3 Times Safety Rules Were Written After It Was Already Too Late

#1. Workplace Radiation Safety (The Radium Girls, 1910s–1920s)

Safety rules like to pretend they are proactive. They wear reflective vests, carry clipboards, and speak confidently about prevention. But history knows the truth: many safety rules were written after something went catastrophically wrong, when prevention was no longer an option and regret had already filled out the paperwork.

These rules are not born from imagination. They are born from disasters so shocking that society collectively paused, looked at the wreckage, and said, “Okay. We are never doing that again.”

In other words, safety regulations are often apology notes written in legal language.

Here are three times safety rules arrived late—very late—after the damage had already been done.

3. Factory Fire Exits (The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, 1911)

Before 1911, factory safety was less a concept and more a suggestion. Buildings were tall, crowded, flammable, and designed with one primary concern: efficiency. Workers were replaceable. Equipment was not.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City occupied the upper floors of a building filled with young garment workers—mostly immigrant women. To prevent theft and unauthorized breaks, factory owners kept doors locked during work hours. Fire escapes were flimsy. Safety drills were nonexistent.

On March 25, 1911, a fire broke out.

Within minutes, the upper floors were engulfed. Workers ran for exits and found doors locked. Fire escapes collapsed. Some women jumped from windows to escape the flames, choosing gravity over fire in front of horrified onlookers.

By the time the fire ended, 146 people were dead.

Only then did society react.

Fire safety codes were rewritten. Exit doors could no longer be locked. Buildings were required to have multiple exits. Fire drills became mandatory. Sprinkler systems became standard.

Of course, exits should be unlocked. Of course, buildings should allow escape. But until bodies piled up in the street, no one enforced what hindsight now considers common sense.

The rules saved millions later. They arrived for 146 people far too late.

2. Lifeboat Requirements (The Titanic, 1912)

Before the Titanic set sail, maritime safety rules were confidently outdated. Lifeboat requirements were based on a ship’s tonnage—not the number of passengers—because ships simply weren’t built that large before. Updating the rules would have required admitting the industry had outgrown its own assumptions.

The Titanic was marketed as nearly unsinkable. Carrying full lifeboat capacity would clutter decks and ruin aesthetics. Confidence replaced caution. The ship sailed with lifeboats for just over half the people on board.

When the Titanic struck the iceberg on April 14, 1912, the problem was not the collision—it was the aftermath.

Chaos followed. Lifeboats were launched half-empty. Passengers didn’t believe the ship would sink. Crew had never practiced a full evacuation. Safety rules had not accounted for human behavior, panic, or disbelief.

Over 1,500 people died in freezing water.

Only after the ocean had claimed them did regulations change.

International maritime law was rewritten. Ships were required to carry enough lifeboats for everyone. Continuous radio watches became mandatory. Ice patrols were established.

The ship became a floating classroom, teaching lessons no one aboard survived to apply.

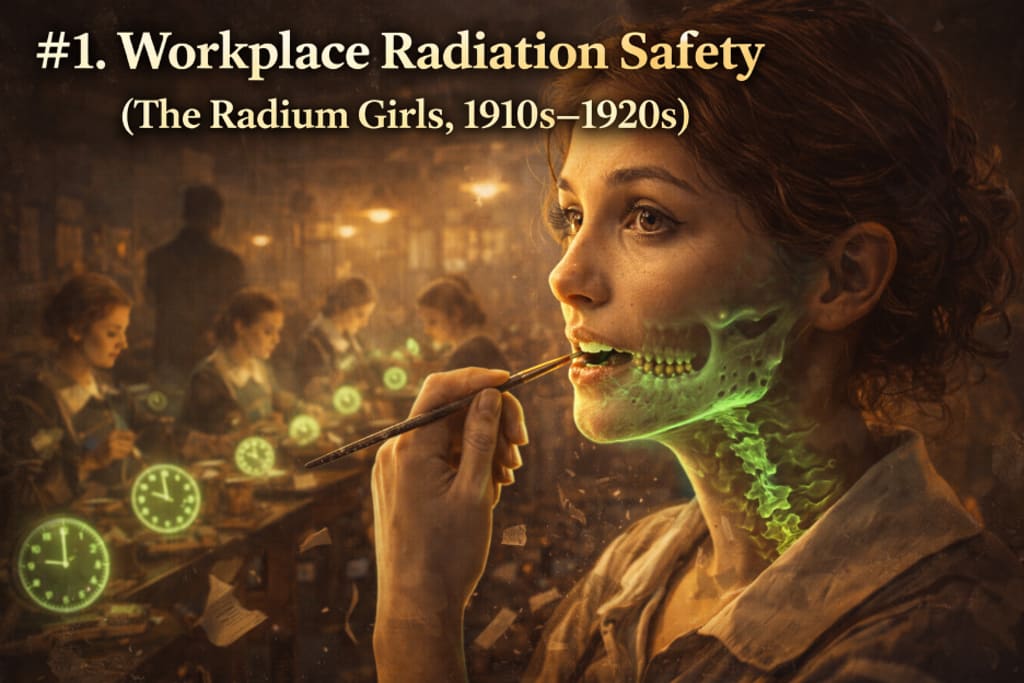

1. Workplace Radiation Safety (The Radium Girls, 1910s–1920s)

In the early 20th century, radium was a miracle substance. It glowed. It symbolized modernity. It was used in medicine, cosmetics, and most fatefully, watch dials.

Young women were hired to paint radium onto clock faces using fine brushes. To keep the brush tips sharp, they were instructed to lick them between strokes. Management assured them the substance was safe—some executives even claimed it was healthy.

The women glowed faintly in the dark. It was charming. It was fashionable. It was deadly.

Over time, the workers developed horrific symptoms. Teeth fell out. Jaws disintegrated. Bones became brittle and fractured easily. The radium had accumulated inside their bodies, slowly poisoning them from within.

The companies denied responsibility. Doctors were confused. There were no safety rules—because no one had bothered to imagine the risk.

Only after lawsuits, public outrage, and multiple deaths did radiation safety standards emerge. Protective equipment became mandatory. Exposure limits were established. The phrase “occupational hazard” gained real weight.

The rules saved future workers. They did nothing for the women who had already been told to smile, dip, and lick their brushes.

The unsettling part is how preventable it all was. The rule didn’t require advanced science—just basic caution. But caution arrived after the damage was irreversible.

Conclusion

Safety rules like to present themselves as guardians of the future, but many are better described as historians of catastrophe. They are written not to prevent the first disaster, but to prevent the next one.

What makes these stories so uncomfortable is how familiar the reasoning sounds:

● It’s never happened before.

● The risk is minimal.

● We’ll deal with it if it becomes a problem.

By the time it becomes a problem, it’s already too late.

Safety rules are paid for in advance by ignorance—and settled in full by loss. And while they do save countless lives later, they always arrive carrying the quiet weight of those they couldn’t save in time.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.