We thought he was a hero.”

George Finch: “Our day started at seven o’clock. We would exercise on the parade ground, then at eight we’d have breakfast. After that we’d go down to the cliffs to a place called the Drummer’s Pit, where we’d exercise on the bugle, fife and drum.”

Thomas Painting: “I left school at eleven and a half, and went to work for W.H.Smith and Sons at Lichfield Trent Valley Station. My father was a ganger on the railway. During this time the Boer War was on, and I was fired with what the Army did — and not only that — I could read a magazine like “Wide World” and the “Royal” along with the “Sheffield Weekly Telegraph”. I was only fourteen and a half, but I wanted some of the excitement. With me reading all these adventure books, I thought, ‘Well, I’d like to join the Army and see the world’. I left the bookstall and went on the railway as a cartboy at Birmingham New Street and then I finished up at Coventry. I made my decision. I said to Mother, ‘I’m going for a ride this morning, Mum’. Off I went to the Warwick Depot and enlisted.”

End of an Era =>

Louis Dore: “I can recall that on that day that Edward VII died, people walked about with sad looks on their faces, talked only in whispers, and the respectable wore their mourning attire. This may sound like an extravagance for people who lived in one of the worst slums in north-east London — the place where I was born — but the truth is, no one with any sense of pride would have been without mourning clothes. That evening the men and many of the women retired quietly to their local in order to console themselves. The King was dead. It was almost as if God himself had died.”

Conclusion =>

There are 434 pages in this book with hundreds of experiences, so as you can imagine, I spent time ‘choosing’ which experiences to put into this article, (which I thoroughly enjoyed).

What I was aiming at was to show the difference in ‘worlds’ between the Edwardian Era and today 2025. Children doing half days at school and half days at work, and some leaving at 13 years of age ‘if’ they had a job. Even the ‘jobs’ were completely different, with much longer hours with very little pay. Then the motor car taking over from the horse and cart, and even the experience on the ‘dirty’ trains. All of this whilst wearing very different clothes too.

I’ve decided to do an article on each chapter, going into much more detail. I hope you find these articles as interesting as I will do researching and writing them.

Thank you for reading this long, but hopefully interesting, article on the Edwardian Era and the Lost Voices.

About the Creator

Ruth Elizabeth Stiff

I love all things Earthy and Self-Help

History is one of my favourite subjects and I love to write short fiction

Research is so interesting for me too

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.