'To Be or Not to Be' (1942 vs. 1983): When Comedy Laughs in the Face of Fascism

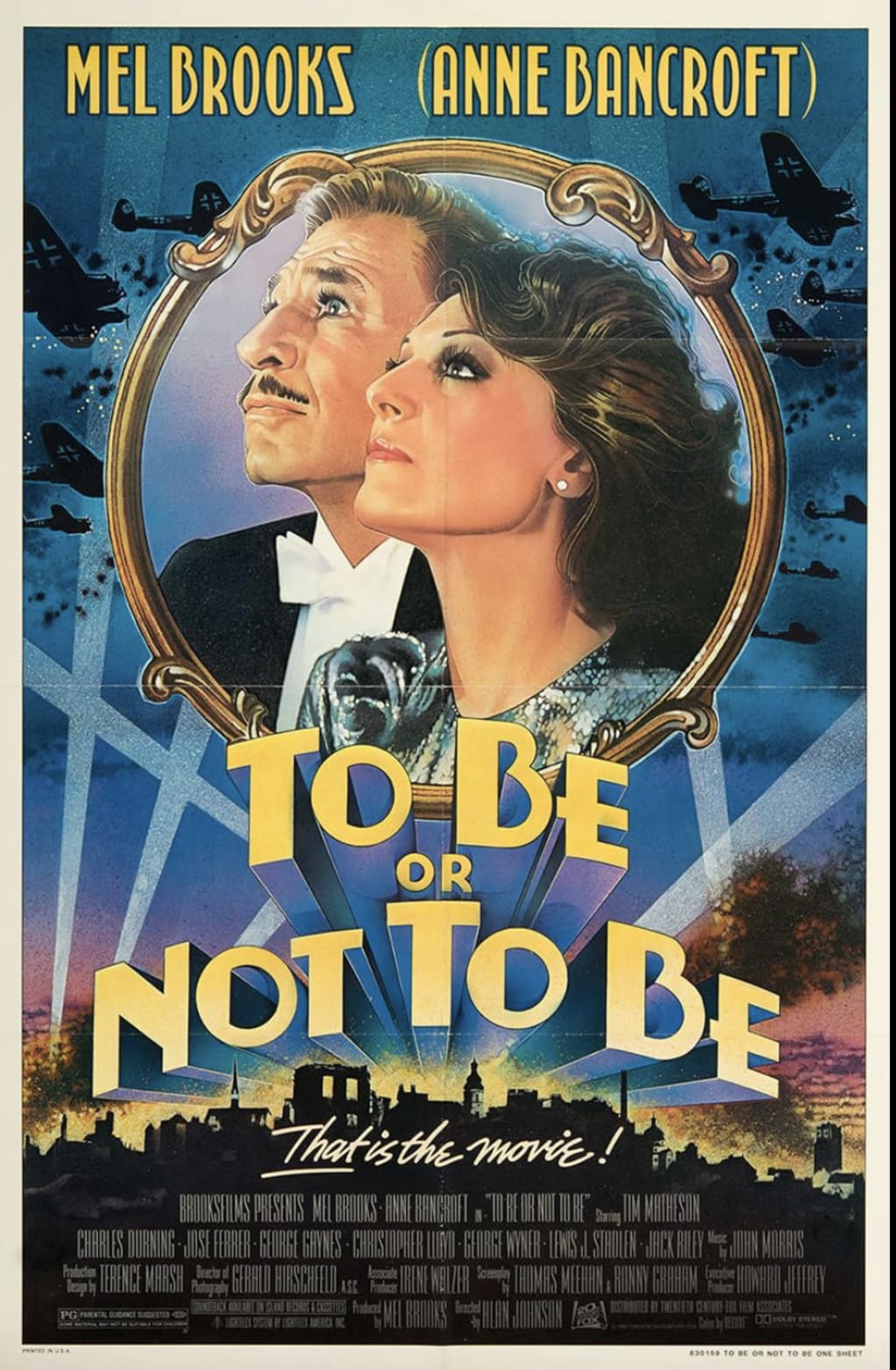

Mel Brooks Remade Ernst Lubitsch for the 1980s in To Be or Not to Be.

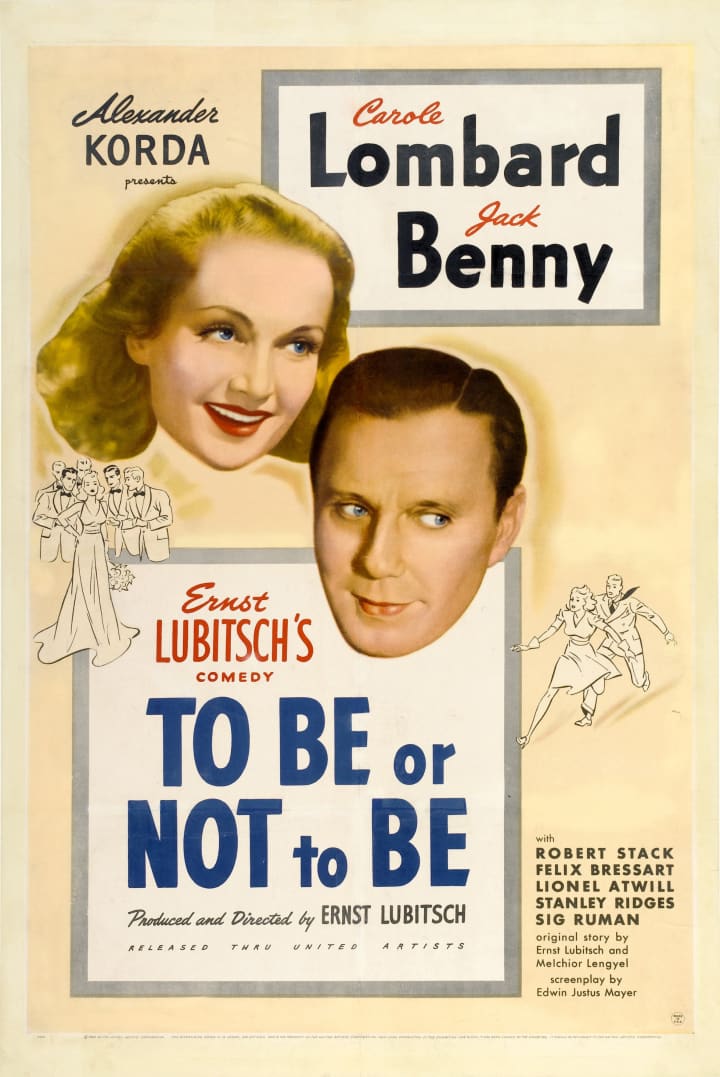

In 1942, Ernst Lubitsch released To Be or Not to Be into a world already at war with itself. The ink on the headlines was still wet. Europe was in flames. Hitler was not a punchline — he was a living, breathing catastrophe.

In 1983, Mel Brooks remade that same film for a very different audience. The war was now history. The wounds had scabbed over. Nazis had become villains in adventure movies, video games, and late-night jokes.

Same title. Same plot. Same central idea.

Two radically different acts of courage.

The Lubitsch Audacity (1942)

To call To Be or Not to Be (1942) “brave” almost undersells it.

Lubitsch made a comedy about Nazis while the Nazis were still winning.

The film centers on a troupe of Polish actors whose theatrical skills become their greatest weapon against occupying forces. It’s clever, romantic, and sharply funny — but it’s also dangerous in a way that modern audiences can easily miss.

At the time of its release:

• Poland had been crushed.

• Jewish audiences were already being erased.

• News from Europe was incomplete but horrifying.

And yet Lubitsch dared to do the unthinkable:

He made the Nazis ridiculous.

Not cartoonish. Not harmless. Ridiculous.

That distinction matters.

Jack Benny’s Josef Tura is vain, insecure, and deeply human. Carole Lombard’s Maria is clever, sexually confident, and fearless. The Germans, by contrast, are rigid, self-important, and trapped in their own absurdity. Power becomes their weakness.

Lubitsch understood something essential: tyranny depends on people believing in its seriousness. Once you laugh at it, it starts to crack.

The humor is elegant. Precise. Often delivered with a raised eyebrow rather than a punchline. This is the famous “Lubitsch touch” — humor that trusts the audience to keep up.

And beneath the wit is a quiet defiance.

Art — acting itself — becomes an act of resistance.

The Brooks Provocation (1983)

Mel Brooks’ To Be or Not to Be arrives forty years later, and it knows it.

This is not a remake trying to replace the original. It’s a remake in conversation with it — louder, broader, and more explicitly angry.

Where Lubitsch used elegance, Brooks uses volume.

Where Lubitsch hinted, Brooks shouts.

And that’s not a flaw — it’s the point.

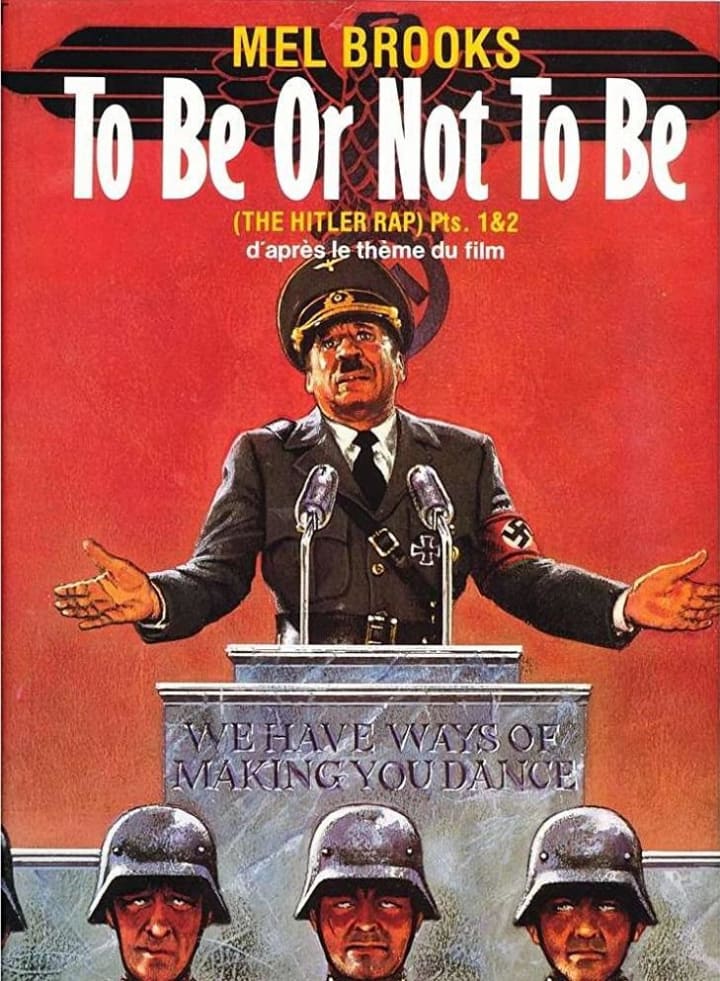

By 1983, Brooks had already built an entire comedic identity around mocking authoritarianism (The Producers, Blazing Saddles, History of the World, Part I). His Nazis aren’t just ridiculous — they are aggressively stupid, sexually insecure, and obsessed with power they don’t understand.

Anne Bancroft’s Maria is no longer simply clever — she’s openly confrontational. Brooks’ Josef Tura isn’t just vain; he’s a walking comic meltdown, fueled by ego and panic.

This version leans harder into:

• Sexual humor

• Verbal aggression

• Physical comedy

• Jewish identity as open defiance

Brooks doesn’t ask permission to laugh at Nazis. He demands it.

And in doing so, he reframes the story for a post-Holocaust, post-Vietnam, post-Watergate America — a country that no longer trusts authority and doesn’t feel obligated to be polite about it.

Same Story, Different Risks

What’s fascinating is that both films take enormous risks — just in different directions.

Lubitsch risked making light of a terror that had not yet revealed its full horror.

Brooks risked being accused of vulgarizing history that had already been sanctified.

Both understood that comedy isn’t about comfort.

It’s about confrontation.

The original whispers: They are not gods.

The remake yells: They never were.

Acting as Resistance

One idea survives both versions intact:

acting is survival.

Disguises, accents, timing, confidence — performance itself becomes a weapon. The actors defeat the occupiers not with guns, but with belief. If you sell the lie hard enough, authority collapses under its own assumptions.

That idea hits differently in each era.

In 1942, it’s a hopeful fantasy.

In 1983, it’s a cynical truth.

But in both cases, it’s deeply cinematic — a love letter to the power of performance.

Which One Wins?

That’s the wrong question.

Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be is a miracle of timing, taste, and courage — a film that shouldn’t exist, yet does.

Brooks’ To Be or Not to Be is a declaration — that comedy doesn’t owe history its silence.

Together, they form a rare cinematic dialogue across four decades, proving that laughter can be both elegant and obscene, quiet and furious — and still hit the same target.

Fascism hates being laughed at.

That alone makes both films necessary.

About the Creator

Movies of the 80s

We love the 1980s. Everything on this page is all about movies of the 1980s. Starting in 1980 and working our way the decade, we are preserving the stories and movies of the greatest decade, the 80s. https://www.youtube.com/@Moviesofthe80s

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.