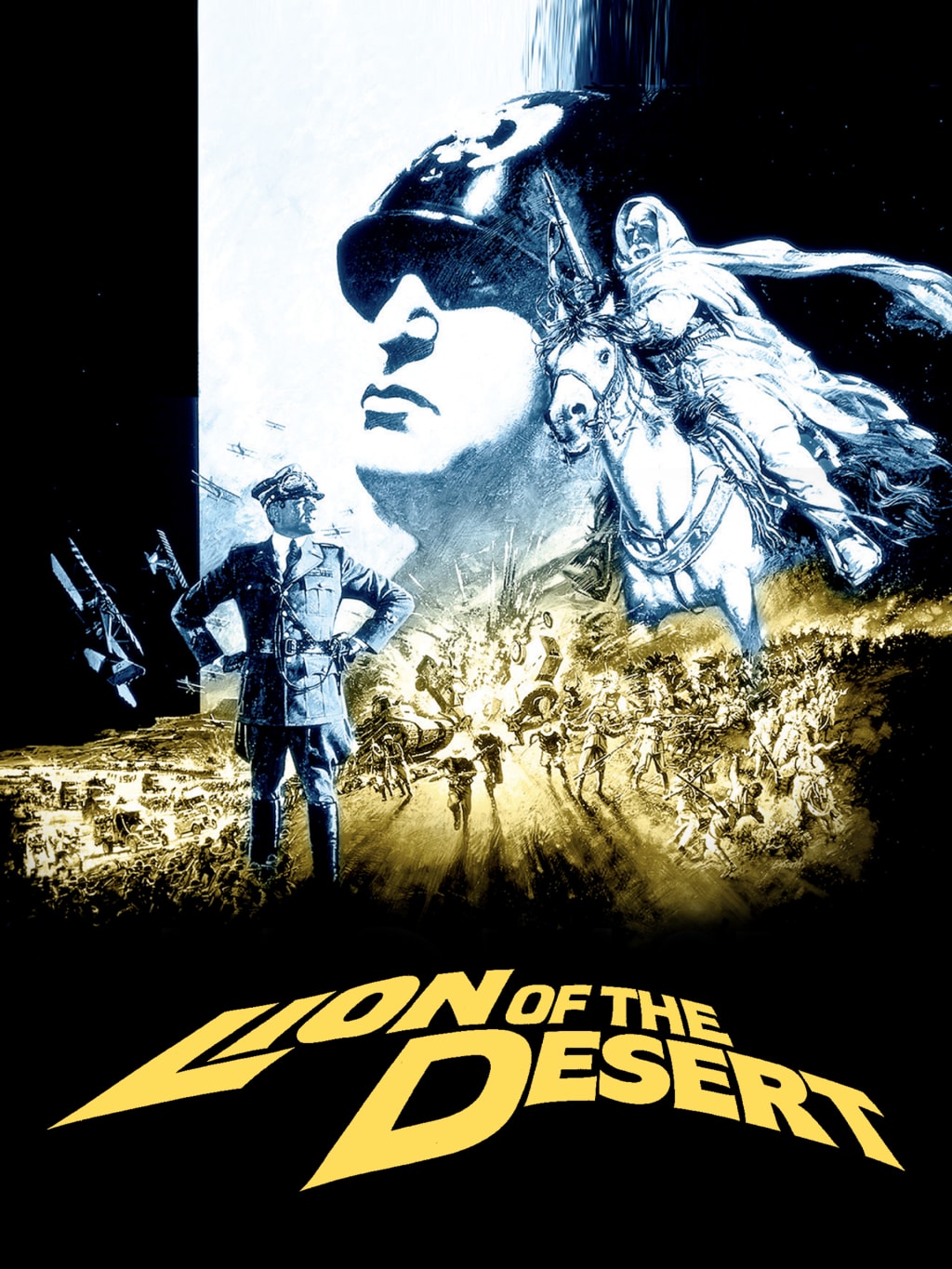

The Rise and Fall of Lion of the Desert: How an Epic Became a Box Office Tragedy

A deep look at Moustapha Akkad’s Lion of the Desert (1981), its $35 million budget, its political controversies, and how it became one of the most infamous box-office failures of the 1980s.

An Unlikely Hollywood Dreamer

In 1981, reporter Bob Thomas of the Associated Press wrote of filmmaker Moustapha Akkad, calling him “an improbable success story.” Akkad spent the first half of his life in Syria before falling in love with Hollywood movies. He went to UCLA, studied filmmaking, and used his Middle Eastern connections to make his feature debut, The Message, about the origins of Islam. The movie never played in the U.S. after a disastrous screening in Washington D.C.

That screening in 1976 was protested by Black Muslims to the point where the film could not be shown. The protest frightened away distributors and, despite a healthy budget to distribute the film independently, protests also came from the Arab world where Akkad hoped the film would find its strongest audience. Many in the Arab world believed that the film contained a depiction of the Prophet Muhammad, though the actual film does not.

It took a few years, but The Message eventually bounced back and eked out a profit, overcoming rumors and misinformation. Less than two years after being essentially shadow-banned, it began to play in Middle Eastern countries and found its footing.

In the middle of struggling to save The Message, Akkad stumbled into a brand-new level of success: he helped finance and produce John Carpenter’s low-budget horror film Halloween.

A Horror Hit Funds a Historical Epic

Halloween was released in 1978 and became, for a time, the highest-grossing independent film ever made. That success gave Akkad the resources and confidence to mount his next, far more ambitious film—the sweeping, historical epic Lion of the Desert. The film is based on the life of Omar Mukhtar, a venerated figure in Libyan history. Mukhtar defended his people against Italian fascist invaders, heroically losing his life in the fight.

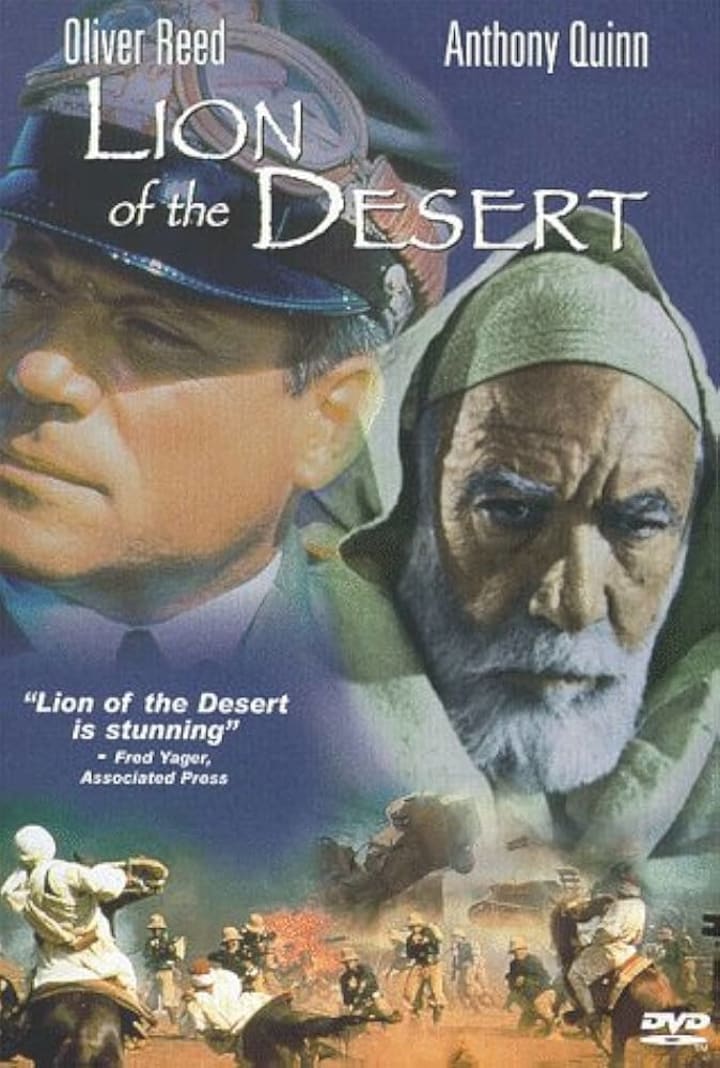

Akkad first got the idea of a Mukhtar movie when his friend, legendary actor Anthony Quinn, brought him a script he wanted to star in. Quinn believed, quite correctly, that Akkad’s Middle Eastern connections could secure financing for a film of the scale the story deserved. Instead of optioning Quinn’s script, Akkad became so excited that he wrote his own and began securing funding—with Quinn set to star as Omar Mukhtar.

Gaddafi’s Money and the Cost of Support

This is where the story turns. Though flush with cash from Halloween, Akkad sought outside financing for Lion of the Desert and knew exactly where to go. Traveling to Libya, he pitched the film to Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. The dictator was known for lavish spending, and Akkad secured a commitment of $35 million, a staggering sum for 1980.

Not only that—Gaddafi sent more than 5,000 Libyan soldiers, plus weapons and uniforms, to be used in the production. It was more support than Akkad could have imagined, but it came with immense complications.

The budget allowed Akkad to shoot in an actual desert, which sounds ideal until you consider how cameras and sand are natural enemies. Several times the production faced windstorms and equipment failure. Akkad was forced to innovate simply to keep sand out of the film canisters, using Gaddafi’s money to protect equipment and invent workarounds.

Meanwhile, the cast and crew lived lavishly behind the scenes—in a camp outfitted with air conditioning, an indoor pool, a movie theater, and an on-set restaurant, all courtesy of Gaddafi’s bottomless checkbook.

The International Politics That Sank the Film

But Gaddafi’s involvement also brought the film’s greatest challenge. Libya and Italy were locked in a longstanding political feud. Italian officials were already wary of a movie about a man who had famously resisted Italian fascism. They were deeply concerned about how the film would portray the Italian side of history.

It is odd considering history is unambiguous: Italy was the aggressor, and evidence overwhelmingly supports that Italian fascists committed atrocities, built concentration camps, and caused the deaths of more than 200,000 Libyans.

Nevertheless, Gaddafi’s reputation as a tyrant—combined with Italy’s discomfort with its own past—led Italian authorities to ban the release of Lion of the Desert. This was catastrophic. Italy in the late ’70s and early ’80s was the gateway to European distribution. Without Italy, the entire European market became nearly unreachable.

And then came the American problem.

In 1981, Gaddafi was emerging in U.S. media as a dangerous figure, aligned with Russia and openly aggressive toward neighboring Chad. To release a film funded by him at this moment was… problematic. Italian censorship only highlighted Gaddafi’s involvement, branding the film as propaganda. American audiences might not have known the full political story, but they knew enough to be cautious.

As a result, the film struggled to find any foothold in the American market.

Prestige Ambitions, Critical Praise, and Total Commercial Collapse

Despite the controversy, the film carried significant prestige. Anthony Quinn, Oliver Reed, and Rod Steiger brought Hollywood gravitas, and critics praised the film’s scope, scale, and cinematography. Some noted that characterization was thin outside of Mukhtar’s heroism, but the film’s production values were undeniable.

Akkad worked tirelessly to convince Italian authorities of its historical accuracy, but his efforts went nowhere. Lion of the Desert would not be screened publicly in Italy until 2009—and only on television.

The film held its first modest premiere in Spain in 1980 before making a strategic debut at the USA Film Festival in Dallas. There, on March 27, 1981, it screened for a private audience at $65 per ticket, including access to mingle with stars Anthony Quinn and Irene Papas.

That gala would be the film’s last moment of celebration. Its independent American release in April 1981 fizzled almost immediately. In total, Lion of the Desert made just $1 million, a catastrophic result against its $35 million budget.

There are few records of how Gaddafi reacted to the loss, though historians believe that simply having a film about a Libyan hero fulfilled his primary goal.

Akkad’s Abandoned Dreams

If Akkad endured any backlash from Gaddafi, history has not recorded it. What we do know is that Akkad abandoned the director’s chair after Lion of the Desert. He never directed another film despite long-held ambitions to create more Middle Eastern epics—films like Saladin and the Crusades or The Princess of Alhambra, based on the legend of the Tower of Princesses.

The failure of Lion of the Desert ended those ambitions. Akkad shifted his attention fully to the Halloween franchise, serving as Executive Producer on Halloween II and staying with the series through Halloween: Resurrection in 2002. He passed away in 2005.

A Noble Failure in the History of Epic Cinema

Lion of the Desert is a reminder that failure in Hollywood comes in many shapes. Some films are disasters from beginning to end—runaway budgets, egos, chaos. But some failures are noble, born not from greed but from ambition and conviction.

Lion of the Desert may be long, occasionally overwrought, and lacking the kinetic excitement of its clear influence, Lawrence of Arabia. But the scope, scale, cinematography, and performances are strong. And Akkad’s intentions went deeper than commerce—he was driven by passion, cultural connection, and a desire to honor Omar Al-Mukhtar.

Historians generally agree the film stays true to known facts: Mukhtar was heroic, Mussolini’s forces were the aggressors, and the atrocities depicted were grounded in reality.

Viewed this way, Lion of the Desert stands apart from infamous flops like Cleopatra or Heaven’s Gate. This was no tale of runaway spending or unchecked ego. This was a film crushed by politics, timing, and the collapse of European distribution—its fate sealed as much by Italy as by Gaddafi’s looming shadow.

And yet the film exists. That alone is miraculous.

The determination of Moustapha Akkad—who, for all the AP’s romanticism, truly did forge a unique American dream—brought Lion of the Desert into being. From Middle Eastern epic maker to unlikely horror-franchise steward, his journey remains remarkable.

Subscribe to Movies of the 80s here on Vocal and on our YouTube channel.

About the Creator

Movies of the 80s

We love the 1980s. Everything on this page is all about movies of the 1980s. Starting in 1980 and working our way the decade, we are preserving the stories and movies of the greatest decade, the 80s. https://www.youtube.com/@Moviesofthe80s

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.