Between a (Banaban) Rock and a Hard Place

Where Do the Banbans Go from Here?

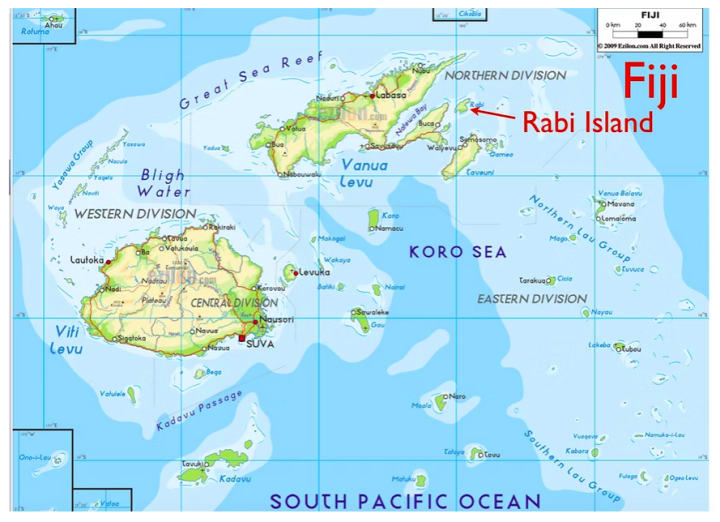

What began as a friendly inter-island rugby game between Banaban and Fijian youths in the early 1980s unexpectedly turned sour, forcing the peace-loving Banabans to confront the precarious nature of life on their new island home, Rabi. As Banaban elders instructed women and children to remain behind locked doors, boatloads of Fijian youths arrived, seeking to settle scores from matches held earlier that day.

What started as a sporting rivalry escalated into what the Banabans perceived as a small-scale invasion, highlighting their status as a minority on Rabi and their vulnerability to their Fijian neighbours. The incident instilled fear in the younger generation. At the same time, Banaban elders were painfully reminded of the invasions and torture they had endured over thirty years earlier when Japanese forces occupied their homeland, Banaba (formerly Ocean Island), during the Pacific War.

Since then, other incursions have followed—ranging from breaches of local laws by Fijian fishermen to rumors of Fijian chiefs questioning how the Banabans came to live on one of Fiji’s best islands. While these events have been more low-key, they have nonetheless caused alarm, particularly among Banaban elders who have seen such threats before. They had suffered under Japanese occupation, witnessing their people tortured and killed, but perhaps even more devastating was their long, futile struggle for the survival of their homeland—Banaba.

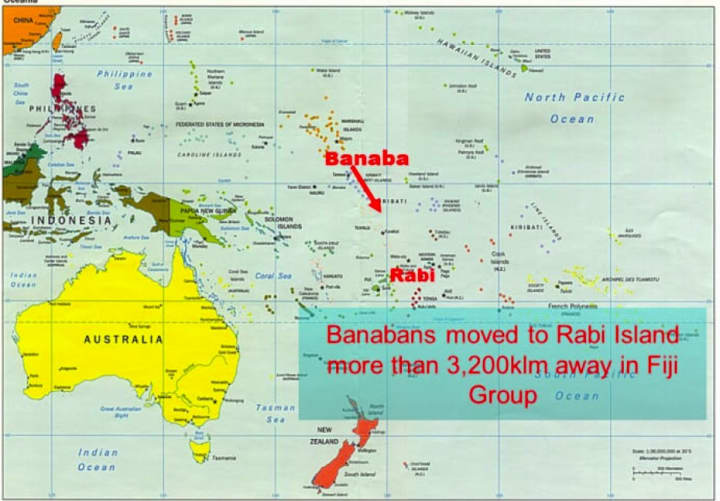

When phosphate was discovered on Banaba in August 1900, the island—once dismissed as “no man’s land” in the Pacific—became one of the wealthiest in the region. But for the Banabans, this discovery marked the beginning of a long and painful struggle for justice that continues today. They remain steadfast in their belief in their right to exist as Banabans and to uphold their cultural identity and connection to their homeland. Yet, their tenure on Rabi may be about to change.

The headline “Fijians Want Their Island Back” (Fiji Times, 4 June 2007) was one of several unsettling reports in Fiji’s press, subsequently echoed in other Pacific media. The issue, now public, came to a head while Fiji remained under military rule. Young Banabans were shocked by the looming uncertainty of their future, but their elders recognised that their worst fears were becoming reality. For decades, these elders had shared stories of past struggles, and younger Banabans believed they were insulated from such hardships. Their focus had been on immediate survival, particularly following the devastation caused by multiple cyclones over the years. International aid took years to reach Rabi, while Banaban frustrations mounted over the island's lack of development and infrastructure.

Banaba, their ancestral homeland, has been devastated by eight decades of phosphate mining, yet it remains the heart of Banaban identity. For over a century, Banaba enriched the governments and farmers of the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, while Banabans themselves were left impoverished and politically marginalised. Although their future had seemed tied to their existence on Rabi, recent events have shown that their relocation to a freehold island within Fiji’s territory is anything but secure.

As the realisation dawns that Rabi is home to more than one displaced people, the questions of development and progress grow ever more complex.

Australia’s Role in the Mining of Banaba

An Australian Connection to Banaba’s Past

Australian Stacey King, a descendant of three generations of the Williams family—phosphate pioneers on Banaba—acknowledges Australia’s deep involvement in the island’s environmental destruction. While Australia prospered from Banaba’s phosphate, the Banaban people bore the tragic cost: the loss of their homeland.

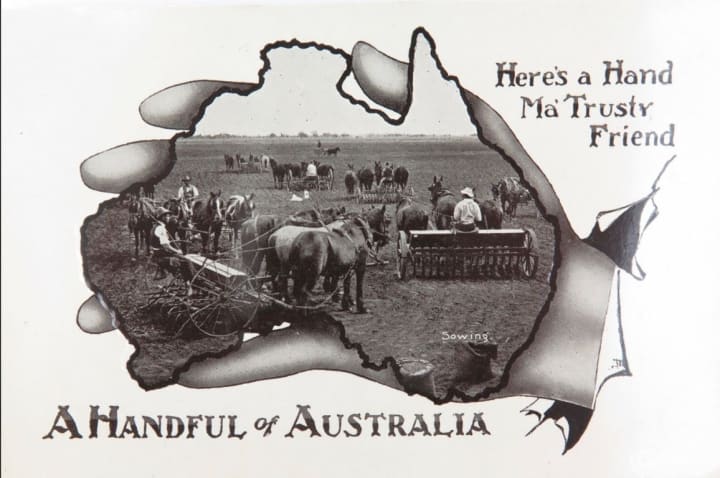

Understanding Australia’s role in Banaban history requires revisiting a crucial period when the country emerged from British colonial rule. During this time, Banaba’s phosphate became essential to Australia’s agricultural and economic development, fueling progress while leaving the Banaban people displaced and their island devastated.

A New Nation Built on Banaban Phosphate

Between 1855 and 1890, Australia's six colonies gained responsible government while still remaining under British sovereignty. By 1901, the Federation united these colonies, creating the Commonwealth of Australia—a nation eager to embrace progressive values, human rights, and democratic procedures. Yet, this period also saw the introduction of racially restrictive policies, including the White Australia Policy (1901–1973), which severely limited non-European immigration.

Australia’s agricultural sector flourished during this time. Wool production became the backbone of the economy, and Australian farms expanded rapidly. The newfound success depended heavily on superphosphate fertilisers, derived from Banaba’s rich phosphate rock deposits. The 1900 discovery of phosphate on Banaba revolutionised Australia’s farming industry, fueling exports and economic growth.

Australia–Banaba Relations Today

Despite Banaba’s pivotal role in Australia’s prosperity, the Banabans remain politically isolated, with no official recognition from Australia. They are denied access to the country that benefited most from the destruction of their island.

King questions why the Banabans, unlike their Pacific neighbour Nauru, were left politically marginalised despite sharing a similar phosphate-mining history under Australian involvement. Before Kiribati gained independence in 1979, Banaba was under British control, while Nauru received formal recognition from Australia. However, Australia claimed one-third ownership of Banaba’s phosphate reserves, reaping financial rewards without ever accepting responsibility for the devastation left behind.

The Banabans paid a price—over 20 million tons of Banaba’s soil, including the remains of their ancestors, were shipped away, with 13 million tons scattered across Australian farmland. The near-total destruction of Banaba’s environment and its population of just 450 people was dismissed in the name of progress.

During a 1997 BBC UK interview filmed on Banaba, King urged the governments involved in the mining of Banaba to act:

“We brought the Banabans into the modern world, and we cannot now turn our backs on them. Look at this island—it had some of the world’s leading technology. Let’s use technology again to rehabilitate this place and show the world what can be done. We must provide the Banabans with development, infrastructure, clean water, and the equipment they need.”

As an Australian citizen with direct familial ties to Banaba’s mining history, King believes she has the right to demand official recognition for the Banabans’ tremendous contribution and suffering in shaping Australia’s agricultural and economic success.

The Struggles of a Fourth World People

Under today’s political sphere, the Banabans are considered a “Fourth World People”—a displaced minority split between two Third World nations (Kiribati and Fiji). Political constraints have severely restricted aid and development projects for their two communities over the past decade.

Despite their resilience, the Banabans remain caught between history’s injustices and an uncertain future. Recognition and reparations from the nations that profited from Banaba’s destruction remain elusive.

The pressing question remains: where do the Banabans go from here?

_____________________________________________

Get the Books!

To learn more about Banaban history and their struggle to seek justice:

Te Rii ni Banaba: backbone of Banaba, Raobeia Ken Sigrah and Stacey M. King (2001: 2019)

Banaban Study Series:

Legacy of a Miner's Daughter: the impact of the Banabans after phosphate mining, Stacey M. King

Australia Banaba Relations: the price of shaping a nation, Stacey M.

Banaban Cultural Identity, Raobeia Ken Sigrah and Stacey M. King

____________________________________

For more information:

Come Meet the Banaban: https://www.banaban.com

Banaban Heritage Society: https://www.banaban.com/about

Banaban community Rabi, Fiji: https://www.banaban.com/banaban-community-rabi-today

____________________________________

About the Creator

Stacey King

Stacey King, a published Australian author and historian. Her writing focuses on her mission to build global awareness of the plight of the indigenous Banaban people and her achievements as a businesswoman, entrepreneur and philanthropist.

Comments (1)

This story shows how quickly a friendly game can turn ugly. It's crazy how the Banabans have faced so much over the years, from the Japanese occupation to these ongoing issues with their Fijian neighbors. Makes you wonder how they've held on to their identity. And what's this about their tenure on Rabi changing? That could be huge.