How the Genius of Marie Curie Killed Her

How the Genius of Marie Curie Killed Her

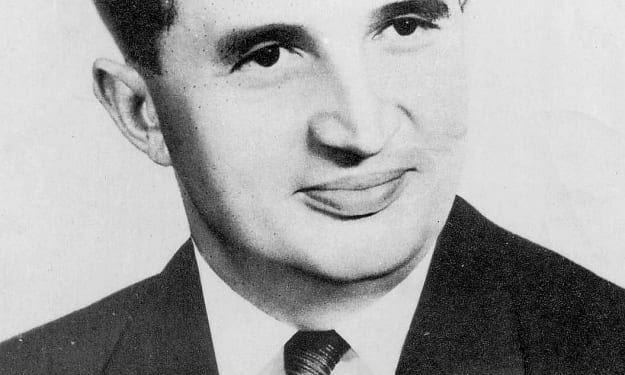

In 1927, 29 of the world's leading physicists gathered at the prestigious Solvay Conference in Brussels. The sole female attendee was Marie Curie, a pioneering scientist with numerous groundbreaking achievements. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person to win the Nobel Prize twice, and the first to win in two different fields. Curie's work on radioactivity would save countless lives during World War I, though it ultimately contributed to her own demise.

Curie, born Maria Salomea Skłodowska in Warsaw, Poland, was the youngest child of teachers. Her mother was the headmistress of a prestigious girls' boarding school, while her father taught physics and mathematics. Despite their family's financial struggles, the Skłodowskis instilled in Maria a deep love of learning. However, as a woman, Maria was barred from attending university, so she and her sister Bronisława enrolled in the clandestine "Floating University" in Warsaw.

In 1891, at the age of 24, Maria arrived in Paris, where she enrolled at the Sorbonne and earned degrees in physics and mathematics. There, she met and married the renowned physicist Pierre Curie. Together, they made groundbreaking discoveries, including the elements polonium and radium. Their work on radiation earned them the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics, shared with Henri Becquerel.

Tragedy struck in 1906 when Pierre was killed in a freak accident. Marie was offered his academic position at the Sorbonne, becoming the first female professor in France. She went on to win a second Nobel Prize in 1911, this time in chemistry, for her continued research on radioactivity. However, her personal life came under intense public scrutiny due to an affair with a married man.

During World War I, Curie's expertise in radioactivity proved invaluable. She developed mobile x-ray units, called "little Curies," that helped locate shrapnel and bullets in wounded soldiers, saving an estimated one million lives. Yet this selfless work likely contributed to the health issues that would ultimately claim her life.

Curie continued her groundbreaking research in the later years of her life, founding the Radium Institute in Paris and another in Warsaw. She died in 1934 at the age of 66, from aplastic anemia likely caused by radiation exposure. Curie's remains are still radioactive, and she was the first woman to be honored in the Panthéon in Paris on her own merits.

Curie's tireless work and unwavering determination in the face of immense personal and professional obstacles cemented her status as one of the greatest scientists of all time. Her legacy continues to inspire generations of researchers and innovators.

Summary:

In 1927, Marie Curie, a pioneering scientist, attended the Solvay Conference in Brussels, where she was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person to win the Nobel Prize twice, and the first to win in two different fields. Born Maria Salomea Skłodowska in Warsaw, Poland, she was the youngest child of teachers and was barred from attending university. She enrolled in the clandestine "Floating University" in Warsaw and later enrolled at the Sorbonne in Paris.

Maria married physicist Pierre Curie, who made groundbreaking discoveries, including the elements polonium and radium. Their work on radiation earned them the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics, shared with Henri Becquerel. Tragically, Pierre was killed in a freak accident in 1906, and Marie was offered his academic position at the Sorbonne. She won a second Nobel Prize in 1911, this time in chemistry, for her continued research on radioactivity.

During World War I, Curie's expertise in radioactivity proved invaluable, developing mobile x-ray units called "little Curies" that helped locate shrapnel and bullets in wounded soldiers, saving an estimated one million lives. However, her selfless work likely contributed to her own death.

Curie continued her groundbreaking research in later years, founding the Radium Institute in Paris and another in Warsaw. She died in 1934 at the age of 66, likely due to aplastic anemia caused by radiation exposure. Her remains are still radioactive, and she was the first woman to be honored in the Panthéon in Paris on her own merits.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.