An unidentified female dynasty is revealed in a tomb with the biggest collection of beads in the world.

Ordinary shells, remarkable individuals

The Montelirio Tholos Tomb is a vaulted building located beneath the present-day town of Valencina de la Concepción in Southwestern Spain that has the remains of residents who lived there between 2875 and 2635 BCE.

According to recent findings, the seashell-stitched tomb sent a message about status, labour, and beliefs that were prevalent in a Copper Age civilisation already inclined towards social hierarchy throughout millennia.

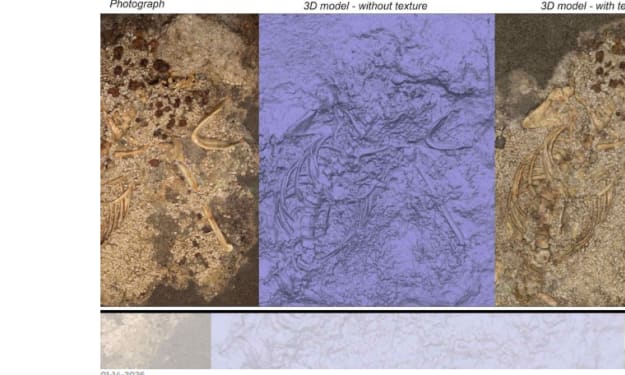

The bones, clothing, and decorations that this ancient culture was trying to communicate have finally been catalogued by archaeologists thanks to an interdisciplinary study.

On clothes that had once glistened like morning dew, they counted hundreds of thousands of tiny shell pearls, each less than a third of an inch wide. An economy capable of sustaining large-scale creativity is revealed by the overwhelming quantity of dazzling beads discovered in the Montelirio tomb.

The Montelirio tomb's women's chamber

A single chamber just 328 feet from the renowned grave known as the "Ivory Lady" was inspected by the study team, which was assembled from different Spanish universities and museums.

Twenty people's remains were found inside. Five are of unknown sex, while fifteen have been recognised as women. The real surprise—more than 270,000 shell beads that had formerly made complete tunics, skirts, and veils—was concealed by thin layers of dirt.

Separating those beads from dust took seven researchers 651 working hours, or almost three weeks of eight-hour days. The majority of the discs were made from Pecten maximus scallop shells that were gathered a few miles distant along the Atlantic shore.

Many surfaces still reflect light five millennia later, indicating that the clothing once shone green and white next to ivory, amber, and cinnabar pendants.

enormous and well-coordinated effort

It took a lot of time and calm hands to produce such a collection. A single disc takes about ten minutes to shape and drill, according to experimental reproductions.

At that rate, it would take ten expert craftspeople working eight-hour shifts 206 days in a row to complete the treasure uncovered in this single chamber. Nearly 2,200 pounds of raw shell had to be collected and transported ashore before any cutting could start.

These numbers reflect a society that can spare experts from farming for the majority of the year. Workers were nourished by food surpluses, deliveries were planned by organisers, and local officials determined that shimmering clothing was important enough to warrant the effort.

The Montelirio tomb's level of coordination is comparable to other significant Copper Age endeavours in Iberia, such as the long-distance ivory trade and the irrigated cultivation of emmer wheat.

Dating the deceased at the tomb of Montelirio

The clothing was probably constructed close to the time of burial, as evidenced by the tight clustering of radiocarbon dates from multiple beads and adjacent bones. The skeleton next to one anomalous bead appears to be older.

That one discrepancy raises two possibilities: either artisans made new garments every time the Montelirio tomb opens over the course of maybe thirty years, or a sudden crisis claimed many lives, leading to a desperate seven-month manufacturing rush prior to a communal burial.

Both choices need meticulous preparation and a common ritual schedule. Each was older than most of the others, in their mid-twenties to early thirties, and had the most intricate bead work.

One of them was lying face down, a peculiar stance that might indicate a specific spiritual role. When taken as a whole, these hints imply that the community centred funerary displays around seasoned female leaders.

Heavy beads with light linen

The discs were sewed onto a woven substrate, most likely made of linen, as evidenced by microscopic plant fibre traces on numerous beads. Replica clothing proved to be too heavy, stiff, and noisy to wear every day. Rather, the attire most likely only showed up at ceremonies.

Shell, pigment, and fabric were transformed into a moving billboard of power by such clothes, which allowed the wearer of two hundred pounds of clacking apparel to govern significantly more labour than a typical farmer.

Sea, society, symbolic reach: By standardising disc size and colour, Valencia producers may have created a medium of exchange that only high-ranking households could commission and redistribute. The bead work stitched that wealth directly to its owners' bodies.

Later Mediterranean cultures, including Greek and Roman, linked scallop imagery to myths of love and birth, themes that echo ideas of fertility and origin common in many prehistoric societies. In California, Chumash coastal groups circulated them hundreds of miles.

The metaphorical appeal of seashells probably resonated across cultures that were separated by time and language, even though Montelirio lived two millennia before those myths.

Gender roles are also highlighted by the clothing. Leadership in Valencia was not exclusive to men, as evidenced by the fifteen verified women in the chamber and the "Ivory Lady" standing close by.

High-status women shaped ceremonial life, commissioned luxury products, and managed resources. The idea that early European hierarchies were solely patriarchal is refuted by the predominance of women, which adds complexity to discussions of authority prior to the Bronze Age.

Ordinary shells, remarkable individuals

The Montelirio tomb treasure shows how commonplace things may become spectacular through teamwork, even though shell beads may seem insignificant in comparison to gold or jade.

A decision is recorded on each disc: collect a scallop, cut it, drill it, polish it, and attach it to a thread. When you multiply that decision by 270,000, the outcome is a societal statement made by an ancient community that has left its stamp on history.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.